As I’m sure you all know, in the summer of 2019 I hiked across Great Britain, along with my friend Becky The Traveller. The plan was to go from the furthest Easterly point to the furthest Westerly point of the mainland, which we achieved in 57 days, covering 952 miles/1532 km. I blogged about the final few days in Ardnamurchan, but here I want to talk about the start of the route. The first week we were hiking on the Norfolk Coast Path, a marked long-distance footpath that runs along the coast from just south of Great Yarmouth, at the Norfolk/Suffolk border, to Hunstanton, a distance of just over 130km/80 miles.

Norfolk is a county noted a lot for its countryside. Although our hike went along the coast, incorporating beaches, wildlife reserves, sand dunes, and clifftops, inland Norfolk is of course most well known for the Norfolk Broads – a series of wetlands and rivers that people hire boats to sail along. I visited these back in 2008 my friend and nemesis Sarah joined me on a five-day exploration of the broads, the net result of which is that she vowed never to go on a boat with me again. Apparently she didn’t trust my piloting. To be honest, who would.

But, for completeness’ sake, let’s start over the border, in Suffolk.

Day one: Lowestoft to Caister

Ness Point is the furthest easterly point of Great Britain, and (wind farms and abandoned sea forts aside) the UK itself. Now, you might imagine that this would have the same draw as Land’s End or John O’Groats, which, despite neither being points of any significance, have a large cache of kudos attached to them, and activities and tourist attractions to boot. And you’d be completely wrong.

Ness Point, the starting point of our Hike Across Great Britain, and effectively the Norfolk Coast Path. Feet and picture provided by Becky The Traveller.

It’s easy to spot – there’s a huge compass monument on the floor with directions to hundreds of places across the UK and Europe, including Ardnamurchan Point which is 451 miles in a direct straight line. The surroundings however … it’s on a concrete promenade next to the rocky shoreline, about a mile and a half out of Lowestoft town centre, at the seaward side of an industrial estate and directly behind a Birds Eye Frozen Foods factory. We felt that if we were ending the walk here, it may have had the feel of a bit of an anticlimax – that being said at least it would be an easy place to recover in and then get out of.

Once away from the grey concrete that defines Lowestoft, the proto-path settles down into the same pattern that’s repeated all along the cost – sections on the beach, sections in the dunes, sections on the cliff-top on mostly grassy trails. The Norfolk border itself isn’t signposted; only a reading of the map suggests that the Norfolk Coast Path starts where a long alleyway from a nearby road joins, close to one of the many caravan parks we pass en route.

The walk into Great Yarmouth is one of the longer beach sections, sandy and a little shelly underfoot, which runs alongside one of the many concrete walls that protect the shoreline from the advancing waves. The sea is particularly troublesome in these parts, as we saw over the next couple of days. This was also the section we saw a large dead seal, which Becky noted smelt worse than we did.

The path through Great Yarmouth itself, from Gorleston, is very suburban, being one of the only sections of the path to run on public roads. The reason is because the town stands just above the mouth of River Yare, which enters the sea at quite a narrow angle. There is no way over the river from the mouth to the town itself, so for just over 4km you’re stuck on pavements. That part of town isn’t the prettiest, passing as it does some riverside industrial estates. After finally crossing a bridge in the centre of town though, the signs bear due east and only 1km further on you’re at the beach again.

Great Yarmouth Promenade – fairly typical of the British Seaside Resort style.

Great Yarmouth is the largest settlement on the Norfolk Coast Path (at 38,500 people it’s the third largest town in Norfolk, and if you include the 24k in neighbouring Gorleston it’s considerably larger than King’s Lynn), though Lowestoft is a bit bigger still. Nevertheless we didn’t spend long in the town – only enough to fill up our water bottles and, you know I don’t even think we grabbed a snack. In part this was because we wanted to wild camp somewhere in the dunes away from the town, and part because we were hiking, rather than being tourists. It’s a seaside resort, one of the many on the Norfolk coast, and contains the correct combination of beaches, promenades, cafes, pubs, amusement arcades, and other dubious forms of entertainment.

