As you may know, the Outer Hebrides have been inhabited for several thousand years. My limited research has suggested that the weather up here was a little warmer in those days; certainly it seems like a bleak place to make your home now, but of course times change. Maybe in 3,000 years people will wonder how on Earth we thrived in places like Tunis.

Stone Circles and Meeting Places

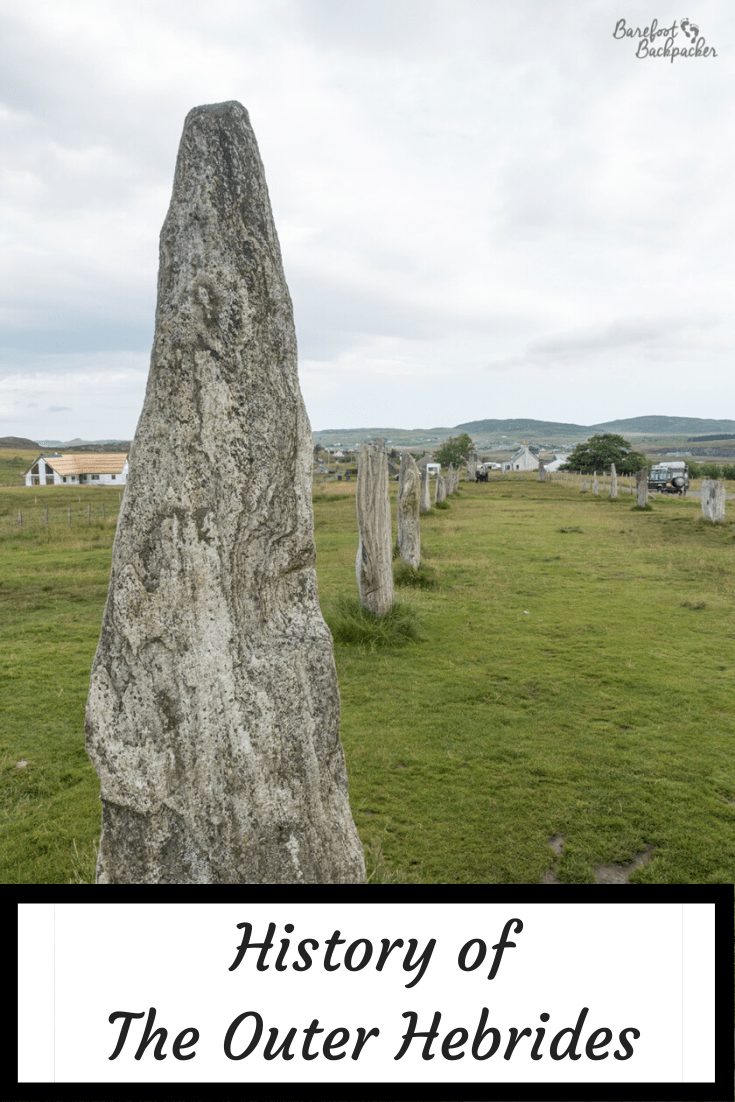

Let’s start at Callanish, on the island of Lewis. This site is famous for its stone circle; it’s been compared with sites like The Ring Of Brodgar and Stonehenge in its provision. While it’s not quite as ‘complete’ as the site further south, it’s certainly quite an impressive place – plus of course here is not only far less crowded but also you can wander right up to the stones & admire them as they were meant to be. It’s also free.

The stone circle at Callanish I, on Lewis

There’s three sites in total, within a couple of km walk, but most people stick around the largest and most complete site known in the literature as Callanish I – there’s also a small museum here that gives you a brief potted history of the site, its rediscovery, and stone circles in general.

Another view of the stone circle at Callanish I, on Lewis

The initial circle was constructed initially around 2700BC, though they were changed over the centuries afterwards (not just added to, but moved around a bit too), before being abandoned around 1000BC. Although the knowledge of them remained locally in the years since, they ended up being naturally swallowed by peat (not a euphemism), and were only re-excavated in Victorian times.

View of the stone circle at Pobull Fhinn, North Uist

A much smaller stone circle, but still one that has an atmospheric and spiritual air, is on North Uist and known as Pobull Fhinn. This translates as ‘Fionn’s People’ or ‘Fionn’s Tent’, and is a reasonably large ancient (between 1000 and 2000BC) stone circle on the east coast of the island. Many of the stones are still in situ, although it’s less easy to notice as the site is fairly overgrown and the stones kind of meld into the heather. That said, in its heyday, it must have been an impressive location.

