My friend Laura and I decided to move to Glasgow. As a pair of financially solvent adults with steady jobs, who are grown up enough to know how to handle basic household maintenance and bill paying, entering the housing market and finding a flat in Glasgow shouldn’t be too much of a problem, right? Famous last words.

Me and Laura: pic taken in 2019 in Philippines.

Letting Agents are the Doorkeepers of Hell

It is important to bear in mind that I was looking during what purported to be a relatively restrictive Covid lockdown situation, even if by the time I started, even Glasgow had dropped at least one level. In addition, I was mostly looking from my room in Sheffield. Remember, Sheffield is a long way from Glasgow – though possible in a day trip it’s not really advisable too regularly without being permanently knackered, so I wasn’t really in a position to go flat-viewing at a moment’s notice. Therefore, you’d have thought virtual and online viewings would be, well, not just offered but preferred, indeed possibly obligatory.

No-one appears to have told the letting agents. Most of them had a policy of ‘you can’t apply for the flat unless you’ve physically visited it’ and ‘no we’re not offering online viewings’. One letting agent told us later this was actually contrary to the Covid regulations that were in place at the time in Glasgow, and was not happy his competitors were doing that, but by then we’d probably have taken a shed.

In addition, much of the time, the viewings were all arranged by the letting agent only on one day. Which may make sense if the flat was currently tenanted, but most of the ones I was looking at were vacant. The first flat I wanted, I had to get a friend to visit on my behalf, purely to satisfy the requirement that we’d done a physical viewing. The day that the viewings took place also seem to have had no relation to when the flat first came on the market; some places had lettings that day, some for one day later in the week, and some … it took about two weeks to get a viewing, suggesting that they were just waiting around for enough people to express interest in it to make it worthwhile getting someone out to give viewings.

And this was another odd thing – there was no real consistency to how these viewings were conducted. In some places the letting agent rep met me at the property and showed me round. In others the rep stayed in one room and I was free to explore. In one flat the rep stayed outside the property ‘for Covid reasons’. Yet the simple idea of just going around the flat on, say, a video call, seemed alien to them, despite it being much more efficient and certainly much safer, covid-wise.

Some of the letting agents were remarkably overworked and understaffed, and I know the housing market (especially in the West End of Glasgow) is very busy at the moment, but that’s not an excuse for basic customer service failures. My VA was doing a lot of phoning around agencies on my behalf. One of them appeared to be completely scatterbrained, having lost paperwork and e-mails, not really knowing what anyone else working there was doing, and generally were a pain to work with, Another, who shall rename nameless, mainly because I can’t recall their name, only that they were based in Bearsden, literally put the phone down on her when she was enquiring about a flat (‘it’s gone’ was the brusque response), which would have been bad form anyway, but doubly so given that was not the flat she was enquiring about. (‘oh that’s gone too’ she was told, snappily, when she called back). Mind you, at least she made contact – a couple of agencies pretty much ghosted her after a while, not responding to e-mails and not answering the phone (all her calls were redirected to an answerphone). Additionally, a couple of promised callbacks she was expecting just never materialised. Imagine being ghosted by a letting agent. I suppose that prevents the need to ask ‘your place or mine’.

A street of tenement blocks in Glasgow, complete with ‘to-let’ signs.

Now, there’s a lot of hate online against landlords. And, is true, there are a fair number of dodgy landlords, out purely to make a quick buck and don’t care about their tenants. But I think much vitriol needs to be levied at the letting agents who act on the landlords’ behalf. I can see why you’d use a letting agent as a landlord; it’s the same reason I hired a VA – because I don’t have the time or spoons to handle the admin, so I’d rather pay someone else to look after it on my behalf. But when the agents act as unilateral gatekeepers, a law unto themselves with no rhyme nor reason for the way they act, when their behaviour is unmoderated and unregulated, contravening government guidelines and breaking all rules of customer service, it really doesn’t put the industry nor the whole process in a good light.

That’s not to say landlords won’t take advantage of the situation. If you know your tenant will find it hard to find other places to rent, because of time, money, or logistical reasons, and they’re likely to just stay in place and not bother finding somewhere else to live, you effectively have a captive audience. This means whatever you want to charge, they’ll likely pay it, even if it pushes them deeper into poverty, because they have no choice. Whatever restrictions you put on what they can do in the property, they’ll likely have to accept, because the alternative is homelessness. And obviously the more the landlord squeezes the tenant, the less ability the tenant has to move. There is even potential here for less legal situations and possibly even abuse – physical, psychological, sexual; if the tenant is someone who needs to be in the property and will do anything to stay there, it would be so easy for a landlord to take advantage of that fact.