It would be a great place to overnight, but of course we were hikers on a budget so we pushed on, along the promenade and then the coastal path that took a course through the slowly-rising sand dunes until a point just beyond Caister where we found a flat enough and secluded enough spot in the dunes to camp up. Only my second ever wild camp, but despite having a tent that even Becky was confused about, still went better than my first.

Days two and three: Caister to Overstrand via Happisburgh

I’m combining these days as they were both quite short, due to Becky having problems with her footwear causing blisters. I … to be fair it was halfway through day two that I had to abandon any pretence for doing the whole thing barefoot due to one of the paths behind the dunes being pure gravel for over a mile.

Much of these two days was dominated by walking along either the shoreline, or on cliff tops overlooking the shoreline. But I’m mentioning this not as a means to paint a picture of the route, but more to highlight a very important aspect present across this entire path.

We stopped for brunch on the second day at a small cafe near the village of Winterton. Called the Dunes Cafe, it served up a great selection of breakfast sandwiches and small meals, and a good array of drinks. It was a beautiful, clear, sunny day, and the cafe and road up to it, and a little way beyond to the beach, were both proving pretty popular.

I don’t seem to have any pics of the Dunes Cafe itself or its surroundings, but this is the mug of hot chocolate I had there.

Within a year and a half of visiting, the cafe had been demolished, because half of it was teetering on a cliff edge.

The whole of this coast suffers greatly from cliff erosion. Some villages have been moved back a couple of hundred meters over the years, others have been lost. Walking along the beach, you get a sense of it as you can see how tall the cliffs are, but also the patches of them where the sea has worn them away. But it’s only when you’re walking on top of them that you get a fully clear picture as to the extent of the issue. There are places where the route of the path has clearly been lost down what looks like a crater, jutting into the land, and only the repeated patter of hundreds of feet creating a makeshift path along the new edge of a farmer’s field identify the new route. Looking out to where the land once stood, you can see the chasms created, the landslides that have happened. There are no fences to protect you from a false step either – there’s no point really as they’d be pulled down by the cliffs just as soon as they’d be erected. Even the footfalls tracing the new routes have moved over time as the erosion gets closer and closer to the new path.

The part of the coast between Caister and Cromer has been the most affected by this erosion; it’s been estimated that up to 100m of land was lost in 12 years at the turn of this century. It must be said the cliffs here have always been eroding, due to their makeup (soft boulder clay, easily washed away), but the rising sea levels and more frequent storms hitting the coast have been exacerbating it in more recent times. The effects of climate change happening before people’s eyes.

Example of the cliff erosion, near Overstrand. You can see how the path has been re-trodden to avoid the big hole.

Several attempts have been made to mitigate this. Along part of the shoreline, stretching out to sea, wooden or metallic structures have been constructed. These are called ‘groynes’, and they serve to break up the waves, and prevent sediment (beach sand, mainly) from being washed away – the more sand there is, the less the water can reach the cliff to erode it. While not foolproof – some groynes in the area were themselves washed away in big storms this century – it serves as a ‘stopgap’ to allow a couple of decades’ grace while more permanent solutions are found.

One such solution was enacted a couple of months after we walked through, at the village of Bacton. This is a place that was very familiar to me in my previous life in the energy industry; it’s the site of huge storage facilities for natural gas collected in the North Sea oil fields, as well as being the British side of the continental ‘Interconnector’, allowing natural gas to flow between the UK and Europe, and thus allowing easy access to energy from abroad. Obviously therefore being at a location potentially in danger of erosion, alternative preventative measures needed to be undertaken. Using a technique honed in Netherlands (a country well versed in flood and erosion preventive measures), sand has been relocated directly and new entire sand dunes have been created, changing the layout of the coastline and preventing easy erosion. One possible downside is some believe it merely shifts the problem elsewhere along the coast, but for now, Bacton is safe.

