Indian Pacific – a name, like ‘Orient Express’ (but possibly not ‘Woodhead’) which evokes a nostalgia for times long since gone, a ‘Golden Age’ of rail travel still accessible to the Middle Classes and upwards who’d sooner spend hundreds of pounds on a luxury experience that takes ‘days’ as opposed to a flight for less than 100 bucks that takes a couple of hours. And of course for the truly budget-minded traveller, or for someone eager to reduce their carbon footprint, there’s always Flixbus or Greyhound.

Life-sized sculpture of an Australian Wedge Tail Eagle in Adelaide station; the symbol of the freedom and adventure of the Indian Pacific.

However, I don’t like flying (I find it too cramped, as well as incredibly boring, plus of course you can’t stretch out very much, even sometimes in the exit row seats, unless you travel Business Class), and in any case it’s not very often you do get the chance to ride on such an iconic journey.

The Indian Pacific service runs across the south of Australia, almost (but not quite) the coast-to-coast service its name implies. The route operates between Perth and Sydney, and takes in the region of 65-70 hours. [A flight takes 5 hours and is considerably cheaper, yes.] Also, despite impressions, the Indian Pacific itself is a relatively new experience. Although cross-country rail travel had been possible in Australia since 1917, it was only as recently as 1970 that the full journey could be taken on the same train, as there was no uniform rail gauge in the country. While a story beyond the scope of this blog post, it seems that railway pioneers were as chaotic as as everyone else seemed to be in Australia at the time. So unlike other experiential rail journeys, this one is a designed experience rather than a reminiscent one.

I was lucky to be able to take the journey at all, in a way. When I rode it, in June 2014, there were three ‘classes’ on board – most of the passenger coaches were what are known as Platinum Class and Gold Class. I don’t know what the difference is between the two, only that they both have ‘cabins’ with beds in, which seem similar to what you’d find in first class compartments on European and ex-Soviet Trains. They also had their own dining cars, with proper restaurant service. I, unsurprisingly, was not in that zone.

My view for 41 hours, of a plain blue wall. And, like they’d ever let me into Gold Class.

Rather, I was in ‘Red’ Class, a name that fits rather well with Gold and Platinum, don’t you think?! Red Class was the ‘economy’ service, and consisted of one carriage filled with (business-class) airline-like reclining seats. Although the seat did recline quite a long way back, it still wasn’t as comfortable as lying down. They did darken the carriage for most of the hours of the night, but that’s no different from being on an aeroplane.

Inside the Red Class carriage. Nothing special.

There was also a small place you could buy food – a small kiosk at one end of a carriage of tables. It was actually pretty functional, offering chocolate, nuts, pasties, and crisps, as well as doing proper lunches and evening meals; not much choice, but the food wasn’t all that bad.

Given how long the train was, and how many other carriages there were, we were very definitely the odd ones out. A couple of years after I took the trip, they removed Red Class completely as it was deemed ‘not a financially viable service’.

East Perth Railway Station – see how long the train is! Most of it is for posh people though …

I took the service Eastbound, from Perth to Adelaide. I was sat next to a chap (also called Ian) who was going further than me, to Canberra (via, I think, Melbourne). He preferred the train, he said, he found it more relaxing, less stressful, and as he was retired, time didn’t have as much of a hold on him. He also said train travel was pretty good value for money for retired people, and he’d taken the train to Perth only about a week earlier.

It departs from Perth East railway station, which when I was walking to it felt like an awful long way out the city centre and over a couple of several-lane highways but when I looked on a map for the purposes of writing this article, it really isn’t that far and I was probably just feeling stressed and lethargic that morning. It was a Sunday, and I hadn’t eaten much. The station is in a largely residential area though, and there’s not much of convenience in the immediate neighbourhood, so bear that in mind.

An old steam engine and train carriage, at East Perth railway station.

