When people think of beer, they automatically think of Germany, and rave about the qualities of German beer. I’ll be honest, I’m someone used to the variety of craft beers, and in addition I think my problem is that a lot of German beer is traditionally lager-based rather than, say, IPA or porter or whatever, and I’ve never been overly fond of lagers. But as an avid beer drinker, it would be remiss of me to ignore the influence Germany has had over the world of beer, especially as beer has been brewed in what is now Germany for at least three millennia.

Schneider Weisse Aventinus. From Kelheim, in Bavaria.

But no discussion can ever be had without context. And in the case of German beer, that context is the German Beer Purity Law, or Rheinheitsgebot.

What is the Rheinheitsgebot? Why does the Rheinheitsgebot matter?

The Rheinheitsgebot is a law in Germany regarding the purity of beer, originally specifying the only ingredients that can be added to make beer in the country are water, barley, and hops. [Interestingly it didn’t specify yeast; the law was drafted before the exact science around brewing was definitively known]. It has been expanded and relaxed since, but only slightly. Now, it might come as a surprise to read that water was specified, as one might assume that was a ‘given’. While I find it hard to believe that anyone was seriously trying to make beer out of, say, milk in the middle ages, it does limit the German’s attempts to make a milkshake IPA, especially one made with blueberries or mango.

A Milkshake IPA from Neon Raptor, based in Nottingham UK. Contains Passionfruit, Mango, Vanilla, and Lactose; definitely not allowed in Germany!

There is some mis-knowledge about the Rheinheitsgebot, so here’s a very potted history. It was originally drafted up as long ago as 1516 – thus pre-dating the concept of ‘Germany’ by over 350 years. In those days Germany as an entity didn’t exist; the area was largely made up of a confederation of independent states collected together under the banner of the Holy Roman Empire, famously the most badly-named country to have ever existed. [And you thought ’Democratic People’s Republic’ was spurious!]. The Rheinheitsgebot was only implemented in one of these states, the albeit quite large country known as Bavaria, and the main reason wasn’t really around purity and standardisation of beer itself, that was more of the secondary aim. Rather the original law sought to regulate the usage of grains; ensuring brewers kept to barley and bakers kept to wheat and rye. In fairness, some brewers were putting some strange stuff in their beer; there were reports of substances like wormwood (commonly found in Absinthe and which causes, er, ‘interesting effects’ by all accounts) and belladonna, which, let’s face it, is not something you want to be consuming a lot of.

Although only applicable originally to Bavaria, it ‘spread’ across the rest of the Confederation, and upon German Unification in 1871, became a ‘law’ (although full adoption didn’t occur for another 40 years). This was mainly at the agitation of the Bavarian state who, let’s face it, were such a large enough entity in the new German country that they couldn’t be ignored. The law is still in place, although it only applies to German beer (not imported beer), nor does it apply to things like gluten-free beer. The ingredient list has been expanded (to now include any kind of malted barley) It also no longer prevents domestic brewers making beer outside of the provisions of this law, it just prevents them calling it ‘beer’.

A bottle of Dunkel beer from Landwehr-Brau. The note at the bottom of the label tells you it was brewed after the Rheinheitsgebot law was enforced.

In a way, the Rheinheitsgebot defines German beer in exact opposition to beer in the USA where, having suffered from prohibition and the restriction of home brewing until (my) living memory, there feels a lot more freedom; the vibe I’ve always had the impression of is ‘ah, stick it in and we’ll see if it works’. This makes American beer more varied (and some might argue more interesting) but German beer should be, on average, a better ‘quality’ since the ingredients and processes are more controlled and understood. This of course doesn’t always apply, in either direction; some American beers are absolutely fabulous, others you drink it and go ‘why on earth did you put that in?’. In Germany the differences are more to do with the skill of the brewer; it’s far too easy to make bad beer in the same way that 100 people making the same cake with the same ingredients to the same recipe will make 100 different cakes, not all of which will be edible.

Why is most German beer actually lager?

Traditionally, most German beer has been lager because that was the style of beer most commonly brewed by brewers in Bavaria when the Rheinheitsgebot was implemented, and with the protection that provided, they never really saw the need to change.