The Barefoot Backpacker on Bacton Beach. This is the defined path!

Partly because of erosion, but also because no-one really wants barefoot hikers traipsing sand through a site of national importance, quite often on this section the Norfolk Coast Path is unmarked and scheduled to run along the beach itself. This does lead to issues at high tide since at some points the passage between the sea and the cliff edge is quite minimal, so be careful. The beach here though is quite pleasant, mostly sand with the occasional sea shell and large chunk of palm oil to avoid. This latter substance is brought in by the tide, having been dumped overboard by ships in the North Sea and coalescing on its journey ashore. This is legal if and only if they are at least 12 miles offshore, but either this isn’t far enough or some ships were doing it illegally. One of the major problems from a local point of view is it’s poisonous to dogs. And we met a lot of dogs on our hike in this section.

A lump of palm oil on my lap.

We overnighted on day two at the differently-pronounced village of Happisburgh (they call it ‘Hazebrough’, which I’d never have guessed). Because Becky’s shoes were hurting, we stopped mid-afternoon and went to the pub. Happisburgh is noted for it’s distinctive lighthouse, which looks a little like a candy sweet. It seems this is intentional – it’s so when you’re at sea, you know which lighthouse you’re looking at. It’s also notable for being not only the oldest lighthouse in East Anglia (1790) but the only still operational independent lighthouse in Great Britain. It’s independence was as a result of local action; it was to be decommissioned but the local residents managed to take ownership of it, which meant they also legally had to operate it. It stands slightly onshore, at the side edge of the village, but as the cliffs are crumbling quite quickly round here, who knows how long it’ll stay up for. It’s 26m tall, and stands on cliffs 14m or so high.

The distinctive Happisburgh Lighthouse.

Day four: Overstrand to Blakeney

This day takes you along the beach and promenade of two seaside towns; Cromer (complete with old pier) and Sheringham, and also up one of the very few hills en route – most of the inclines on the path are getting between the beach and the cliff edges, or wandering over the sand dunes. In fact, the this part of the path passes close to the highest point in Norfolk – Beacon Hill (103m), the site of an old Roman camp, is less than a mile off-route between the two towns.

The hill the path goes up though is called Beeston Hill, or, locally, Beeston Bump. After so much hiking on relatively flat land, and especially with 20kg backpacks, it’s a bit of a culture shock even if it’s only 63m and quite a short incline. It’s one of the most popular spots on route and were in the company of many other hikers and daytrippers here, including a local rambling group.

Baby Ian and Dave sitting atop a trig point on Beeston Bump. The town of Sheringham is visible in the background.

Given its prominence, and location right on the East coast of England, Beeston Bump was used as a WW2 wireless intercepting station. It was one of the many sites along the coast where radio signals from The Enemy were picked up. This information was either calculation of the location of the radio transmitter, or the message itself. These details would then be despatched to places like Bletchley Park for further analysis and decoding.

Beeston Hill lies between the two towns, but is much closer to Sheringham, The path sticks very close to the coast here, with only a brief foray inland through the village of East Runton, and a conveniently-sited public toilet. On the way into both Cromer and Sheringham though, the path runs along the seafront and passes an array of beach huts. These pretty pastel buildings are pretty common along the coast, and have a particular ambiance. They stand almost on the beach itself, and are usually used for getting changed into/out of beachwear, storing personal valuables, and, let’s be honest as this is Britain, staying dry and warm out of the wind and rain. You can rent them or buy them outright – and they’re surprisingly expensive for what they are: you often need to spend £10-£20k – think of them as being like a new car. Here, very much, it’s all about location location location! They’re usually really brightly coloured, because presumably it just fits in with the general ambiance. I think it makes an otherwise dull wooden cabin quite appealing.

Example of beach huts – these are at Cromer.

Beyond Sheringham the path goes past a golf course, because of course it does, this is Britain and we have a lot of seaside golf courses. We passed by one of the ground staff who was very proud to tell us this was the 109th best golf course in England or something. I don’t know if that’s an achievement or not. Beyond the golf course is the North Norfolk railway, one of several preserved heritage railway lines in Norfolk, which runs from Sheringham to the small inland town of Holt. It operates steam engines and we were fortunate to see one as we passed.

