I always wonder about the pre-Roman peoples of Western Europe. Looking through the lens of a 21st century human, I always wondered why so many of these ancient civilisations decided to base themselves on the very edge of the land, in what seem to us wild, desolate, and, above all, wet and cold places. If you had the whole of the British Islands to base yourself in, why would you choose the places with the worst, coldest, windiest, wettest, weather?

Of course, the climate was quite different in those days – generally warmer for one thing. Plus of course much more ‘life’ happened by sea rather than land – travel, trade, etc, and in many ways Orkney would have been a very convenient place for sea travel across much of the Northern Atlantic. This is certainly how the Vikings later viewed them. In terms of trade routes, Orkney is at a crossroads between Scandinavia, the mainland of Great Britain, and the islands of the North Atlantic to the west and north.

Specifically with regard to the Orkney Islands, there’s evidence of people living there as early as the 3000s BC. When I was a kid, when I could still count my years on my fingers, one of my great aunts gave me for Christmas one year a child-friendly cartoon/picture book all about a historic site called ‘Skara Brae’, and for years it was the only thing I ever really knew about Orkney. It turns out it’s one of the most important and largest tourist sites on the whole of the archipelago, and often sees cruise ship passengers loaded up into coaches for the 16 mile journey across Mainland; the car park at Skara Brae is pretty big and the site is, compared with the rest of the islands, rammed with people.

Except when I went, obviously, because of Covid.

Overview of several of the houses at Skara Brae.

It’s not a huge place, but for what it is, it’s pretty spectacular. It’s on the western edge of Mainland, and is what remains of a neolithic village, and was re-discovered accidentally after a storm washed away some of the of the cliffside, revealing stone foundations. These were later protected from further storms and excavated, revealing 10 sunken ’round houses’ built with flagstones. Although many of the items and trinkets they would have contained had been plundered or washed away over the years, what remains is a pretty well-preserved framework. Remember, this site is further back in history from the Pompeii deluge than we are from Pompeii – these are amongst the oldest houses in Europe, and only a little younger than ancient sites like Ħaġar Qim in Malta and several sites in Turkey in age. Indeed the pathway from the visitor centre to the cite itself is lined with plaques depicting events in history, getting further back as you get closer.

Close-up view of one of the houses at Skara Brae.

Doubtless the site was much larger when it was built. We, well geologists anyway, know the land has shifted somewhat over the millennia, and while always a coastal village, the nearby bay didn’t exist and presumably a considerable part of the village has been unknowingly lost to the sea over time. That said, what remains is still pretty impressive, especially given its age. Note that you can’t walk ‘into’ the houses; rather you go around the edge of them, on top, kind of overlooking them and are able to peer into them.

What we don’t know is when or why it was abandoned, nor do we know a lot about the people who lived here. We do know they were heavily dependent on the sea, with evidence of both a seafood diet and a considerable use of oceanic products like shells and seaweed. We also know they used the interior of the island for agriculture and, just as the people there do these days, farmed cows and sheep.

Close-up view of another of the houses at Skara Brae. You can see how close the sea is.

Wikipedia tells me that Skara Brae is also the site of the earliest known record of Pulex Irritans, the Human Flea, in Europe. I don’t know how I feel about this.