In fact, the Rheinheitsgebot only applied strictly to ‘bottom-fermented’ beer. This is old terminology based on where the yeasts sat when brewing; these days the terms are ‘cold-fermenting’ (bottom) versus ‘warm-fermenting’ (top). While the nature of brewing is beyond the scope of this blog (and beyond the scope of this blogger, let’s be honest; the smell of hops to me smells exactly the smell of cannabis, so while I have made my own beer, it’s possible you might not want to taste it. Although there’s a brewery in Andorra which brews beer with hemp, so ymmv), the most obvious effect is one of time: in ‘warm-fermented’ beers, fermentation is pretty quick (a couple of weeks), while for ‘cold-fermented’ beers the yeast ferments over a much longer period (often several months). In casual parlance, ‘cold-fermented’ beers are called ‘lagers’, while ‘warm-fermented’ ones are ‘ales’. Since the majority of beers brewed in Bavaria were already lagers, this was never an issue; the law regulated what they were already doing.

Ayinger Altbarisch Dunkel. From Aying, in Bavaria.

While the Rheinheitsgebot affected what was allowed to be brewed, there was another historical factor too. One of the problems with Bavarian beer at the time was the beer brewed during the summer months, and which was generally therefore ‘warm-fermented’, tended to go off quickly and end up tasting bad. To prevent this, in 1553, Duke Albrecht V banned brewing between late April and late September, Though this regulation was rescinded in 1850, that still meant the brewers of Bavaria had had 300 years of almost exclusively brewing with lager-yeasts and, in their eyes, why change a winning formula? And since Bavaria was the foremost brewing area in Central Europe, lager became the predominant form of beer in the whole region.

Why are there so many breweries in Bavaria?

Brewing in Bavaria seems to have been conducted for millennia. Indeed the oldest evidence for brewing in Europe in the archaeological record is a big pot with a flavoured form of weissbier, found in the grave of a Celtic chieftain near Kulmbach is what is now northern Bavaria, in around 800 BC. This makes Bavarian (German) beer older than Rome, which is quite a legacy.