The next 5km or so are a comfortable wander along the cliff, on a grassy / compacted soil trail of the type common in England. Very barefoot-friendly. This is until you hit the car park at Weybourne beach. Just beyond here, the path diverts onto the beach, to avoid the expanse of the Salthouse Marshes. Unfortunately this is not a sandy beach. It is a 6½km trek along unforgiving pebbles, where the land barely changes much. It’s slightly sloping inland, and almost completely featureless. The only danger is to remember to turn left to pick up the path to Cley – although clearly marked, the shale is pretty wide so if you’re walking at the sea edge, you might not see the signpost or the car park. It’s possible to keep going to Blakeney Point some 5-6km further on, but there’s no way across the marshes from there and the only route is back the way you came.

Cley Windmill. I think you can overnight there. We didn’t.

Cley-Next-The-Sea is a cute little village that is no longer quite next to the sea; these days it’s next to the Cley Marshes, which, along with Salthouse and many marshes to the west, are home to a vast variety of birds and wildlife. Its most famous site is its windmill – a grade-II listed structure from the early 1800s that was once the home of exciting singer James Blunt, and is now a B&B. But one much beyond our budget. We followed the path along the very edge of the marshes to set up wild camp closer to the village of Blakeney, in purely flat land perfect to see the sunset and sunrise.

Day five: Blakeney to Burnham

The first half of the day took us on the around 14km from Blakeney to Wells-Next-The-Sea. For pretty much the entire length of this section, the path (in parts somewhat stony; wear sandals) runs alongside the salt marshes. Inland are fields and the occasional village, while the view to the right is a vast, flat, expanse of shrubland and damp patches. It’s a great place for bird-watching, although this was the location of the infamous ‘is that a golden plover’; ‘all I can tell you is it’s a bird’ conversation I had with Becky. We had really good weather for this bit – one imagines though with no shelter at all, doing this in the rain and wind would be quite soul-destroying.

Example of the salt marshes we walked past. This pic was taken near Burnham Overy Staithe, but they’re representative of elsewhere. No birds.

Blakeney is another small village that used to see the sea as important – it has a small harbour but these days it’s pretty much silted up with mud. It’s possible to still sail along the channels to the sea but you could only do it in a small vessel, like a canoe; what remains of the harbour is filled with small boats which clearly haven’t been anywhere for quite a while. A bigger, and more accessible, harbour is present at Morston, the next village to the west. There’s a large array of vessels here, but these days the furthest they go tends to be sightseeing and birdwatching at Blakeney Point. Geographically, this also marks the point at which the coast stops going any significant distance north, and heads due west.

The harbour at the village of Morston, just west of Blakeney.

The only major settlement on this part of the route is Wells-Next-The-Sea. This is another seaside town, in the mould of Sheringham. It also has a harbour, a much more liquid one, from where they apparently do a lot of crabbing. It’s also a great place to have lunch on a really hot day overlooking the harbour, as there’s enough cute ice-cream shops and a couple of small supermarkets to get you through. Just don’t leave your hiking poles in the supermarket and have to run back in the heat from your lunch spot at the harbour to get them, as my hiking partner did.

Alongside the harbour runs a long path northwards to meet the coast – this is really popular to walk/jog/cycle along. After just under 2km it reaches the coast, and the large expanse of the Holkham National Nature Reserve. – an area of pinewoods, sand dunes, and a large beach, all of which cover an area of about 4km², or 6 times bigger than Gibraltar. It’s England’s largest designated ‘National Nature Reserve’, and itself part of the whole North Norfolk Coast SSSI, so it’s well protected. Again,the biggest draw of this part of the coast is the birdwatching.

The path through the pinewood section of the Holkham Nature Reserve.

