It’s hard to talk about Africa and not mention colonialism; its effects down here in Southern Africa were a bit different to in West Africa, but that’s not to say they were any less harrowing – indeed colonial rule saw a long-term legacy through the Apartheid regime in South Africa.

Zimbabwe is one of those many countries created by colonialism, whose borders were created as a result of meetings in smokey rooms rather than out of any concern for what was the real situation on the ground. The post-colonial history of Zimbabwe is complicated, involving people at both extremes of the racial divide, but it all started with an archetypal white British Christian male so beloved of The Empire.

But before we get onto all of that, let’s talk about a scenic and hilly region in Southern Zimbabwe known as the Matapos, or Matabos.

Part of the Matapo Hills, with the rocks creeping out from between the trees.

Bulawayo is the second city of Zimbabwe, and lies in the SW of the country. It’s a comfortable overnight train from Victoria Falls – one of those journeys that backpackers love, being cheap, traditional, and surprisingly pretty comfortable, albeit very basic. I shared a first-class cabin (the ticket office in Victoria Falls town refused to sell me anything less) with a couple of other backpackers exploring southern Africa, and while disappointing I wasn’t on my own as happens a lot in Central Europe, it’s always interesting to meet with fellow travellers ploughing their own furrow through the world. The journey there was slow but perfectly acceptable – before the sun set we strolled through the bushlands and it would have been a great place to stop and seek out more wildlife, though of course the sound of the train would have scared everything off for some miles around. As an aside, the dining car wasn’t open; we were told it was because ‘it only operates northbound’.

The train from Victoria Falls to Bulawayo. We were sat at the very back.

We were staying at the same backpacker hostel, albeit in different rooms, so we caught a taxi as it was about 6km out of town. Now, I know I try hard to not overly-revel in my colonial white privilege, but there’s certain things in pop-culture we’re brought up with that even a worldly-wise traveller like myself can’t help but squee at. And the concept of riding in the back of a pick-up truck, sitting on a metal bench welded to the floor, open to the world, through an African town, is just one of those things that appealed to 8-year-old me. Like something out of a dodgy 1950s movie.

Anyway, I digress.

The Matapos are a range of hills in southern Zimbabwe that are now encompassed by the Matapo National Park. They’re a bit of a drive to get to – it’s a taxi or tour from Bulawayo as there’s no public transport – but definitely worth the adventure. Apparently it’s possible to view wildlife there, but that wasn’t why I went, and in any case I’d already had my fill of wildlife in Southern Africa. Rather, the Matapos are incredibly scenic, as well as encompassing several thousand years of history.

Part of the Matapo Hills.

Well, even longer than that really. Several of the stopping points of a trip around the Park are to caves where you can see what remains of some old cave paintings, for example at Pomongwe Cave. There is a rumour that some of the paintings here were done within the last two hundred years as a means to draw people to the area, but it cannot be denied that the region has been inhabited since the earliest days of Homo Sapiens – indeed, a site known as the ‘Cradle of Humankind’ (where Hominid remains, some dating over 2 million years old have been found) lies not too far South, in the north-western part of South Africa. Therefore, regardless of the authenticity of these specific cave painting, there are genuine remains of ancient humans scattered all across the Matapos area (indeed, across Southern Africa in general), covering pretty much the whole history of humanity from iron-age-era San (bushmen) all the way back to evidence of Homo Heidelbergensis some 300,000 years ago.

Example of some of the cave paintings – they seem remarkably clear for something allegedly so old, yesno?!

My problem with cave paintings is that, a bit like pizza (*), the idea of them is often more interesting than the reality. In my head, I’ve been accustomed to believing they’re comprised of drawings that clearly represent humans hunting the local wildlife, and it makes you go ‘wow, that’s history right there’. In reality, you walk up to a sandstone rockface and peer at it, looking for telltale scratches or marks that indicate something that someone thinks represents a spear, or an eland or kudu. I’m not much good at pattern recognition at the best of times; that, plus my lack of knowledge about biology and nature, means that cave paintings kind of leave me a bit bewildered, I have to say. I also can’t visualise the difference between eland and kudu.

(* I find pizza boring. Sometimes I crave it, and it looks really good, but then I eat it and go ‘eh, snore’. And when I’ve finished I think, you know, I’m still hungry. Don’t @ me!).

More examples of cave paintings – these are a little more faded.

[As an aside, I live not far from the most Northerly ice-age-era cave paintings ever discovered.]

A commemoration of something much more recent is present not far past the entrance to the park; there is what amounts to a war memorial dedicated by and to the Memorable Order of Tin Hats, or MOTH. The ‘moths’, as they’re known, are a veterans’ organisation primarily to remember and support those who fought in conflicts on behalf of South Africa, although membership includes those who served in wars alongside (or indeed, against) South African forces; this includes soldiers from other colonial and post-colonial states in the wider region. This particular memorial, for instance, is dedicated to those who fell in service in World War Two, primarily serving the British colony of Rhodesia. It’s made up of a couple of commemorative plaques and stones, and a small remembrance area. In some ways it feels out of place here in the wild countryside far from any battles, and yet it brings home just how all-encompassing the war was, and how many nations and people from different origins took part.

