On my Hike Across Great Britain in the summer of 2019, I hiked the Pennine Way. Much like the West Highland Way, it’s a popular and well-known trail that plenty of other people have written blog posts with details on what to take and how long to allow for.

What I want to do in this summary is talk about how I felt hiking the Pennine Way, what experiences I had, and interesting things that happened on my journey.

But first, a bit of background.

Descending the hills into Middleton-in-Teesdale.

What is the Pennine Way?

The Pennine Way is one of the UK’s longest named trails. It’s roughly 250 miles (400 km) – the full trail is longer but that includes several side-quests that would mean some doubling back if you took them. It’s also regarded as the toughest of all the long-distance paths in the UK. This is because it traverses the length of the mountainous ‘spine’ of England – the Pennines. Although called the Pennine Way, one end is in Derbyshire, in the Peak District, while the other is in Scotland, in the foothills of the Cheviots.

The Pennine Way has its reputation because of its tendency to go up and over mountains rather than round them. It’s also not a very direct route. This is because it’s a compilation of smaller footpaths connected together into one branded trail, designated to take into account the maximum amount of scenery rather than the most efficient route.

150,000 people hike at least part of the trail each year, while around 3,500 aim to hike the full path. Some try to do it all in one go, while many others do it in sections over a period of several weeks or months. It’s also usual to hike it South to North – this is largely because it’s best hiked in summer, and the long daylight hours means the sun is always behind you rather than in your face.

Is the Pennine Way easy to get to?

The two villages at the end of the Pennine Way are not particularly large. The southern end at Edale has a railway station to Manchester and Sheffield. Kirk Yetholm and nearby Town Yetholm, at the northern end, is a larger village but is a harder place to get to by public transport, requiring a change of buses in Kelso.

The signpost at the official start of the Pennine Way in Edale. Pic taken on an earlier different adventure. Still wet.

The Pennine Way connects with many other footpaths and trails along its length. At the southern end there’s a whole myriad of paths across the Peak District, while at the northern end it connects with the St Cuthbert’s Way from Melrose to Holy Island. In between one can take local named paths in places like Rochdale and Kirklees, or longer trails like the Coast to Coast path or the Hadrian’s Wall path. It also connects with the Yorkshire Three Peaks.

Both ends of the Pennine Way are at pubs. This probably shouldn’t come as a surprise. At Edale the pub is an old building, all very stone cobble, called ‘The Old Nags Head’. The Kirk Yetholm end is at a similarly old stone building called ‘The Border Hotel’, which has seating outside overlooking the village green. You can claim a half-pint of beer at either if you’ve completed the Pennine Way. When asked ‘but how do you prove it’, the bar staff at the Border Hotel said ‘oh, we can just tell’. Evidently hiking 16 days along England’s longest mountain range changes you in some way.

The Border Hotel in Kirk Yetholm.

What is the scenery like on the Pennine Way?

The scenery along the Pennine Way is very varied. The first few days the path goes through the Peak District which gets progressively more bleak the further north you get. If you can avoid getting lost on Kinder Scout, you go past the site of my first wild camp just outside Crowden, where you can look out over the first of the many reservoirs en route. From here you hit the Dark Peak, with pretty much nothing but steep hills, muddy paths, and the occasional stream to cross. You might look at a map of the route and guess the emptiest parts would be in the centre of the Pennines. You’d be mostly wrong.

A signpost somewhere on the Dark Peak. At least you know you’re going in the right direction.

After passing ’The Hills Of Hebden, Hell, and Halifax’ the scenery becomes largely agricultural – lots of cows and sheep, with winding country lanes and dry stone walling. Just after Malham you reach Malham Cove, a monstrous array of limestone paving that looks a bit like a mythical giant has been playing with Lego and then given up halfway. I was a bit wary of traversing them as the gaps between them do feel large enough to slip through and get stuck in – woe betide if you drop a phone down there.

The Limestone pavement at Malham. It looks better when you’re there.