It’s the sort of place that appeals to me; I grew up near the pine forests at Formby, on the west coast near Liverpool, and I used to go running through the trees along sandy paths while my uncle walked the dog. Here, the paths are either stony forest trails, or, in more sandy areas, wooden boardwalks have been lain down to protect the dunes, at least in the areas nearer Wells.

Heading towards Burnham, the dunes widen, and it’s possible to wander any number of ways through them, all of which felt quite isolated and distant. It might also be a good place to wild camp (as we suggested to a young couple we met in Burnham), though it was still only mid-afternoon when we passed through.

Burnham is a series of small villages, similar in location and style to Cley and Blakeney. They were very much geared up to fishing (and associated maritime activities); indeed one notable resident of the area in his younger days was a chap called Horatio Nelson, later to really make a career out of seafaring. Although we didn’t pass through his birth village of Burnham Thorpe, which is a mile or so to the south of the coast and has a pub named after him, we did have a pint in “The Hero” pub in Burnham-Overy-Staithe, which is also named on his behalf and is full of memorabilia devoted to him.

Day six: Burnham to Hunstanton

Staithe is an old word for harbour or quayside, and there’s a quite a large harbour-front both here and at neighbouring Brancaster Staithe, a little further along. Again, many of the channels here are quite severely silted up now, but it’s not hard to see the extent the influence of the maritime industries would have had around here.

Old fishing vessels in Brancaster Harbour.

At this point (Brancaster village), the Norfolk Coast Footpath veers sharply inland for a large rectangle, down a country lane and along the edge of a field. For reasons known only to itself. We hit this section on a particularly hot morning – take water. It returns to the shore at neighbouring Thornham village (contains a useful couple of pubs to cool off in) and becomes a nice path through and alongside the sand dunes, past Holme-Next-The-Sea, all the way to to Hunstanton. This part of the path also had us passing the most people since we’d climbed Beeston Bump – here though the majority of foot traffic was heading across our path, to the beaches (especially around Old Hunstanton and its obligatory golf course).

The multi-coloured cliffs at Hunstanton.

Hunstanton is noted for its unusual rock formations; indeed the style is named after these very cliffs. My knowledge of geology rivals that of biology, but I can inform you that this is a type section of rock known as the Hunstanton Formation, and it’s the primary example of layered limestone rock, laid down around 130 million years ago. Late-period dinosaurs would have seen this and been as equally bemused as I.

The town itself is the largest place on the path since Great Yarmouth. It’s similar to the other resorts the path passes through, with beaches, cafés, ice cream, arcades, and mini-golf, so has quite a good tourist base and vibe. Indeed I’ve been here several times; I used to be involved in a nationwide social organisation and every year we’d have a meetup in a caravan park here. In November, cos it was cheaper. As if to support this, the path into Hunstanton was lined with much more caravan and holiday accommodation than any of the other towns en route.

Hunstanton Town Centre.

The Norfolk Coast Path technically ends in Hunstanton, on the main Parade at the war memorial, near the town hall. Back at Holme, the Peddars Way footpath heads off pretty much due South, going to Thetford, from where you can get the Angles Way all the way back to Great Yarmouth. We, of course, did not do that. Rather, after a night in Hunstanton, we continued along the coast to King’s Lynn along … by the time you read this there should be a designated footpath that does this route, as part of the England Coast Path, but on our adventure …

Day seven: Hunstanton to King’s Lynn

This day saw our first rain of the hike, which felt a bit rough coming in from the sea. There were puddles on the promenade and the skies were grey as we passed the caravan park where I’d spend many a November weekend with my old social group.

The path exists for around 11km along the coast, as far as Snettisham. The first 4½ km, to Heacham, go past endless, soulless, holiday accommodation. Then the land opens out a bit with wider dune and grass space, dotted with larger tents that make it feel a little like Central Asia, and it feels a bit more remote.

This reminds me of Central Asia – yurt-like buildings in wide open grasslands.