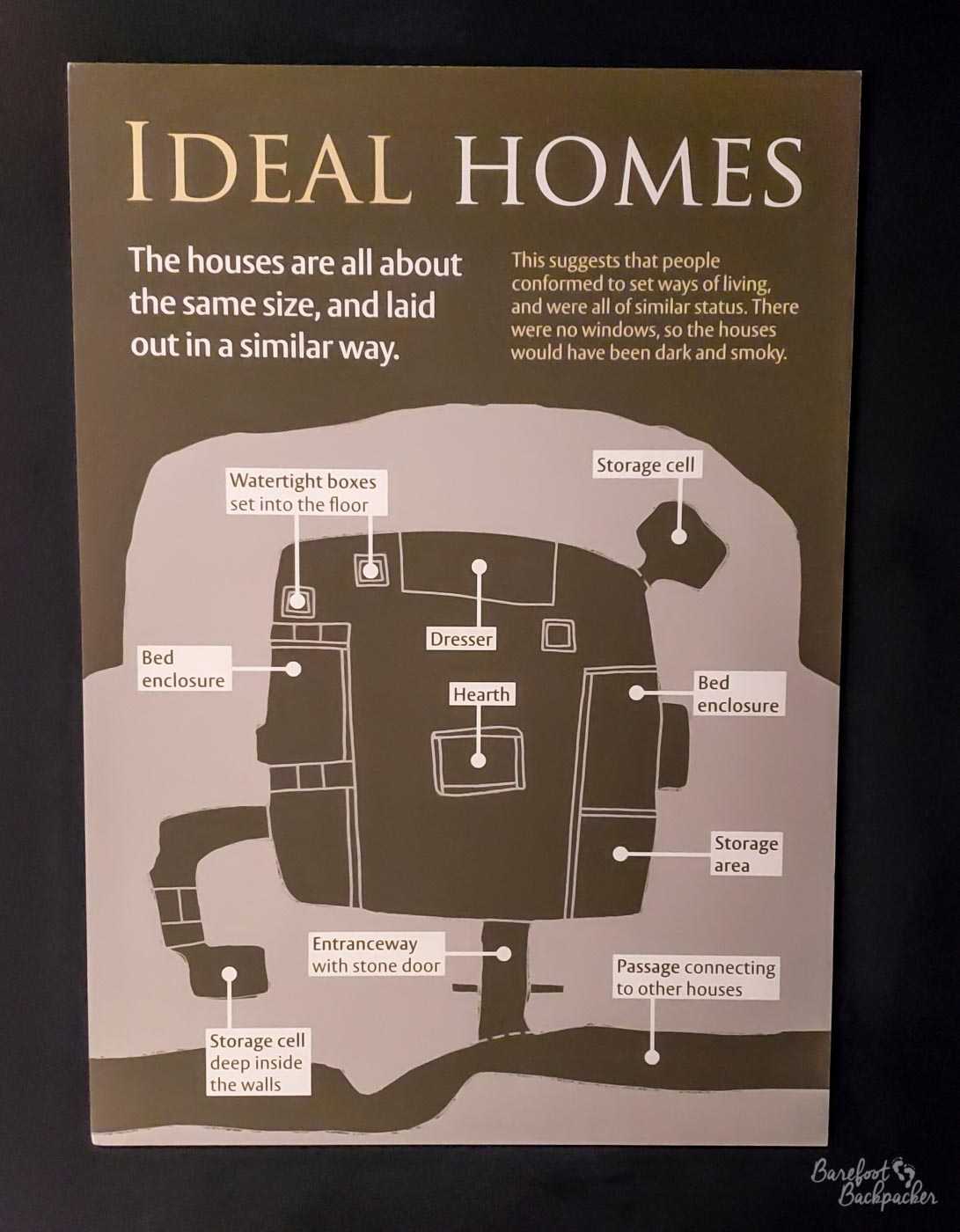

Floorplan of a standard Skara Brae house.

A few miles SE of Skara Brae are a couple of other neolithic sites of importance, although there’s no evidence of any direct connection between any of them. The most important two are both described as ‘henges’, a word most of you probably associate with Stonehenge, down in southern England. And yes, it’s the same form. A ‘henge’ is a particular kind of structural layout – think of it as being a defined circle of mostly flat land, surrounded by a ditch. Although the circle doesn’t have to contain anything of any importance, the most common and notable tend to contain large stones or wooden structures.

Stenness Standing Stones. With sheep.

The smaller of the two is at Stenness, pronounced ‘stane-is’, and is an old Norse name meaning something like ‘headland where there are stones’ – indicating the stones were probably old even to the Vikings. In fact, the site is believed to have dated from around 3100 BC – so contemporaneous with Skara Brae. This makes it the oldest stone circle in the British Isles, and thus amongst the oldest still surviving of its type in the world.

The archaeological evidence suggests at one point there were 12 stones set in a circle, although these days only 4 stones remain. The stones in the main circle stand around 5m tall, though near the road there’s a much taller stone that may have been paired with another to create a kind of gateway.

One very large standing stone, between the Stenness ring (visible in the background) and the bridge over the channel (behind the camera).