As the trail gets higher the farmland continues but the fields get larger and just become seemingly endless hillsides of animals and shrubbery. These are punctuated by the occasional small village, waterfall, or trig point. Eventually you reach the Upper Tees Valley, and one of the most spectacular days en route. This starts in the town of Middleton-in-Teesdale, and follows the river for a few hours. It passes three waterfalls, each more spectacular than the last – Low Force, High Force, and Cauldron Snout. Indeed the latter requires scrambling up rocks by the side of it in a move that probably a couple of years previously I’d have had as a Hard Limit. The day ends nearly 21 miles later with a stunning vista at a place called High Cup Nick. You stand on top of a steep cliff looking down along a rounded valley towards the Lake District.

The valley at High Cup Nick. This also looks better when you’re there, but this said with a different vibe.

This part of England is part of the North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (the second largest into the country at 2,000 km²) and you can’t help but feel if it were anywhere else in the country, it would be filled with tourists. Yet we had it all pretty much to ourselves.

The waterfall at Cauldron Snout. Not pictured, but you can imagine, are the rock ‘steps’ we climbed up.

After following the wooded South Tyne Valley then the hills of Hadrian’s Wall, the path turns north again and ends up in logging country, with wide forestry commission roads passing through hectares of huge pine trees, some of which have been industrially chopped down leaving just areas of low stumps. It’s very easy walking territory, if slightly monotonous.

The last day or so of the Pennine Way, after Byrness, is over the Cheviot Hills – the bleak, undulating, and misty boundary between England and Scotland. The path crosses several times and follows the border here for much of its length, though there’s not much to see to mark it, just a farmer’s field fence. There is pretty much nothing here at all for about 20 miles, save some Roman ruins and a couple of small streams. The trail down the other side in the descent into Kirk Yetholm is much more green and the view is wider.

The summit of Great Shunner Fell. I am not aware of a Lesser Shunner Fell.

The Pennine Way climbs over several high mountains, including Cross Fell which, at 893m, is the highest point in England outside the Lake District. The path up is a steep climb near a road that goes to one of those mysterious golf balls the Ministry of Defence is quite fond of. Other high peaks include Great Shunner Fell, Windy Gyle in the Cheviots, and Pen-y-Gent in Yorkshire. The latter is one of the Yorkshire Three Peaks, three of the highest peaks in Yorkshire, and as it’s just beyond Malham, is one of the most popular and busy parts of the path. Despite the climb being pretty much a near-vertical scramble up narrow rocks. I am glad I didn’t have my heavy backpack that day.

The scenery on the Pennine Way is thus quite spectacular, if the weather was suitable for it. Reader, on my walk the weather was not suitable for it.

The summit of Pen-Y-Gent. I don’t know who took this pic but it was taken with Becky’s camera. All other electronic equipment was safely sealed away.

What is the weather like on the Pennine Way?

Not as much of the Pennine Way is open to the conditions as you might imagine, but when it is, it does feel quite hard. Our hike was during the middle of summer. You may remember the summer of 2019 being one of the hottest on record. Remember though it gets colder/cloudier the higher you go, and even though most of the Pennine Way was only in the 400-800m range, it was still Not As Summery As You Might Hope. Take a coat.

We’d checked the forecast before we started, and were expecting rain. It came just after our first lunch stop at Snake Pass, and stopped … well, the Wednesday afternoon was dry, as was most of the Friday, but the Saturday up Pen-Y-Gent was horrendous. It was only on the Sunday, seven days into the Pennine Way, that we had consistent comfortable and dry weather.

This led to two problems on the hike. The first was incessant rain had caused problems with the terrain, even after it had been dry a couple of days. Quite a bit of the trail was over boggy ground and at times the path itself disappeared into deep muddy puddles – indeed a couple of miles of trail just north of Tan Hill were so impassible that people coming the other way had told us to take a detour on the country lanes instead. In the Cheviots, my hiking partner Becky put a foot in a puddle and ended up sunk to her waist in mud. Slightly embarrassing.

The dangers of muddy footpaths. We’d just seen someone jog through this so Becky thought it was safe. Reader, it was not safe.

In addition, at one point in Northumberland I completely lost the path in a hillside of heather and marsh at least three times. This, coupled with my GPS going a bit awry, meant I ended up clambering to the top of a hill and throwing my hiking poles down in frustration and tears.