About 1km, and a couple of thousand years away, is the remains of a chambered cairn called Barpa Langass. This is possibly one of the oldest still-standing buildings in Europe, and is the remains of a chambered cairn. It stands about 35m up the side of a hill called Beinn Langass, on the SE side of the island.

the stone cairn at Barpa Langass

Although a burial site for an apparently important person (extensive grave goods have been found in the area), the cairn itself was used as a communal meeting place for several centuries – it’s a pretty good site for it in the sense that it’d be visible from quite a way away over the fjords and flood-plans. Until recently it was even possible to go inside one of the chambers but the roof of the entranceway gave way a couple of years ago – that it took so long to collapse is testament to ancient builders. Everyone I know who lives in a house built in the last 30 years really hates them.

Housing

Speaking of houses … obviously where there are ruins of ancient communal meeting places, there is going to be evidence of the local population.

In the dunes on the western side of South Uist, just behind a graveyard, is a site known as Cladh Hallan. This is the site of some Bronze Age stone roundhouses, occupied from around 2000-1300BC. There’s (obviously) not a lot left of them but its clear from the remains and the indentations made in the ground how big and what shape they were.

Foundations of one of the round houses at Cladh Hallan.

These roundhouses were also home to the only mummies found in the UK; although not well preserved, bodies (of people who’d died about 300 years apart) were found that had been purposely buried in peat bogs to preserve them, before being reburied around 1100BC, for unknown reasons.

Moving on to Lewis and more recent in time, a little north of Callanish is Dun Carloway. This is an example of a broch, or iron-age drystone building, common in the isles. Dating from around 100BC, initially it seems to have been used as a house with several floors – livestock below, out of the way but also providing heat upwards, then a living area, then a sleeping area. Over time its use changed & it may have been used as a fortification or a lookout post – it lies on the hills overlooking a bay & the western sea. All that remains now is the basic walls/framework, tho it’s still one of the most complete examples of a broch to be found.

Remains of Dun Carloway broch, on Lewis

Further north still, & two millennia afterwards, is a museum dedicated to the ‘blackhouses’ that were a common form of housing over the last couple of hundred years. They’re generally long buildings with thatched roofs (& no chimneys – the smoke from the hearth dissipated through the roof. You can imagine how that made them feel inside.), divided into 2 or 3 rooms, &, while some people nostalgicise about them, they were quite pokey and unhealthy places to live. People were rehoused from the blackhouses here as recently as the 1970s, and the buildings preserved as a testament to recent culture. I found them strangely Asterixian.

Example of one of the Blackhouses at the museum on Lewis

One of them is now a small hostel so you can stay in one to get the full authentic experience. Obviously I didn’t.

Bonnie Prince Charlie

A man with many names, both as nicknames (eg ‘The Young Pretender’), and as given names (‘Charles Edward Louis John Casimir Sylvester Severino Maria Stuart’ – one supposes if his parents were angry with him in his youth they’d have got as far as ‘Sylvester’ and gone, “you know what, it’s fine”), many of the islands in the Outer Hebrides claim an association with Charles Stuart, the claimant to the British throne in the middle of the 18th Century.