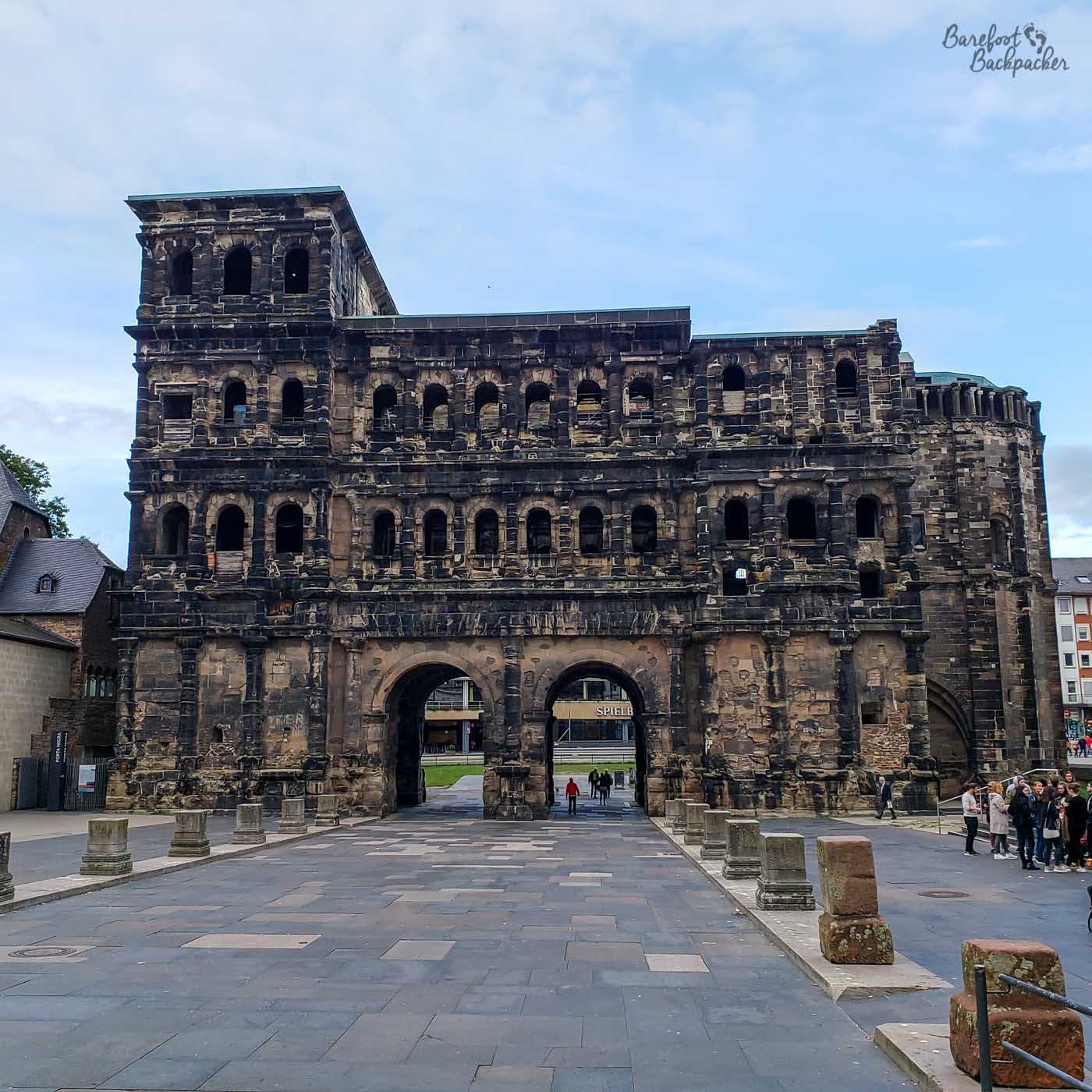

Brewing seems to have become, and remained, a mainstay of the Germanic tribes, and both their foes and their descendants. There’s evidence, for example, of the Roman Empire taking to brewing when they occupied part of the area around Regensburg – this, remember, is a civilisation more noted for its reliance on wine.

The Roman gate of Porta Nigra, in Trier, in western Germany.

As to why Bavaria specifically, it may partly be because the climate and agriculture favours the growth of barley and other flavourings. It’s interesting to note that while beer didn’t originally have to be made with hops, the first recorded incidence of hops being used for beer was in the 8th century, in what is now south-central Bavaria. The region (Hallertau) is reported to grow just over a quarter (26.66%) of the entire world hop crop.

Another aspect is religious. Bavaria is home to a large number of monasteries, and, just like the famous ones in Belgium, monks have been brewing beer for over a thousand years. Indeed two breweries that claim to be the worlds oldest continuously operating ones are both Bavarian monasteries: at Weihenstephan and Weltenburg.

Entrance to the Barfusser brewpub in Nuremberg – representing one denomination of monks who operated barefoot and brewed beer.

And you might well ask – why are monks noted for producing beer across Europe? Well, it’s a twofold reason. Firstly, daily monkish life wasn’t all prayer and sleep. Much of their daytime would have been spent gardening, for want of a better word. Remember monasteries would have been largely self-sufficient affairs so they consumed what they grew, So it makes sense that, with lots of free time in an enclosed space, they would have taken to experimentation and making use of what was available in a variety of ways, if only to make their mealtimes more exciting. Secondly, remember that one of the duties of a monk was to give back to the community, so much of the excess of what they grew, what they made, would have been traded in the local area. So monks brewed beer to drink themselves or sell, but they also produced lots of other consumables, like cheese, bread, and clothing

What styles of beer are produced in Germany?

Despite the restrictions imposed by the Rheinheitsgebot, there are a surprising number of variants produced, and a detailed breakdown of all the different styles of lager produced in Germany is beyond the scope of this blog post. In addition, I certainly can’t say that I’ve tried them all. However, there’s a few notable ones that should be mentioned.