One thing Perth East station does have though is a couple of railway exhibits; replicas/models of trains from the early days of steam to a modern TransPerth suburban commuter train. East Perth is also the terminus to one of the longer regular regional rail routes I know of, to Kalgoorlie – 650km, takes 8 hours, runs once a day. Still not really commutable, it must be said. That service is called the ‘Prospector’; there’s nothing special about it, it just has a meaningful name (Kalgoorlie is famous for gold mining), in the same way the train through my hometown of Kirkby-in-Ashfield is called ‘The Robin Hood Line’.

One of the reasons it takes 8 hours, by the way, is because, just like the Trans-Mongolian/Siberian railway, the average speed of the train is pretty low (not far either side of 50 kph). A little looking either side also revealed that much of its length so far is single-track; we kept pulling into sidings at ‘stations’ to let freight trains through.

Kalgoorlie was the first stop out of Perth on my trip, in fact. It’s not a place I know an awful lot about, save it’s one of the largest cities in the world – by area, I hasten to add, not by population, which stands at around 30,000, the vast majority of whom live in the Kalgoorlie urban area. The rest of its 95,000km² (an area between that of Hungary and South Korea) is almost completely uninhabited.

Statue of and (replica) memorial fountain to Patrick Hannan, who discovered gold here in 1893 and is credited with finding the town.

The city is most famous (not only for Kevin ‘Bloody’ Wilson but also) for the gold mines that are the only reason for the town’s existence (as no-one in their right mind would build a sizeable town on the edge of a desert like that). For an extra $80 (AUD) I could have taken a tour of the largest of these gold mines, but I was content to save my money and have a walk around the town.

The main street of Kalgoorlie; shops and a very ornate pub.

At this point I ought to mention we arrived there at around 11pm and we’d be stopped there for at least two hours. On a Sunday evening. Pretty much nothing was open and there was virtually nobody else around. (I doubt the gold mine would have been much different. Anyway I wasn’t dressed for mining; they probably object to bare feet on health/safety grounds, even in the visitor centre.)

Kalgoorlie itself seemed a compact town predominantly built in a grid pattern, and the high street gave an impression of being quite ‘wild west’-like, with the way the buildings looked. It would be easy to imagine cowboys fighting in busy bars while sheriffs looked on helplessly. And to be fair, although it didn’t have cowboys, it certainly had a similar kind of (negative) reputation as towns did in places like Oklahoma and Wyoming, with banditry, prostitution, and gambling.

A hotel in Kalgoorlie. It’s easy to imagine it’s seen some things, but inside and outside its walls.

Beyond Kalgoorlie, and into day two, the train headed onto the appropriately-named Nullarbor Plain – a large area of very dry scrubland at the southern edge of the desert. Its name comes from the fact there are no trees on it. It’s not like the Gobi or Aralkum deserts; the line doesn’t go for hours through nothing but sand or rock, but rather passes endless vistas of hardy bushes living an extreme existence in a very arid sandy soil – localities here get on average only a quarter of the annual rainfall that Nottingham does.

The Nullarbor Plain. Flat, scattered small short shrubs amid dusty yellow/orange sandy soil, under an unforgiving blue sky. For a day.

The plain is crossed by the rail line and one main road; along the latter is what’s often regarded as ‘the world’s longest golf course’ – a full 18-hole affair using some designated holes on pre-existing courses, with specially-constructed tees/greens at roadhouses en route. The distance between the first tee and the 18th green is some 1,365km. I’d imagine there’s a lot of bunkers to avoid too.

The Nullarbor Plain is also the location of the longest stretch of absolutely straight railway line in the world (some 480km). But then I guess on a vast treeless plain, there’s no real need to have bends in a line.

Oh look, a signpost.

What the Nullarbor does have, perhaps surprisingly, is (dead) railway stations. Some of these served long-forgotten villages that existed purely to serve the railway itself, others provided a link to farmers who lived out here. Freight trains acted as a kind of mobile delivery service, dropping off goods to these small hamlets and picking up mail etc; the main road that cuts across the plain is about 100km to the South so these trains were pretty much the only link these villages and farms have to the outside world.