This was the other problem with the weather; the psychological effect. This hit me on the second and third days, when the rain was just torrential and everlasting. We were in the Dark Peak part of the path: open countryside and moorland, no shelter, no respite, with the wind blowing across the moors and the paths becoming invisible in the bracken and mud. The views were non-existent, and the whole setting just felt truly bleak. I wasn’t in the best of mindsets anyway given this was only a few days after ripping my toenail off so I was constantly worried about getting the wound damp and infected.

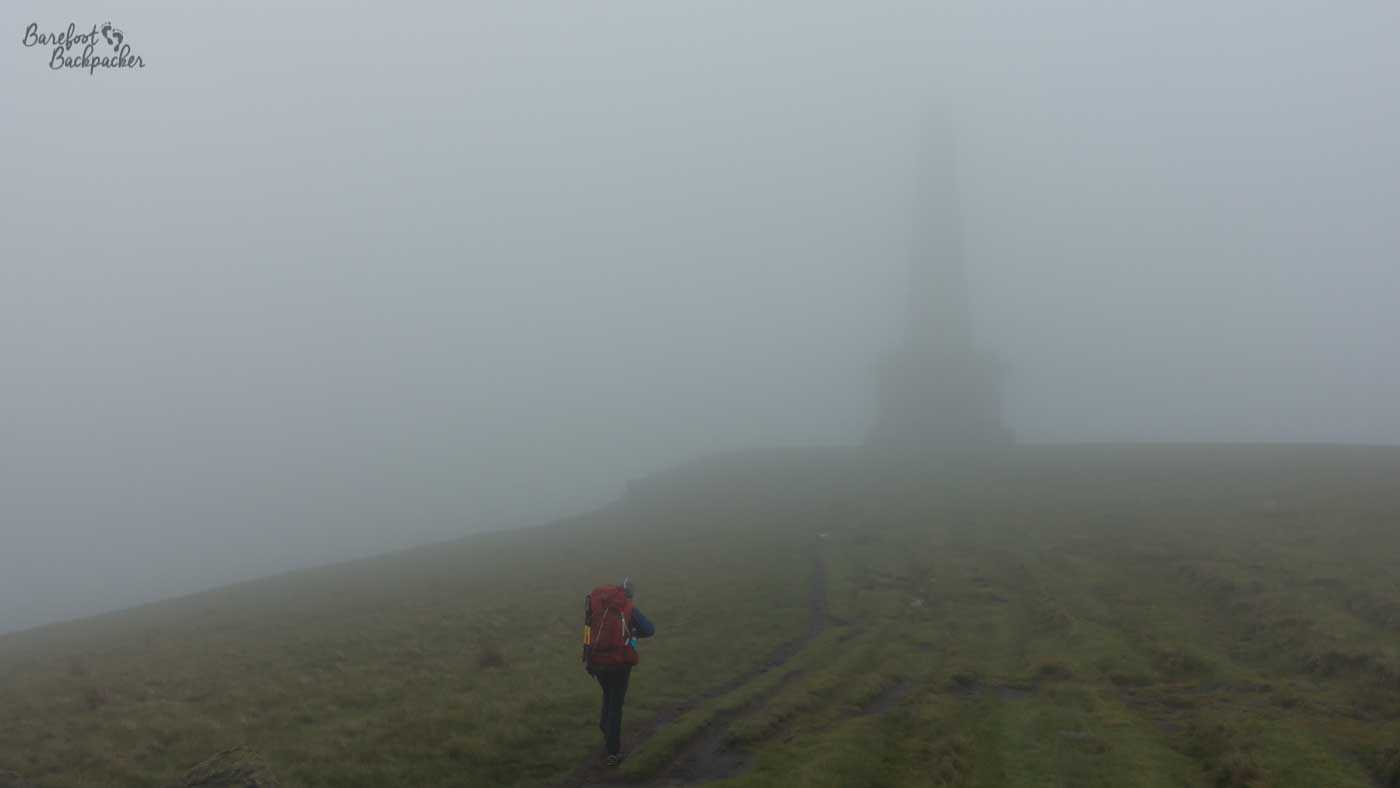

Even when it wasn’t raining it was still very misty and cloudy. Just south of Hebden Bridge in Yorkshire is Stoodley Pike. This is a hill on top of which is a monumental tower, about 120m tall, built to commemorate the British victory in the Napoleonic Wars. As we walked along the ridge from the south, over the grassy and bouldery moor, we kept seeing it in the distance. But no matter how far we walked, it never seemed to get closer, instead just disappearing into the cloud. Even when we got up close to it we could barely see it. You can go inside and climb a little way up it, but on our visit the views were …. not immense. We could just about see the base of the tower, to be honest.