After around 8km, you reach Shepherd’s Point, where there’s a couple of large lakes inland, while mud-flats extend seawards towards Lincolnshire. If you could walk across them, it would have made a useful short-cut for us. However, this is The Wash; a kind of bay that over time has moved around due to sediment changes. It was here that England’s Worst King (John), on the move during one of the many civil wars, is alleged to have lost some of the country’s treasury (including the crown jewels) in the mud.

You may be unsurprised to find though that, because of its location between the two, Shepherd’s Point is yet another spot on the Norfolk Coast Path that’s good for birdwatching. Indeed the lakes are the main part of a designated RSPB reserve, and there’s a couple of large huts here in which you can sit and look out at the birds on the lake. Of which there are legion. Obviously if I knew about birds, this would be a very different blog post.

Lots of birds on one of the lakes at Shepherd’s Point.

South of the reserve, our path became … theoretical. We were tracking routes on the map, but at one point we encountered two rather large metal fences blocking our path, either side of a bridge. The stream it crossed was small, but quite a way down, and a detour would add several km to the journey, so, uhm … Remember, I’m not a role model and you shouldn’t do anything illegal, but it was a Sunday and we were in the middle of nowhere. I’m pretty scared of heights and have little balance, but I somehow made it over with only some bleeding on my hands because I gripped hold of the fence so tightly.