In previous decades there were more actual villages with people living out here, but once the railway had been privatised and the rail company no longer needed to be serviced by these towns (instead being able to source all provisions necessary from elsewhere), most of them closed. Pretty much the only people out here now are farmers. The former stations merely serve mostly as sidings where freight trains can overtake/pass by the passenger service. At most of these ‘halts’ it’s often not easy to see even why the station was ever there – there’s no trace of a village in sight and the plain is pretty flat.

Just beyond Cook Railway Station, looking west. Note the lack of … well, anything.

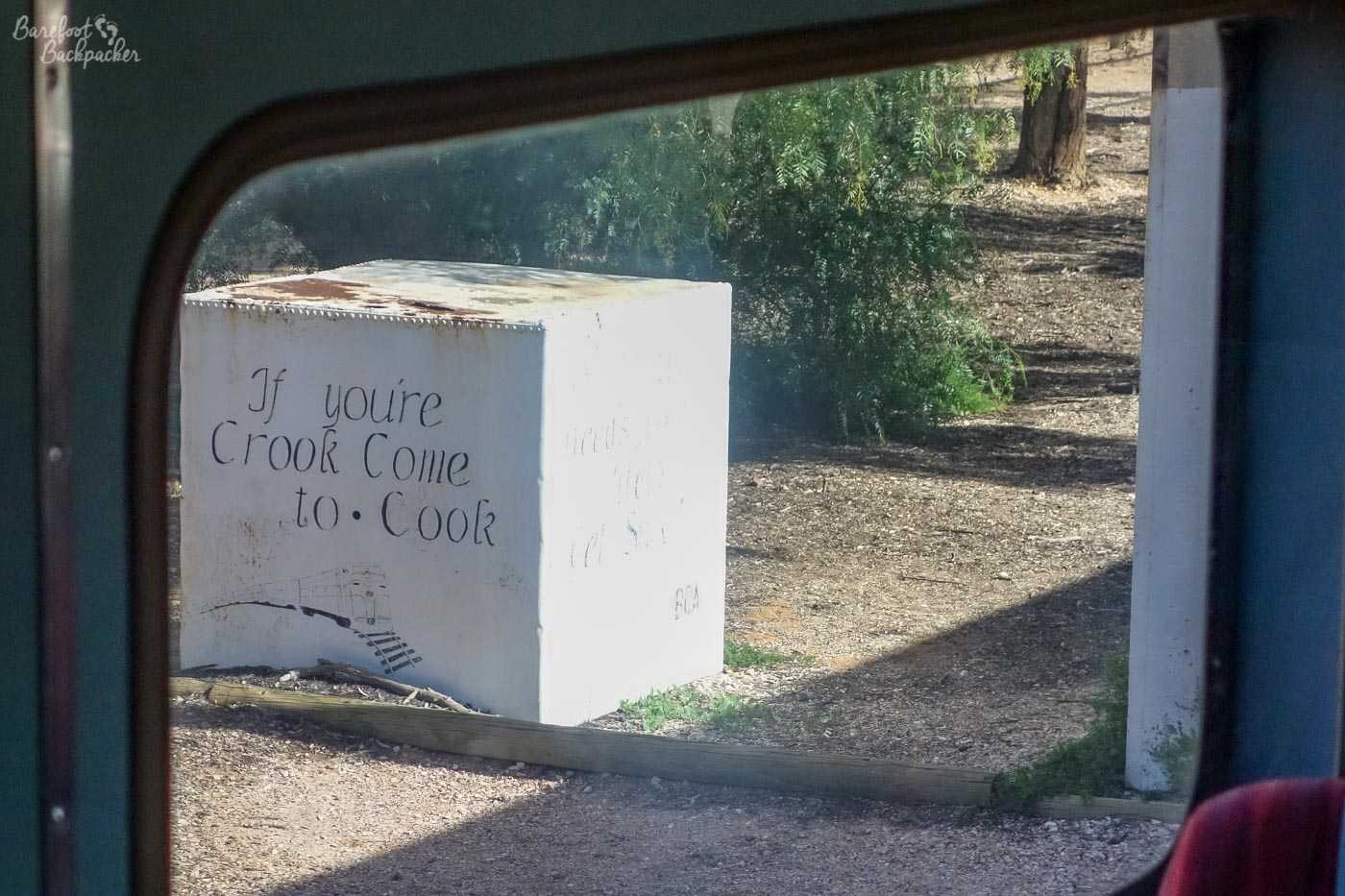

One such station that is still used though is at Cook. It lies close to the state border between Western and South Australia (although in the latter, it uses both time zones for convenience). The train tends to stop here for half an hour or so – partly to refuel, re-water, and to provide an opportunity to change the rail crew, but mainly for the simple fact of breaking the journey. One team of train crew drive/service the train through Western Australia. They’ll then leave at Cook, have a rest and sleep, then take charge of a Westbound train heading back to Perth. They’ll relieve a South Australia crew on that train who, after a rest and sleep, will take charge of the next Eastbound train back to Adelaide and Sydney.

Well-kept houses in Cook. Pretty much the only buildings that appear well-maintained; assume they’re still lived in, or at least where the crew overnight.

At its height it was a large village of maybe 25-30 people, and had a jail, a hospital, and a school. Most of the inhabitants were employed to service the trains and the railway line itself, but over time with increased efficiency of the railway, the population has dropped to about 4. Much of the town is thus a ghost town, but one with buildings and facilities still in situ, including a cricket pitch.

Cook cricket club, apparently.

Painted sign, advertising the fact the village had a hospital.

Although mostly empty (and bits of it are falling down) it was quite easy to see where the village is/was, though it was clear that it was never a large settlement; half an hour was plenty of time to get from one end of the place to the other and have a good feel for the place.