It’s located where two lochs meet; there is a very narrow channel between the Loch of Harray to the east and the Loch of Stenness to the west (from where there is access to the sea). These days the main road towards Skara Brae crosses the channel on a bridge, but in the days when the the ring was built and used it’s believed the land was more like marsh or swamp, and the way north was secured by means of a series of stepping stones. In any case, the viable land here is so narrow that the ring would have been hard to avoid – suggesting its importance to the local population, although what its importance was is still unclear.

Another shot of the Stenness Standing Stones, making it clearer they’re a ring.

Behind the stone ring, along a grassy path for a couple of hundred metres, is a reconstruction of a contemporary village. This is known as Barnhouse, and the buildings are similar in style to that at Skara Brae, being slightly sunken into the ground and lined with flagstones. Not much of the buildings survived to the present day, so which exists here is largely a recent re-creation based on the evidence rather than something genuinely old like at Skara Brae, but it still gives a good impression as to the sort of place the people lived. Given its age and its location, it’s likely the people here were those who directly used the circle at Stenness.

One of the reconstructions at Barnhouse – you can see similarities with Skara Brae though.

What is also unknown is whether whatever usage the site had ceased when a larger stone circle was constructed a couple of km north, on the other side of the loch channel. The Ring of Brodgar is believed to have originally contained 60 stones, of which 27 still exist. Unusually, these form pretty much a perfect circle, a fact which probably would cause the producers of the Ancient Aliens TV Series to orgasm in their underpants. It’s just over 100m in diameter, which makes it one of the largest in the whole of the British Isles. It’s on slightly raised ground overlooking the lochs, and in the empty evening air, even on a summer’s evening, still exuded a sense of awe and mystery.

The Ring of Brodgar, as seen from a neighbouring mound. You cab clearly see how ringy it is.

No-one quite knows when the Ring of Brodgar was constructed, although the latest theory is for a date around the end of the 2000s BC. This would make it several hundred years after Skara Brae was believed to have been abandoned, which suggests that while there’s no connection between the two, certainly there was settled life on the islands pretty much constantly over the period, so when people ask ‘what happened to Skara Brae’, the answer might well me the mundane ‘they moved slightly further inland’.

The Ring of Brodgar – here the whole width is visible though taken more on-level so you can’t see the far side.

Both Brodgar and Stenness have been ret-conned by later invaders, historians, and weavers of folktales as being places of mythical and ritual practice, of magical ceremonies and archaeological observatories, as sites of this age and provision often are. In truth, we don’t yet know; we’re still working them out.

All three of these sites, together with a fourth, the cairn and grave at Maeshowe, and a further series of scattered ancient solitary stones, cairns, and brochs in the area, make up the ‘Heart of Neolithic Orkney’ a UNESCO World Heritage Site. On my visit, Maeshowe was closed for Covid because it’s an ‘enclosed’ museum rather than an open-air venue, but when you are able to visit it you’d find a chambered cairn; to all intents and purposes it’s a graveyard. There’s a long (10m or so) stone passageway from outside that leads into a chamber, off which are a number of smaller cells. One interesting facet is that the entrance passageway is located such that the sun shines directly down it either side of the Winter Solstice. Cue all manner of theories about ritualistic beliefs around light v darkness, and whether souls of the dead were transported to the afterlife during the Winter Solstice on the sunbeams.

The Ring of Brodgar – here the ditch is clearly visible so you can tell just how much of a plateau it’s on.

Although the Heart of Neolithic Orkney definition only covers this part of Mainland, there are neolithic sites scattered across the whole of the archipelago. Just off the north-east coast of the western half of Mainland is the island of Rousay, which has around 15 chambered cairns on its own, and, together with the significantly smaller neighbouring islands of Egilsay and Wyre, contain over 160 sites of neolithic interest. Not bad for an island that’s only 5 square miles in area. The majority of sites on there, like Maeshowe on Mainland, are ‘indoors’ (or otherwise covered) and were therefore closed during my visit to Orkney. Still, it gives me an excuse to go back.

Most of the other islands also generally have a couple of cairns, brochs, or stones on them, including Eday, Stronsay, and Shapinsay, and of course Papa Westray has something even more noteworthy, but that’s a story for another post.