Stoodley Pike is just visible. Honestly.

The second half of the hike was drier, and occasionally even sunny, but it was still more often than not grey and overcast. Conversely. though, it never felt too cold, barring the top of the fells – Cross Fell in particular was subject to winds so strong we could barely stand up straight, never mind keep warm by moving.

Weirdly, one of the nicest days weatherwise we had was the very last one. We’d overnighted in a bothy on the England-Scotland border, some seven miles from the end; we could barely see it through the fog and mist that was a constant companion in the Cheviots. But after descending a couple of hundred metres, we ended up having an absolutely gorgeous last few miles downhill into Kirk Yetholm – the skies cleared, the sun shined, the air was dry and warm – it was almost as if the Pennine Way was going, ‘Okay, I’ve thrown everything at you and you’re still here. Well done. You win.

Is there anything interesting to see along the Pennine Way?

The thing with the Pennine Way is it’s so long, there’s always going to be something interesting or odd to notice. Of course, some things are also temporary, and I certainly saw things on my adventure that were either unique to that time/place, or things our trip crossed over with. Obviously one is Hadrian’s Wall, but I’m not that sort of blogger.

We can’t go that way. This was a whole ‘nother incident that we won’t talk about.

For instance, strange as it may sound, we didn’t hike the entire length of the Pennine Way. Just south of Middleton-in-Teesdale, we were driven a short way in a small mini-bus because the bridge across Grassholme Reservoir was closed for filming some Hollywood war movie called ‘1917’.

Just south of there is Blackton Reservoir, and Hannah’s Meadows Nature Reserve. This is a small (7 hectare) Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) that is a rare example of a wild meadow with flowers and plants not often found elsewhere due to the nature of farming. The name comes from Hannah Hauxwell, a farmer who in the 70s and 80s became a small-scale celebrity due to being featured on her remote farm in a series of TV documentaries; an early example of ‘reality TV’.

The preserved railway station at Slaggyford.

I didn’t follow the path between Alston and Greenhead either. Instead, I (alone) took a detour along the South Tynedale Railway. This is a heritage steam railway that runs along the South Tyne Valley, as far as the wonderfully named restored station at Slaggyford. The route north of here is now a footpath which, given it’s flat, fairly straight, and runs through forest, is such a more viable alternative to the actual Pennine Way that runs close by, the guidebook we were using recommended it. The two finally diverge near Lambley Viaduct, a stone bridge some 260m long and over 30m above the river, and quite an impressive monument – even being designated a Grade II listed ‘building’. I carried on along the line to Haltwistle, then caught a bus west to Greenhead.

Posing for artwork, like the influencers we are.

On Wessenden Moor, just after the Pennine Way crosses the road to Holmfirth, there is a piece of artwork by Ashley Jackson designed for selfies. Called ‘Framing The Landscape’, it’s a huge wooden rectangular frame, and the idea is you use it to take pictures of yourself in the landscape with the frame acting as a, well, frame. Given the weather conditions, we didn’t linger long there but it’s an interesting thing too have out on the moors.

Somewhere in North Yorkshire, near Hawes, we were walking along a country lane the path was following, when we heard a horn from behind. Expecting to see a car, or possibly a farm vehicle, we instead saw a stylised old tractor, painted in bright colours. Followed by another one. And another one. It turns out this was an annual coast-to-coast rally / procession of vintage tractors, called the 3 Coasts Tractor Run – claimed to be the world’s longest annual tractor run, from Liverpool to Whitby and back. I’d say there must have been about 30-40 of them, all unique, all travelling slowly yet serenely.

The tractors on their way towards us. Each of them was painted/decorated differently.