The MOTH shelter – complete with dedications – where people can go for quiet reflection and remembrance.

The most important aspect of the Matapos though is that they’re sacred to the Ndebele and Shona people; it’s been their home since time immemorial. It makes it all the more weird then to stand in one of their most sacred sites (World’s View), at the top of a hill overlooking much of the plains of southern Zimbabwe, and realise that just a few steps to your right is a flat gravestone, inscribed with a memorial to a 19th Century white British colonialist.

Yes, that’s what I thought as well.

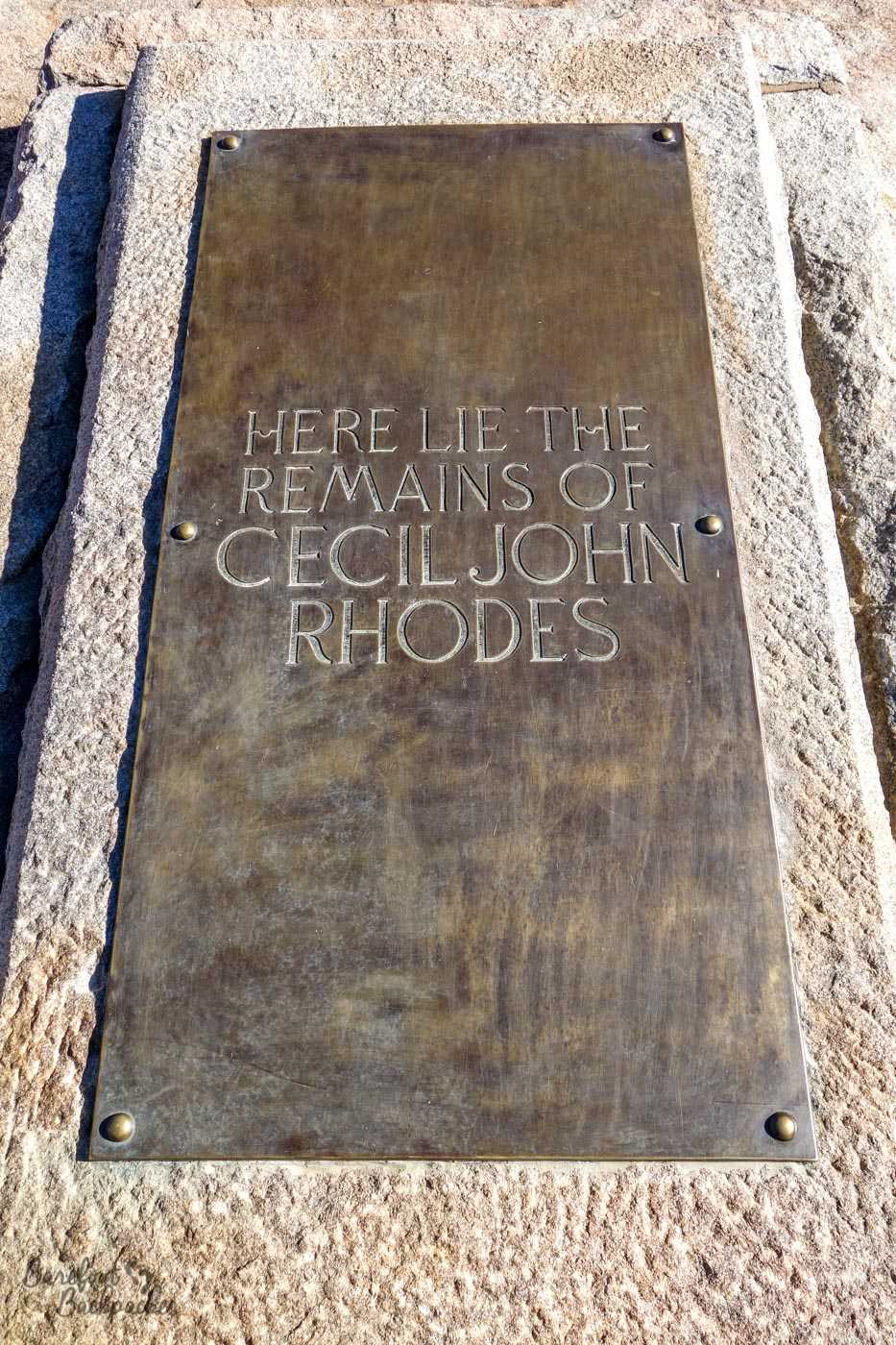

The grave of noted colonialist Cecil Rhodes.

At the time of my visit, there was a bit of controversy about Cecil Rhodes – more so than usual, I mean; there were movements in neighbouring South Africa to remove his statue from college campuses. In Zimbabwe, however, he’s often lauded as the founder of the state, and without whom the Zimbabweans fear the colony would have simply become another province of South Africa.

