“Our flight time will be about 2½ hours, thanks to a strong tailwind. The current weather in Sofia is sunny, with a temperature of -12°C. We hope you enjoy your flight.”

Hang on. Did he just say minus twelve degrees Celsius? MINUS TWELVE?! I mean I know I’m wearing a thick fleece, and have gloves & a hat in my bag, but seriously … ?!

To be fair, I needn’t have worried. By the time I landed in Sofia it had risen to a balmy -5°C, and for the whole time I was there it was clear skies and no wind so it never really felt as cold as the temperature suggested. The snow on the ground was still mostly solid and not slushy or too icy, and I never made use of the hat or gloves in the end. Yes, I was wearing shoes …

The best shot I could get of the mountains outside Sofia. This may or may not be Vitosha, but you can get the general idea.

Bulgaria might sound like an odd choice for a weekend break, especially in the middle of Winter, even more so given that I’m not a fan of winter sports (Vitosha mountain, which starts from within Sofia’s suburbs, rises to just under 2,300m and is a popular ski resort), but there’s more to it than snow, Soviet concrete, and the Cyrillic alphabet.

Religion is one of the prime movers in Bulgaria – while not as strongly religious as, say, Romania or Malta, it’s definitely a much stronger part of the national psyche than in the likes of the UK. The main religion is Bulgarian Orthodox – one of the older branches of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, and one adhered to by around 60% of the population. There’s a series of small churches scattered around the city from throughout history, but the largest of them is the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral on the East side of the city.

The visage of the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, shimmering in the snowlight. Or something.

It’s a hugely impressive building on the outside, and dominates the surrounds. It’s a fairly recent construction ….. and, though it doesn’t feel like it, it’s built on a hill so would have been visible from quite a distance [presumably for maximum effect they should have put it on the top of Vitosha but I imagine that would have been somewhat impractical. Obviously if Bulgaria was Catholic there’d be a Cristo Redentor on there like Malta or Timor-Leste, but … they’re not]. The name comes from the liberation of Bulgaria at the end of the 19th Century by the Russians – originally they wanted to call it after the Russian Tsar but the religious authorities said cathedrals could only be dedicated to saints, so it was named after the Tsar’s favourite saint. It does get renamed occasionally when Bulgaria and Russia fall out.

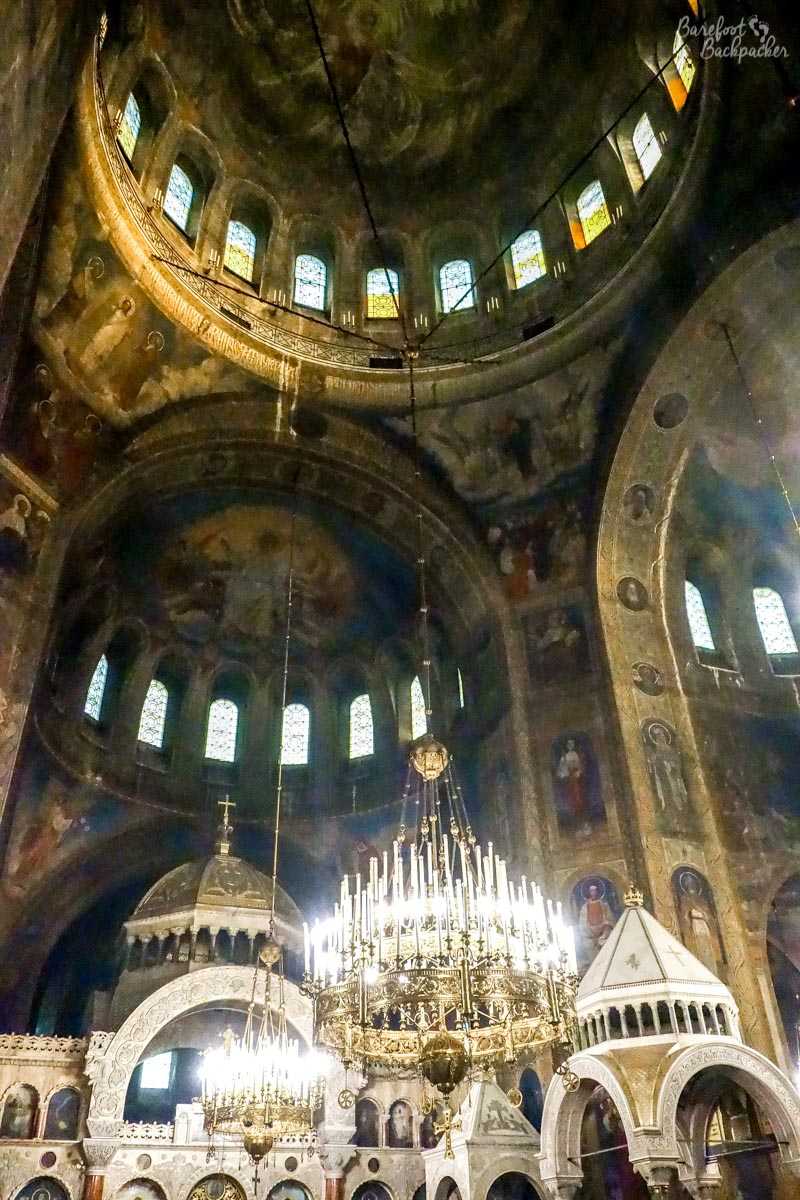

Shot from the inside of Alexander Nevsky Cathedral. It’s a tall place but I found it less interesting than I imagined. And yes, I did pay for a photo permit (10 lev).