Further south, the Pennine Way takes you past Top Withens, a ruined farm building in West Yorkshire, that is alleged to be the inspiration for the novel ‘Wuthering Heights’. Indeed only a couple of miles off-path is the hometown of the Bronte sisters, Haworth.

What remains of Top Withens. Ghosts not present.

Can you meet other hikers on the Pennine Way?

Given how many people hike the Pennine Way, and given it passes by several popular hotspots like Top Withens, means that it’s very easy to meet other hikers and even daytrippers.

Several of the people we hiked in conjunction with – these are The Americans.

Obviously there are large sections of the route where you might meet no-one at all (the Dark Peak, some of the more remote sections midway, and the Cheviots), but overall it’s rare to go a few miles without bumping into someone. Obviously this is easier to do walking southbound, since the majority of people hiking will be going north.

The nature of the Pennine Way, with standard ‘day-length’ sections, means it’s quite easy to end up walking in conjunction with other hikers. I don’t mean you’ll be walking with them all day every day, as you’ll all be going at your own pace, but if you’re mostly all going in the same direction and finishing the day in a similar place, you’ll keep bumping into the same people as you go along. For those of you doing the full hike, the number might lessen towards the end as people drop out, but certainly in the early stages you’ll probably be walking close to someone, or keep overtaking each other as you stop to lunch or take photos.

On my hike, we ended up hiking in parallel with quite a few other people, including a group of four retired but incredibly fit Americans. In the end we did the second half of the trail more or less constantly with two solo hikers, both called Simon. And because everyone understands that we’re all doing our own hikes in our own way, everyone knows you’re not obliged to spend the whole day with someone else, even if you’re pretty much going at the same pace, so you can be as sociable or as introvert as you need.

The bothy we overnighted in on our last night. This is Becky and The Two Simons.

One of the useful things though with hiking close by other people, especially given the weather conditions, is it means you can keep each other informed as to your progress, and to highlight issues with the trail. So if one of you discovers the path is unclear, they can send a message back to people behind saying things like ‘when you get to this point, head towards the hill with the cairn on top’, or warn of fallen or obstructive trees.

And of course it can get pretty lonely on those hilltops. #Subtweet.

Where do you stay on the Pennine Way?

The Pennine Way passes close to or through several small towns, so finding accommodation and places to stay shouldn’t be too troublesome most of the time. Indeed many guidebooks and websites suggest ‘days’ that start and finish in convenient places. Indeed the Americans were doing exactly that – having their luggage transported by road each morning leaving them purely to enjoy the hike. They were only carrying daypacks and knew there was a nice bed waiting for them at the end.

The hut we stayed in on our first night, in Crowden. The campsite at Byrness on our last night had similar but less pretty ones.

Our hike lasted 16 nights. For me this involved:

* camping at a campsite four times (my hiking buddy Becky did two more than me)

* wild-camping once (in an old sheepfold full of midges somewhere between Hadrian’s Wall and Bellingham)

* using dorms or chalets at campsites three times (two of these in the first four days, because of weather)

* staying in pubs/B&Bs three times

* Four nights in people’s homes

* one night (the very last one) in a bothy

We had intended to wild camp more, but we kind of just ended up in a routine of hiking along with the others and going from town to town.

The pubs/B&Bs I stayed in – the first was in Diggle in day two because the rain was so torrential, we felt we deserved a bit of dryness. As an aside, there used to be a pub and campsite where the Pennine Way meets the road to Diggle, but it had all closed a couple of years prior to our doing the hike.

One of the pubs we passed by – this was in Hawes. I overnighted in here here.

The other times I overnighted in a pub/B&B were in Hawes on the first Sunday – because I’d arranged to meet up with a local Twitter friend in the pub that evening so it made sense to stay the night – and towards the end of the hike in Bellingham, which was more for mental health reasons to be honest. These two days Becky slept in a nearby campsite.