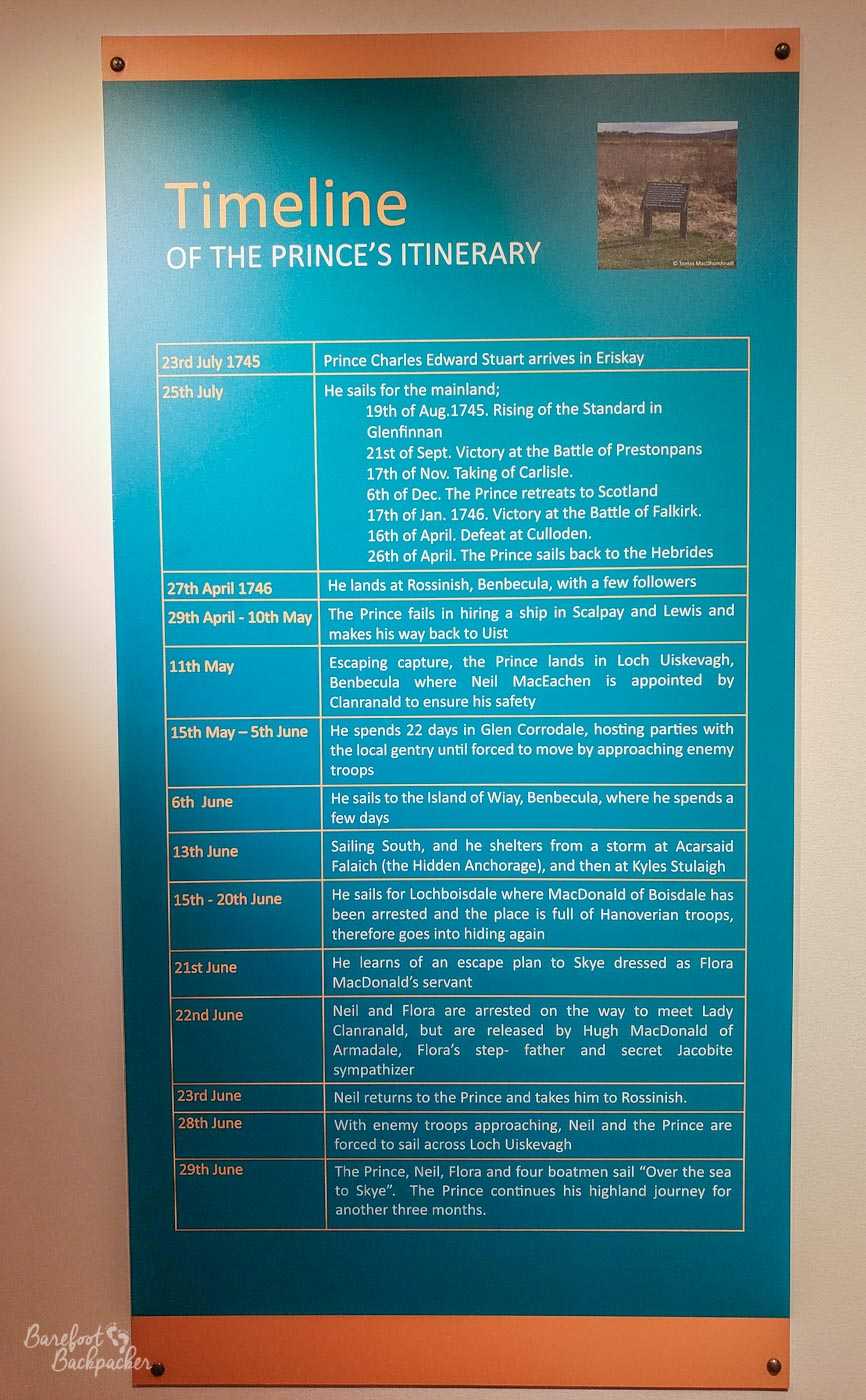

Timeline of Bonnie Prince Charlie’s adventures in the Outer Hebrides

His grandfather had been King James II (of England) & VI (of Scotland) before being overthrown in an invasion by the Dutch in 1688, because he was both overly Catholic and tending towards a return to Charles I type rule, and we’d just fought a civil war about that sort of thing; his father had tried and failed to reclaim the throne in 1715, so it was left up to him to come out of exile in France and make one last attempt on his father’s behalf.

While Eriskay was his first port of call in Scotland, from where he started his invasion of the Kingdom of Great Britain (and there’s an out-of-place flower that grows there, that’s said to have fallen out of his pocket on landing), he’s most noted in these parts for coming back here after it all went tits-up. He’d reached just past Derby, 120 miles from London where the government was genuinely a bit fearful, but lost momentum and faith in, well, the French to join him, and headed back North, being decisively beaten at the Battle of Culloden so badly, the resulting retribution pretty much destroyed the Highlands for centuries.