I have to admit to being less than impressed by the inside – it was more a kind of faded opulence; overly dark, not as rich and over-the-top as Catholic cathedrals, not as internally architecturally visually impressive as Anglican ones. But maybe that’s just me. The walls were lined with the usual Christian Iconography, but apart from pretty wall paintings and the altar area, it was all a bit drab for me.

Another Orthodox church worth a look is Sveta Nedelya, near Serdica metro station. This is quite a new building (dating from the early 1930s) but there’s been a church on this site for over 1000 years. It’s quite an impressive edifice and, whisper it softly because it’s a church, I found the internal decoration to be a little more spectacular than that of Alexander Nevsky.

The outside of the Sveta Nedelya church. It being surrounded by trees makes it quite a nice location.

The reason it’s ‘new’ is because it was the scene of Bulgaria’s biggest terrorist attack; in 1925 the Bulgarian Communist Party launched an assault on the church in an attempt to assassinate the King (Boris III). It was a meticulously planned operation; they aimed to wipe out most of the government of Bulgaria by firstly assassinating a high-ranking figure (they settled on leading army general Konstantin Gregoriev), and then killing the rest as they attended his funeral. 150 people died, over 500 were injured, but Boris III himself survived, by virtue of … arriving late and thus not being on site at the time the bomb went off. Ultimately then the plot failed, and the leading conspirators were executed.

The inside of the Sveta Nedelya church. Typically opulent Orthodox church; on my visit filled with people lighting candles.

Bulgarian Orthodox of course hasn’t always been the dominant religion; around 8% of the population are Muslim (predominantly a leftover from the Ottoman era), while there are still small numbers of other Christian denominations, as well as Jews. There was a substantial Jewish population in Sofia before WW2, but very few remained after the war. Not for the reason you think either; despite siding with the Nazis, Bulgaria is quite proud of having had no Jews killed in the Holocaust – rather, upon the communist takeover post-war, travel to the outside world was heavily restricted, except for preferential treatment for Jews going to Israel, so most of them emigrated.