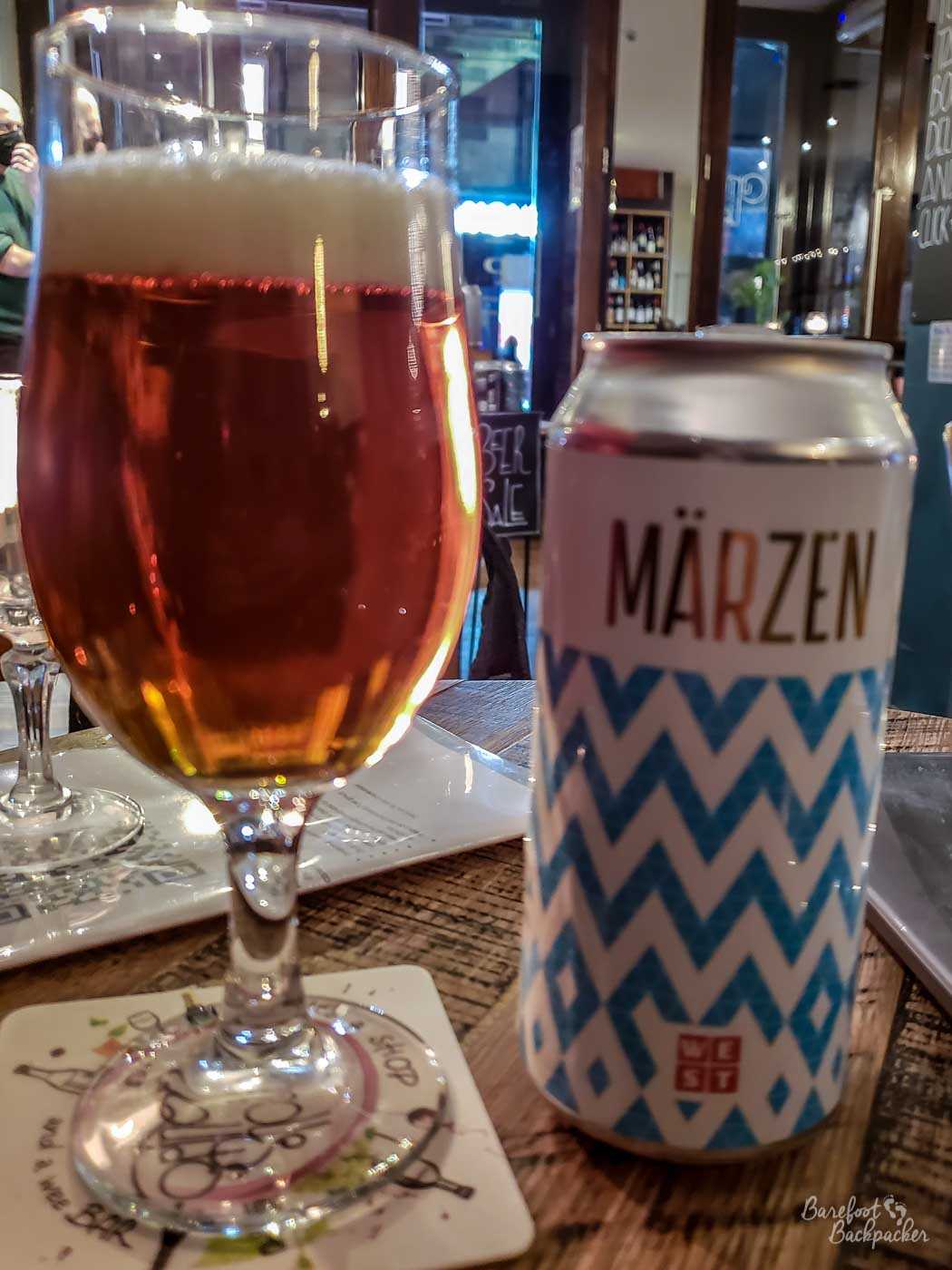

Marzen, from West Brewery. Although based in Glasgow UK, their remit is to produce beers that all align to the Rheinheitsgebot.

One of the most famous is Marzen. The name comes from the German for ‘March’ – the month it’s traditionally brewed – and was generally the last beer brewed before the annual shutdown decreed by Duke Albrecht V. It tends to be more hoppy, malty, and stronger (in the 5-6% range) – this is all so that it was able to be kept fresher while being stored over the summer. While not the style that springs most to mind when thinking of German beer, it should – it’s the traditional beer served at Oktoberfest. Incidentally, that Oktoberfest takes place just after brewing was allowed after the summer, that’s purely coincidental; the original Oktoberfest was in fact a royal wedding celebration in 1810.

The most common style though is Pilsener. It barely needs an introduction. It’s what people immediately associate when they think of German lager. What is interesting though is firstly, although first brewed by a Bavarian, the origins of the beer are actually in Plzen, in neighbouring Bohemia (and now part of Czechia), and secondly, it’s quite young a style compared with others, only being first produced in the 1840s. There’s a few sub-styles, but in general it’s a pale lager, around 4.5%, and … it exists.