Cairn dedicated to Flora MacDonald around the site of her house on South Uist

After escaping to Benbecula, he pottered around the islands for a while until he realised he had to get back to France. He was aided in this by South Uist resident Flora MacDonald, who disguised him as her maid ensured he got safe passage to the Isle of Skye, from where he was picked up by French boats. Flora was an interesting woman in her own right; she seems to have been quite well educated, and her step-father commanded the local militia, which though pro-government, gave her the gravitas to provide help. A couple of years later she was arrested for her role in his escape, but got on so well with the King’s son that he left her off. She ended up marrying a solider son of a landowner, emigrating to America until she was kicked out after the War of Independence; they eventually retired back to Skye.

Possible remains of Flora MacDonald’s house on South Uist

Milton, on North Uist, is the township she was born and brought up in, and there’s several remains of 18th Century houses that are scattered in the fields of sheep; while its specifically stated that the ruins identified may not be the exact ones that Flora lived in, they provide a good representation of the style and location.

Whisky Galore

I’ll take “Films I’ve never seen” for £200!

The island of Eriskay’s most famous claim to fame is that in 1941, a cargo shop called the SS Politician, sailing between Liverpool and Jamaica, ran aground on the island in bad weather.

This itself would be marginally notable, but for its cargo. As well as generic goods including motor and plumbing parts, and a suspiciously large amount of banknotes (several million pounds in today’s money), the ship was carrying over 300,000 bottles of whisky. Given this was Scotland, during wartime rationing, you can probably guess what happened next.