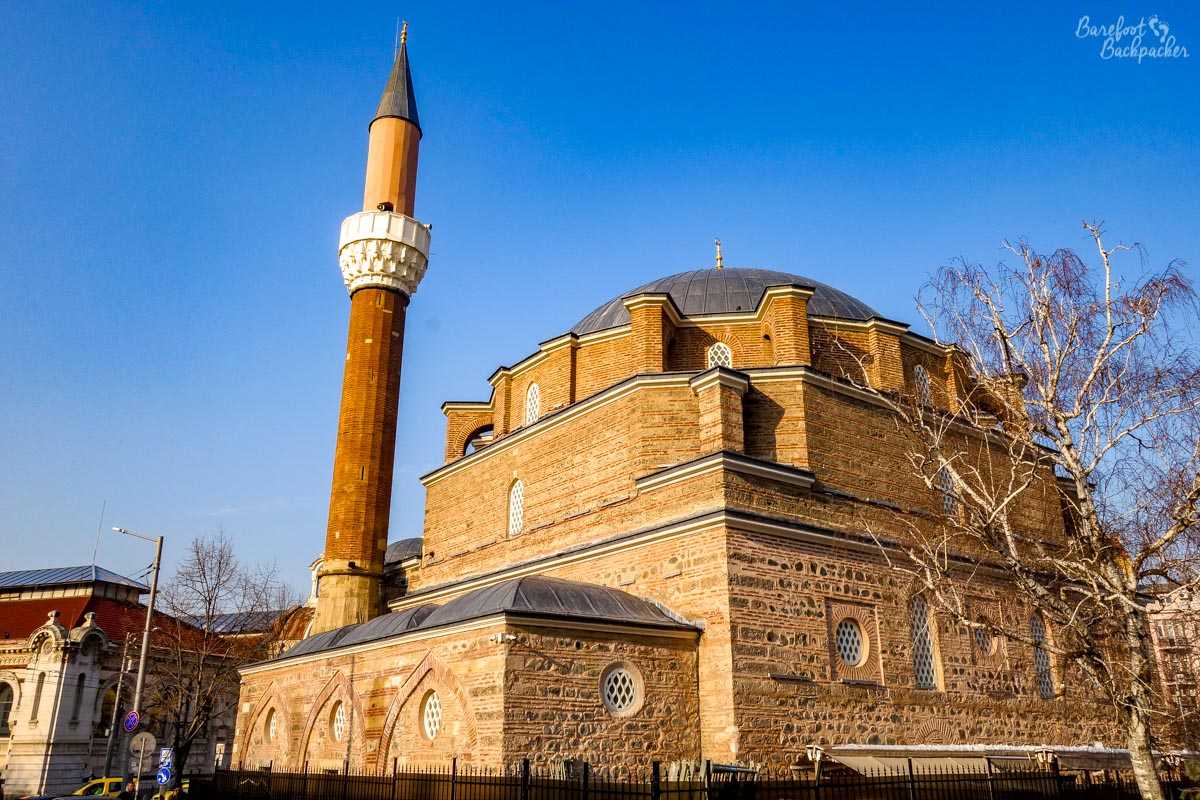

Banya Bashi mosque; built in the 16th Century and pretty much the only mosque left in Sofia city.

This religious history has led to the famous ‘square of tolerance’ in the centre of Sofia, at Serdica Metro station. While not all directly on the square, if you stand on the main road above the Roman ruins, you can see a small Bulgarian Orthodox church, a large mosque (the only one left in the city), a huge synagogue, and, just off the square, a small Catholic church. It’s believed to be the place in the world where four different religions are the closest to each other.

The small and quaint Sveta Petka church, in the centre of Sofia.

The small Orthodox church (Sveta Petka) has an interesting history in itself. It seems to have been built during the Ottoman period and consequently looks unassuming, a bit like a house. One of the aspects of Ottoman rule was that, although the official state religion was Islam, other religions were tolerated and free to worship. There were some restrictions (including that non-Muslim-owned buildings couldn’t overlook Muslim ones), and churches (and synagogues) had to be hidden away and not ‘obvious’ to the local population. As such, this was designed to look like a house, and had few windows.

As stated, the church is near the Roman ruins. Sofia has been inhabited since ancient times, but the Romans were the first to establish it as an important town, which they called Serdica, possibly after the ancient tribe that lived in the area. Some ruins of ancient Serdica remain, mainly a small area in central Sofia where a road and some small buildings have been excavated. Much of the rest of Roman history has been built on – such is the problem with continually-occupied cities.

Part of the excavated ruins of Serdica. It’s interesting to see the history here; Roman ruins, mediaeval churches, and the building on the left was constructed by the Communists in the late 20th Century.

One of the reasons the Romans came here was because of the natural mineral water; it was (and still is, in part) a spa town – although many of the baths have closed or been repurposed, the springs themselves (just to the East of Serdica) are still used daily by locals to fill up their water bottles and kegs.

People filling bottles of water from the hot spa springs in the centre of Sofia. Nearby is an old bathhouse, now a history museum.

Even in the Roman era though, religion figured strongly in the city. Indeed in 311, the ‘Edict of Toleration’ was issued from Serdica by the Roman Emperor Galerius, being the first legal recognition of Christianity in the Roman Empire. A couple of decades later (in 343), the “Council of Serdica” (a synod, or church council) took place here; this saw one of the first splits (schisms) to occur between the ‘Western’ and ‘Eastern’ Christian churches – although both sides came to an agreement later that century, the clash between Rome and Constantinople to have the dominant path of Christianity continued for many years until the final split in the 11th Century.

It might appear that all I really saw were Roman ruins and churches. This is generally true. Also in the area that I didn’t get to see, and I’d recommend if you have a bit more time, would be Vitosha mountain itself, the huge Rila Monastery (which requires a day trip from Sofia), and, despite my inherent dislike of museums, the Museum of Socialist Art in the South of the city.

The grounds of the Socialist Art Museum, showing some of the statues in situ.

That museum of Socialist Art is in the South of the city, close to G.M.Dimitrov metro station and in what at first glance seems to be an area filled with commercial buildings and the huge Traffic Police complex. It’s closed on Mondays, but I managed to get a couple of shots of some of the statues in the grounds; basically it’s the last resting place of all the old Communist memorabilia that were removed in the early 90s.

So, in general, I’d say Sofia would be definitely worth staying for a full weekend – there’s enough here for at least two days, three or four by using it as a base for day trips; it’s quite easy to get to much of the rest of Bulgaria by either train or regular bus, and indeed places like Niš in Serbia are only 3 hours away. Just make sure you dress for the weather …

—–

Like this post? Pin it!!

—–

Dates Visited: 27-29 January 2018.

Other nearby cities include Belgrade (Serbia), and Plovdiv (Bulgaria).

Well written! I have to come back again since I obviously didn’t see all there is in way of interesting buildings.

Thank you 🙂 Yes, I was only there for a short time, so I’m sure there were things I missed too!