In earlier days this would have been a hive of activity and refreshment. The ‘memorial’ btw is to Murray Sims, a railway worker of 28 years who died here in Cook.

That said, we were ‘encouraged’ to walk quicker by the vast hordes of annoying flies that got everywhere. As soon as we stepped out of the train, we were harassed by packs of the things. Although they weren’t much of a bother whilst walking, as soon as we stopped to take a picture they all came crashing down on us – we felt like we were covered in them. It made being out there quite uncomfortable.

Cook Railway Station. It’s seen better days, yes.

From Cook the line slowly curls round towards Adelaide. We had a further stop at Port Augusta for two hours, but that was in the middle of the night so nothing much happened. We reached Adelaide pretty much on time (about 7.20am); I mean that’s a far too early time to be properly checking-in or anything, even to a hostel, but it did give me a free bonus day to explore Adelaide city, at least. The station’s a couple of km outside the city centre but it’s a pleasant walk; plus at the time, that I was in a new city had given me a bit more of a spring in my step.

The whole journey from Perth had taken somewhere around 41 hours, including two nights’ sleep. There are easier, quicker, and cheaper ways of getting between the two cities, and I have to say if I ever need to do this journey again, I will fly. I mean, it’s probably a nicer experience in Gold Class, but that’s I guess not quite how I personally roll.

Adelaide Parklands Railway Station – my terminus, at least.

That’s not to say I don’t regret the experience. It was a fascinating journey and I’d always been keen to see the Nullarbor Plain especially, because it’s one of those weird once-in-a-lifetime trips that you take every now and then. I’m definitely glad I did it, and I’d’ve regretted it if I’d had the opportunity and declined it. Plus I do really like train journeys in general – it’s very much my preferred way of travelling, and I do take them wherever possible, especially overnight ones (it’s a cheap way of spending the night, plus on trains with beds, I do at least get a decent sleep).

I’m just not convinced I’d do this journey again.