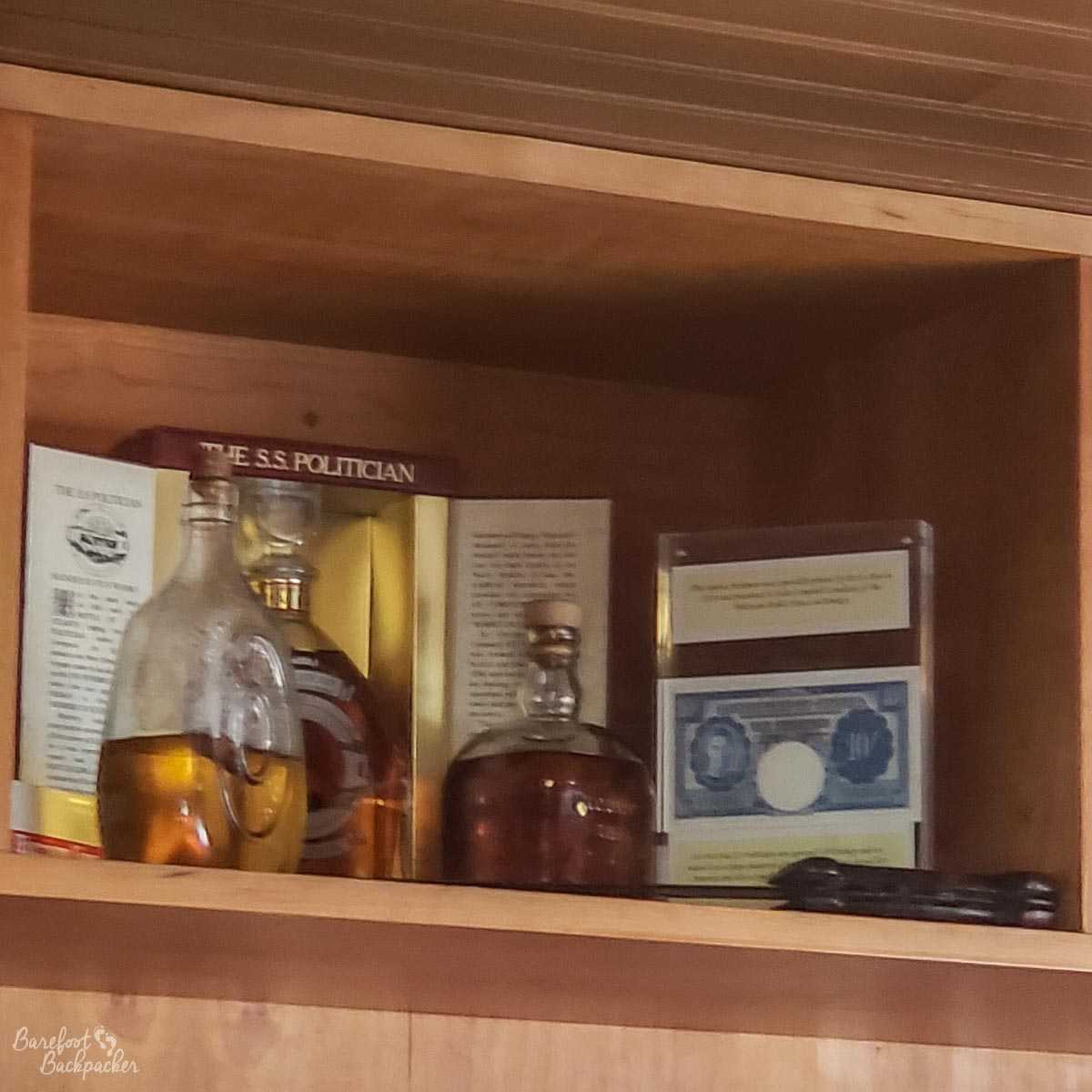

Pictures and details of the SS Politician, seen in the pub

The local customs officer was not amused with the locals’ ‘unofficial salvage operations’ and, with the reluctant local police in tow, went on a crusade to both recover the whisky and charge those involved with theft (his view was, as they hadn’t been legally purchased, no duty had been paid on these bottles and they were still the property of the ship owners). To prevent further issues, and official salvage attempts failing, he ended up having the whole ship blown up with dynamite.

The event was used, soon after the war ended, as the basis for a novel called ‘Whisky Galore’ by Compton Mackenzie, an English writer and actor who’d made a home on nearby Barra in the 1930s, and a couple of years later the novel was filmed as an Ealing Comedy. Mackenzie himself was originally from Hartlepool in the NE of England, but he later became an ardent political acitivist in Scotland and one of the founders of the SNP. He’s buried on Barra in the church near the airport.

Genuine bottles of ‘Whisky Galore’ whisky, behind the bar of the SS Politician, on Eriskay

Bottles of the whisky still turn up from time to time – indeed the pub on the island is named after the ship in question, and has much memorabilia relating to it, including a couple of authentic bottles behind the bar. Due to the corks rotting and seawater getting into the bottles, the whisky is now undrinkable, but it’s still a talking point.

I didn’t get to ask too many questions as on my visit there was a wedding going in the pub grounds so everything was a little bit busy and off-kilter.

Disaster Memorials on Vatersay

The southern island of Vatersay, despite not being very big (3.7 sq miles, or about 1½ times the size of Gibraltar), was the scene of two notable transport crashes. On the ridge that separates the two beaches in the centre of the island is a monument to a boat disaster in September 1853. A ship of emigrants (the Annie Jane) from the UK to Quebec hit rocks just off the western beach and sank quickly; 350 people died, about three-quarters of those onboard; it sank so quickly that the few locals who could help couldn’t help much.

The memorial to the Annie Jane shipwreck, just off Vatersay

Next to the road on the way along the eastern coast is a monument to another disaster – an American plane crashed here in May 1944. The Catalina, an American flying boat, was on a navigational exercise and crashed into the slopes of the hill after apparently believing a lighthouse they could see was south of Tiree, rather than its actual location just south of Vatersay. Nine of the scheduled crew of ten perished. Parts of the remains of the plane still lie on the slopes near the monument; people occasionally decorate them with flowers.

The memorial to the crash of the Catalina flying boat; remains still in situ

Miscellaneous Historical Titbits

- Castlebay, the main town on Barra, is named after a castle. In the bay. You can see what they did there. This is Kisimul Castle, apparently not worth the trip to see especially, but notable enough – believed to be around 500 years old.

- Carinish, North Uist was the site of allegedly the last battle fought in the British islands with bows & arrows (1601 – MacDonalds beat MacLeods). Parts of the battlefield have distinctive names, like the ‘ditch of blood’.

- Ruins of old churches are scattered around the islands, though Carinish has one of the largest – the “Church of the Holy Trinity”, which may even have been a monastery or college. Although now in ruins, it’s relatively simple to visualise how atmospheric it must have been to be spiritual here.

- The island of Vatersay was, in more recent times, famous for the Vatersay Raiders – one of several groups of locals across Scotland who occupied land they felt had been unfairly taken from their ascendants by absentee landlords. These land raids eventually led to a change in the land ownership laws, so sometimes protest does work.

- And then of course there’s the whole history of St Kilda.

—

Like this post? Pin it?