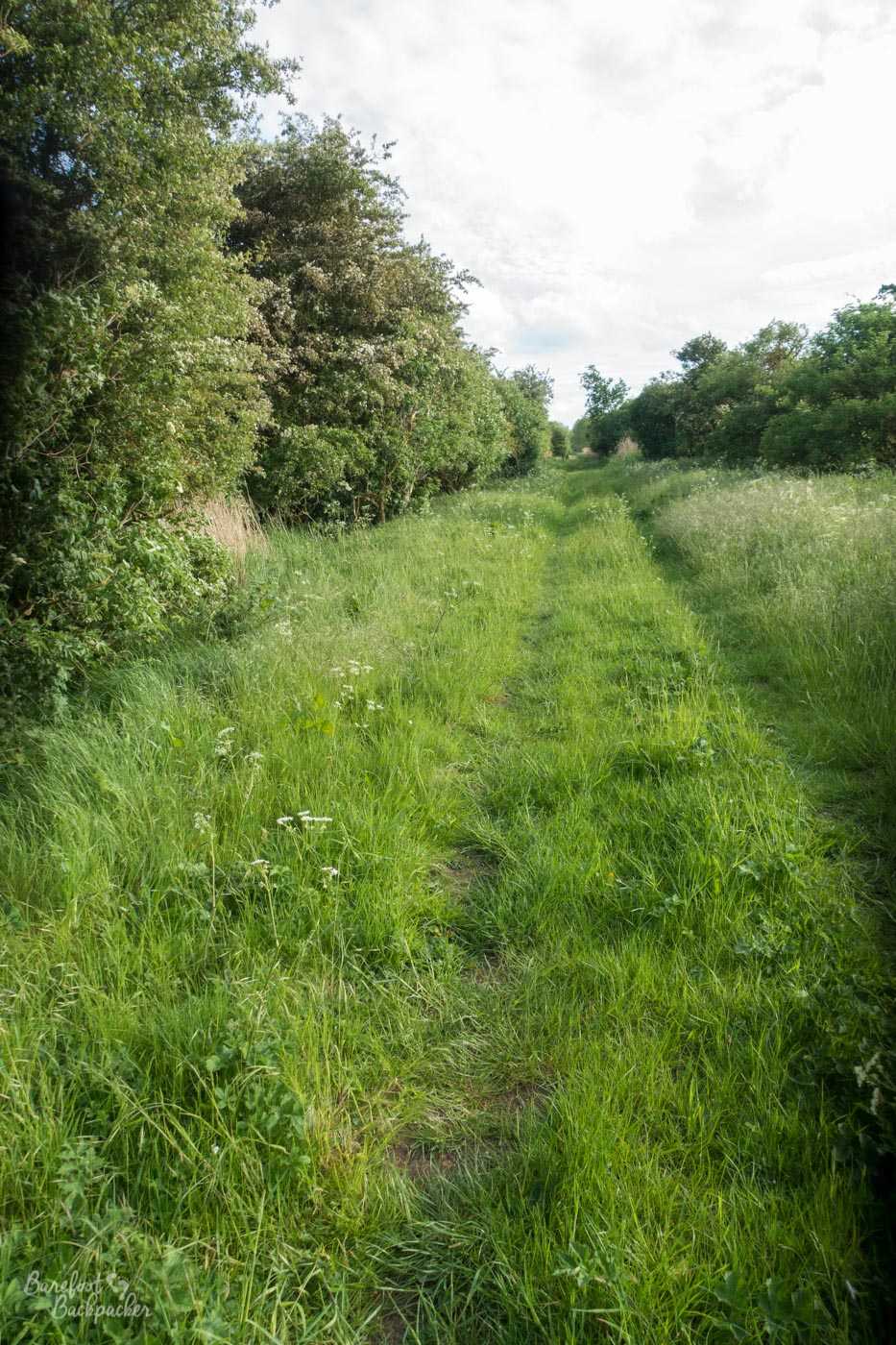

After walking along some country lanes (at one point passing a wood where a deer was surprised by our presence and ran off, much to our own surprise), we thought we’d wander down a dead railway line that pretty much went straight to King’s Lynn. After 1km of a pleasant, straight, flat, tree-lined walk, we reached an empty gap where a bridge used to be. Although not wide, the stream it used to cross was very muddy with no indication of how deep it was. Assessing our options, and realising we weren’t capable of blocking said stream, we turned around and took a trail through a field instead. This led us to another country lane, another footpath, and, eventually, another small stream we could cross manually, albeit by slipping down the bank and then clambering up through some nettles into a ploughed field. Paths? Where we’re going, we don’t need paths.

One of the many somewhat unofficial paths we walked along on the way to King’s Lynn.

Eventually we reached the roads at Castle Rising and had a cooling walk along proper pavements in the mid-evening sunshine into King’s Lynn. We don’t like roads much but this was a bit of a relief.

All of this, by the way, was to avoid a huge detour around the Royal residence at Sandringham, which covers a huge area and is traversed by a major road which we didn’t want to walk down.

Hints and tips for Hiking the Norfolk Coast Path

In general, hiking on the Norfolk Coast Path is, compared to many other long-distance trails in the UK, relatively easy. There’s no major hills, no sections of truly remote countryside, and there are plenty of villages en route, never mind the few sizeable towns. In addition, even the beaches are liable to be populated, at least in part. Some of the long sections in the dunes and wildlife areas might feel a bit quiet, for example around Blakeney, and you might go for a couple of hours without seeing anyone, but this solitude won’t last. That’s not to say it’s ever truly crowded, well except for the sections that go right through the middle of town promenades, but it’s definitely more a path for social interaction rather than, say, the Pennine Way. In our experience too, the people we encountered were generally friendly and more than happy to stop for a chat.

Accommodation on the Norfolk Coast Path

Surprisingly for England, we were mostly able to wild camp, sometimes somewhat more officially than others. This had been our intention for the whole of the hike across the country anyway, although we hadn’t pre-planned any particular spot.

At Caister we found a spot in the dunes, just off the path, in one of the few flat clearings large enough to take the tents. In Happisburgh and Overstrand, we found gardens (one house, one residential home) to sleep in after having conversations with locals in the pubs. Alcohol (on their part) may have been involved in their offers, it must be said.

Near Blakeney and Burnham we set up our tents by the side of the lane right at the edge of the marshes, and quite some distance from the villages. That didn’t stop us being passed at 10pm by birdwatchers, nor at 5:30am by a jogger. Neither were bothered that we were there, even though such wild camping is technically illegal. Again, I’m not a role model.

Our first wild camp, on day one, near Caister. We’d been joined by Joe, our videographer.