Other light lager styles include Helles, Kolsch (which is a rare non-non-Bavarian style, coming specifically from Koln in the western part of Germany), and Malbock, another beer brewed in the springtime but made even stronger (up to 7%).

Dark larger styles exist. These are made with different, darker, malts that impart their colour into the final product. They tend to be more strongly alcoholic, and more full in flavour. And, let’s me honest, these are the ones I tend to prefer. The most common is ‘Bock’, which was originally brewed in Saxony. The name means ‘goat’, but is reputed to be called that as a result of the Bavarian accent mishearing the beer’s origins (a town called Einbeck) for comedic effect. It’s sweet, clear, strong (up to 7.5%), and pretty easy to drink. There is also Doppelbock which is the same but ‘more’ – darker, sweeter, and much stronger. – here we may even reach into double figure strengths. This is not a style to be downed-in-one.

An example of a Rauchbier, from Bavaria.

One possibly lesser-known style is Rauchbier. The name means ‘smoked beer’ and comes from literal smoke being used in production. When making beer, the barley malt needs to be dried. Usually these days this will be done in an oven; the temperature and length changing the colour and the taste of the malt produced. In more ancient times the barley may simply be left to dry in the sunshine. However, for Rauchbier, the malt is dried over an open flame, similar to how smoked fish is produced. The smell of the smoke (and presumably the wood used to start the fire) flavours the barley to produce a smokey-tasting malt. What you end up with is a beer that tastes faintly of smoked pork sausage.

Against the grain, one might say, is a completely different style of beer – Weissbier.

What is Weissbier?

Weissbier, or ‘white beer’, is beer brewed with wheat rather than barley. You may notice this contravenes the Rheinheitsgebot. But it’s defined as a ‘top-fermenting’ beer so it has an exception. You just have to use the right yeasts. Its name derives from ‘wheat’, because wheat is white, compared with most barley malts that are brown, but that doesn’t mean you can’t get darker-coloured variations of it.

An example of a Weissbier, from Bavaria.

Weissbier is traditionally very common in Bavaria, because of course it is. It has a very different vibe to other German beers, being softer, more ephemeral when drinking it, sweeter, and, most bizarrely, having an overall sense of banana. Of course there’s no banana In it – that would be a strict violation of Rheinheitsgebot (!) – rather the banana taste comes from the types of yeasts used, which given the laws around beer production may explain why it’s bigger in Germany than almost everywhere else; other nation’s brewers simply wouldn’t need to brew beer this way. It’s a beer style that takes some getting used to, but it’s worth trying.

[I say ‘almost’ everywhere else; it goes without saying that Belgium, and to an extent Netherlands, is exempt since they do pretty much everything]

Is there much craft beer in Germany?

The Rheinheitsgebot regulations tend to prevent many craft beers, as we would know them in countries like the UK and the USA; although there’s 1,300 breweries, and many of them are quite small, they mostly do variations on the same old themes. And you thought CAMRA were restrictive.

There are craft beer bars, but imported craft beers tend to be the ones on offer rather than domestic ones. Like Northern Monk. It was always Northern Monk. On my inter-rail trip as a whole I found that British brewer all over western Europe, including in Rennes and Bologna.

The “Craft Bier Bar”, am Wall, Bremen.

That’s not to say craft breweries don’t exist, although perhaps unsurprisingly you’re more likely to find they operate out of multi-cultural Berlin or the more casual north, rather than beer-heavy Munich. I’ve had a few domestic craft beers in bars in Bremen and Leipzig, for instance, including a porter from Landing Brewery (Hamburg), a couple of IPAs (one from Sudden Death Brewery in Lubeck, another from Brlo Brewery from Berlin), and a milk stout from Wittorfer Brewery in Neumunster, near the Danish border. They just take a bit more finding.

Conclusion

Beer is such a subjective taste. In researching this blog post I’ve had to drink quite a few different styles from different breweries; such a hardship I know. But obviously there’s a huge number I’ve not had the pleasure of sampling yet too – I only have Level 6 on Untappd for German beers.

Is German beer the best beer? I’d suggest if you like lager-style beers, German beer is definitely a strong contender for the best beer, but the Rheinheitsgebot regulations largely prevent many of my preferred beer styles from having much impact. In truth tho, if you’ve been making a certain kind of beer for over three thousand years, you’re going to be pretty good at it, so why change?

Prost!

Two of the beers from Barfusser brewery, Nuremberg.