Our campsites, whether in tents or chalets, were at Crowden, Ickornshaw, Tan Hill, Middleton, Alston, Greenhead, and Byrness. Special mention must be made to the site at Alston, which had the weirdest and creepiest toilet block I’ve ever encountered on my travels. It felt like for all the world like an abandoned nuclear bunker. Ickornshaw was, I believe, where we first met the Americans we’d end up hiking close with for the next week or so, in a campsite run by a chap who kept feeding us beer. And Tan Hill was the windiest place we overnighted; it’s allegedly the highest pub in England and has a space next to it you can ‘wild camp’. Setting up the tents was quite a tough affair, as you can imagine, But at least it was dry. The pub has a reputation in Winter – a couple of times in the last decade people have been trapped inside it for several days because of snow.

The Tan Hill Inn. We camped outside, in the space behind the tractor, in front of the rocky escarpment at the back of the pub.

We also passed a few other places where it would be possible to overnight in relative comfort (ie, not get wet). For example, there’s a hut on the descent from Cross Hill, and there’s a setup a short distance south of Hannah’s Meadows with two floors, a kettle, and even an actual bed; we stopped there for lunch.

A special mention needs to be made for our very last night. At this point four of us (me, Becky, and the two Simons) were hiking together pretty much constantly, and we’d made it to the misty Cheviots. It was getting fairly late, and cold, but we knew on the map there was a bothy (a stone hut) just past the turn-off for The Cheviot. We made it there quite late, and found it was occupied by two people. Not hikers, but, of all the bizarre things, race marshalls, with watches, clipboards, and an extraordinary amount of tea and biscuits.

This was admin for the Spine Race, a twice-yearly ultramarathon along the entire Pennine Way from Edale to Kirk Yetholm, taking exactly the same path as us. But instead of hiking it leisurely, they run it. The 2019 summer Spine Race attracted 40 hardy competitors, of whom 27 finished – the winner (Sabrina Verjee, who finished in 81 hours and 19 minutes, and had slept about three and a half of them) passed us earlier in the Cheviots looking like she was out doing a casual Parkrun.

It’s nice that people feel the need to challenge themselves in different ways, and it’s really good to appreciate that. Still wouldn’t do it, mind.

Can you hike the Pennine Way barefoot?

There are certainly large sections of the Pennine Way you can hike barefoot. As long as you’re comfortable with a bit of scrambling, pretty much the whole of the Peak District section in the first few days is over either paths with big stones, or grass/mud trails. Some parts are laid with large flagstones too, both in the Peaks and the Cheviots, so that would help, and of course the short limestone pavement section at Malham Cove is made for barefoot hopping.

Better than sandals. I’d’ve had no chance in sandals. Honestly even surviving with my boots would have been 50-50. And I hate walking barefoot in mud.

Other bits though are less than ideal. There’s a few narrow very stony paths in the farmland section, some quite rough and rocky farm roads to navigate, and some of the descents in the higher mountains are covered with scree. Be aware too the trail is likely to be very muddy in places, especially in the Peaks and the section in Northumberland; YMMV on that.

In general though, in the moors, it felt a pleasure to bounce along happily barefooted like some kind of stereotypical elven ranger.

I *say* happily. This may have been my seventh attempt at this shot; I was already an hour and a half behind the main party, and had got lost once to this point.

Conclusion

The Pennine Way is one of the most interesting but also toughest hikes in the UK. It takes you through parts of the country you might look at on a map and go ‘yeh, that might be cool to take a day trip by car to’, and then not because the Lake District or the North York Moors are ‘just there’. But it goes through some spectacular scenery and interesting places. In addition, the sense of achievement from having done such a hike can never be beaten – the Pennine Way is a bloody hard and strenuous hike, and that I completed it with merely a few gripes to the weather, and with never any thought that I’d fail, is something no-one can ever take away from me.

In addition, I’d argue that many people don’t explore their own country enough – they’ll go flying around the world to see something interesting but don’t necessarily realise something equally as worthy lies on their own doorstep. So maybe if more people do hikes like the Pennine Way – and reminder you don’t have to do it all at once, you can do it in stages and it still counts – we can help to change that perception.

Writing this post has made me want to do it again.

Outside the Border Hotel at Kirk Yetholm is a place where people have left their worn-out walking boots, as a memorial to having completed the Pennine Way. My walking shoes were very falling apart and I left them here. Baby Ian & Dave couldn’t help but wave them goodbye too.