However, as an introduction, let’s make no bones about this. Cecil Rhodes was a typical middle-class white British male. And by ‘typical’ I mean ‘nationalistic’ and ‘racist’ – not in an outwardly aggressive BNP-like way, but more in that his entire world view didn’t acknowledge being any different. A famous quote of his was telling Lord Grey, the then-Governor of the British Cape Colony: “You are an Englishman, and have subsequently drawn the greatest prize in the lottery of life.”. Quite mild and jingoistic, nationalistically harmless, right? Well, the scholar Bernard Magubane quotes him as saying “The native is to be treated as a child and denied franchise. We must adopt a system of despotism, such as works in India, in our relations with the barbarism of South Africa.”. Which is a little more … the phrase ‘white supremacist’ has been bandied around by later historians and cultural commentators, yes.

The son of a vicar, he was sent to Southern Africa for health reasons in his late teens, and quickly became the owner of a diamond mine – as one does, I guess, on an average gap year adventure. He entered parliament in Cape Colony at the age of 27, and had become Prime Minister ten years later. He doesn’t seem to have been a particularly good Prime Minister – the majority of his policies were geared towards the expansion of the British Empire rather than maintaining the integrity of the colony itself, which culminated in him pretty much single-handedly causing the Second Boer War.

His main domestic legacies in Cape Colony were largely ethnocentric; they included the dual policies of considerable increase in the property requirement to vote, as well as restricting how much property certain segments of society could own – this pretty much completely disenfranchised the black population of the Colony. He was also responsible for breaking up the traditional concept of land ownership in the first place, ensuring that much more of the land was owned by (rich) individual (white) settlers, which could then be used to increase industrialisation, funded by the same cheap workforce (blacks) who’d been kicked off the land in the first place. In a very real sense, Cecil Rhodes could be seen as the ‘Godfather of Apartheid’.

Which does of course raise the question – what is someone like him doing buried in a part of a majority black country, which is considered sacred to the local tribes? The answer lies in his relationships with the local tribal leaders in the areas to the North, beyond the control of Cape Colony itself, and in his desire for the British Empire to dominate, above everything else.

Statue of Cecil Rhodes, in Cape Town. Picture taken by KNewman1 / CC BY-SA

The areas now known as Zimbabwe and Zambia was run, not by a colonial government nor directly from London, but rather through a Company (the British South Africa Company), which although not directly part of Cape Colony, was still headed by Cecil Rhodes. Their remit was, pretty much, to ensure as much native land as possible saw London as their natural … ‘protector’, for want of a better word, rather than see them be subsumed by the Belgians in the north, but especially the Portuguese in the West and East. To this end, the Company made certain promises to the local tribal chiefs regarding land and mineral rights, in return for lordship over them. That these rights were incredibly disadvantageous to the chiefs and pretty much ensured white economic rule for the foreseeable future only became clear to them in hindsight; in the short term his offers were seen as being better than the alternatives (of either being ruled directly from Cape Colony, or worse, conquered by the other European powers) – in addition he endeared himself to the local tribes when at one point, during negotiations to end a war with the Company, he very purposely sat with the tribal chiefs at the negotiating table rather than with his fellow whites, in an effort to show a certain solidarity with them.

His promises and actions endeared him with them, and as a result the local tribes held him in much higher esteem than pretty much any other white settler, farmer, miner, or politician. When he requested that he be buried at World’s View, the Ndebele people were only too happy to oblige.

Also at World’s View is this memorial to a patrol of British soldiers killed by the Ndebele during the First Matabele War; Cecil Rhodes, in ultimate overall command, requested they be re-interred near, and a memorial built to accompany, his grave – again showing in just how much esteem the Ndebele people held Rhodes in.

Today, there are some within Zimbabwe who see him as a colonialist, racist, and someone who shafted the native tribes out of their material wealth, and press the UK government to repatriate him, but the Ndebele still stand firm, seeing him as in important part of Zimbabwean history, and someone without whom the country would be a very different place, if indeed it had existed at all.

Incidentally, the area the Company controlled ended up being called Rhodesia after him, within his lifetime even, but it wasn’t the name he chose; he preferred ‘Zambesia’ as it covered land either side of the Zambezi River. Rhodesia was just the casual name the white settlers called it, and it kinda ‘stuck’. Administratively it was subdivided into Southern, North-Western, and North-Eastern Rhodesia – the former became Zimbabwe, while the latter two merged (into Northern) and later became Zambia.

Regardless of how he’s perceived, he’s still a racist though, and doing things to benefit yourself and your kind is still highly nationalistic, regardless if they unexpectedly help people along the way as a side-effect. Also, Adolf Hitler seems to have regarded him as an inspiration, which … kind of tells you all you need to know. Presumably, so did that other noted WW2 imperialist Winston Churchill (who would have indirectly served under him during the Second Boer War).

—

Like this post? Pin it?

Visited: 4 January 2016