Our only indoor accommodation was at Hunstanton, where fortunately a large sports party had cancelled their booking at the backpacker hostel there so they had some room. Otherwise we’d have had to find somewhere near Sandringham to camp out and that would not have been … an aid to restful sleep.

Obviously, if you’re doing this entirely above the law, and without tents, there’s enough towns and villages on the Norfolk Coast Path to easily find somewhere to stay. Indeed by the region’s very nature, accommodation is plentiful, even in the smaller villages like Brancaster.

Food

We tended to grab lunch at cafes or buy from supermarkets along the route, while evening meals we mostly made use of our camping stoves. This was partly because we were hiking the Norfolk Coast Path as part of a much bigger journey so we had the equipment and food anyway.

There’s no shortage of villages and towns on the route with places to eat; even small villages like Mundesley are set up for mostly the beach-loving tourist crowd and have seafront shops and cafes where you can buy breakfast sandwiches and ice-creams. And of course the larger towns like Sheringham have adequate town centres where you can stock up on provisions or just grab a sausage roll and pre-made sandwich. You’re never going to be stuck for a place to eat or drink on this hike.

Pub lunch in Thornham, on the way to Hunstanton. Possibly a place called ‘Chequers’.

We also made copious usage of pubs; I think we went in one pretty much every day on the hike except the very first day, to the extent that some of my friends wondered if we were trying to enact Britain’s longest pub crawl. They were useful places to recharge our electronics, have a break and a relax for an hour or so, and of course take in some local beers. In both Happisburgh and Overstrand, they also served as convenient places to find a place to spend the night, by chatting to the locals and seeing what was around.

Equipment and Clothing

The Norfolk Coast Path isn’t a challenging hike. It’s largely flat, with some undulating sections but nothing you wouldn’t get in an average city walk. There’s only really one hill – Beeston Bump – everything else is sand dune, ridge, or short series of steps. The terrain is mixed. Some sections are on grass, or at least compacted trails through grass. Parts are on tarmac road, while at times the path literally goes along the beach, either sandy or pebbly.

You don’t need specialist hiking equipment – I didn’t use my hiking poles at all, and you certainly don’t need hiking boots (although the frequent gravel and pebble shoreline means it’s not advisable to do the whole thing barefoot – take sandals at least!). That said, this also means while much of it is accessible to most abilities of mobility, it’s not wheelchair-friendly at all.

Barefoot Hiking on the Norfolk Coast Path – here just west of Sheringham.

We hiked in really good weather for the majority of our time, but be aware that it is very coastal (it’s not called the Norfolk Coast Path for nothing, you know!), so it’d be advisable to protect yourself against the wind. If the rain does come, there’s no protection so a good raincoat would also be recommended, just in case. Also one word of warning: there’s very little shade for the most part, so take a hat.

Getting there and away

The Norfolk Coast Path is very well served by public transport as well as road, to the extent that it’d be easy to do the whole hike in sections, using even Norwich as a base. We started in Lowestoft, and both there and Great Yarmouth are very well served by trains and buses. Sheringham and Cromer are also served by rail, whilst Hunstanton has a convenient and regular bus service from King’s Lynn, from where you can connect easily to a train to London.

There are some buses that serve the smaller villages en route, and it’s certainly possible to do pretty much the whole journey by bus, and hike around as you wish. There are other rail services in the area but these are heritage lines catering more for the tourist market than the through-hiker.

By road, the A149 follows the path fairly well, although it heads a little way inland for the Great Yarmouth-Cromer section. That said, there’s enough lanes reaching the coast, and car parks are fairly liberally placed along the whole route, so it’d be trivial to park up somewhere and hike a few km in either direction. Indeed a lot of birdwatchers headed for the Staithes do exactly this.

Summary

The Norfolk Coast path is a lovely, long, but fairly simple path that’d be a great introduction to hiking if you’re new or unsure. Few hills, easy access, and a good mix of terrain make this a perfect first hike. I’m glad we started our hike across Great Britain here.