You’re not married? Oh, that’s awkward

All of these issues with regards to flat viewing are just the first step in a series of issues that I have to say I didn’t realise existed in the rental portion of the housing market. The main problem, I discovered, is the sheer finance involved in renting.

Laura is an ex-student and can’t prove any income. Now, under normal circumstances I can understand landlords being reluctant to take on someone like that without financial safeguards, but, get this, she’s not paying the landlord the rent. I am. And I can afford it on my own. If I were looking for myself, if I were the only person living there, this whole process would have been really simple and easy. But because she’ll be living there too, it seems she needed to be listed as a co-tenant, and therefore go through the same checks that I do, as if we were ‘equals’. The problem here is this meant she, and therefore we, needed a guarantor to ensure that she would (nominally) pay the rent.

And here’s the rub. I realised that even I, with my background, know very few people able to act as guarantors – homeowners who earn a certain salary. That’s the sort of thing people come to me for (as you may know, I own a house myself. I don’t live in it because my lodger kicked me out, in effect, but that’s not the point.). Ironically, I could have been a perfect guarantor for my friend, only I wasn’t allowed to be because I’d also be living in the property.

We managed to secure the flat only by putting up three months’ rent in advance, *and* a double-deposit. There are very few people in the rental market who would have that amount of money just resting in a bank account, which again means the entire industry appears to be built specifically to fight against those people who need it most. I’d imagine students (who several of the letting agents were actively marketing against) would actually be pretty ‘good’ prospective tenants in a sense because they could call upon the Bank Of Mum And Dad to act as guarantors or deposit-providers. My parents are retired or semi-retired.

It feels like the whole system is set up against flatsharers, passively discriminating against single people, asexuals, aromantics, and people for whom friendship is the primary form of family. Rather, everything is geared towards families. Part of this may be cultural; flat-sharing is ‘something only students do’, or at least young people in communal environments. That is to say, both the fact of flatsharing and the marketing of it is geared towards a specific demographic, and people get irked and confused when a mid-40s man (or at least male-presenting) and early-30s woman, who importantly are not in a relationship, decide to share. Indeed we were rejected by the landlord for one property precisely because of this, because we weren’t a couple, because they felt two people in a relationship would be more ‘secure’ and less likely to break up than two friends. I mean, I could at this point quote divorce statistics, as well as the fact that as long as they still got paid it shouldn’t really matter, but in all honestly that particular flat wasn’t the highest on my preference list anyway.

My friend Kirsty on her wedding day. They are still married, yes.

This led me to assume that even if I were a multi-millionaire earning 250 grand a year, we’d still have needed to either find a guarantor or pay a couple of months rent in advance. It got to the stage my VA was almost tempted to claim that me and Laura were a married couple, just to make things easier. I’m not convinced they’d have ever asked for proof, though it might interfere with her Bumble-ing.

In addition, while regulations exist across the whole of the UK regarding ‘Houses of Multiple Occupation’ (a place where members of several different households live and share facilities), in Scotland particularly these are more strict – properties with three or more different households must be licensed and the landlords vetted. While this is good from a safety and security point of view, and means that the days of shared student accommodation of the kind stereotyped and ridiculed in 70s/80s pop culture should be long gone, what it actually means is that many landlords don’t register their property, thus preventing more than two people sharing in the majority of locations. Had me and Laura want to share with a third friend, our options would have been severely limited.

Houses are for Ordinary Families

My ‘needs’ are minimal. But my desires are limited by the fact one-bedroom houses do not exist, especially not in areas I can afford (and be willing) to live in. If I can afford a 3-bed suburban semi, why should I have to live above a shop in a council estate? Plus, by being able to afford more, why should I be forced to live in somewhere better suited to other people (in both directions)? There seems to be a feeling amongst home builders and town planners that ‘suburbs are for families’ – nay, housing in general is for families. Let’s relegate single people to either grim dodgy flats with peeling paint and threadbare carpet accessible through gun-proof doors next to chippies in strip-malls, or high-quality city centre tower apartments, often by a waterfront, whose annual rent is often more than half the average gross wage.

In fact, I’d suggest British society is, and has been since I was a kid anyway, focused on the ideal of ‘you grow up, you get married, you buy a house’. We have almost an obsession with home ownership, almost to the point it’s become a cliché – this is particularly seen in the way certain newspapers frame their articles, and in the way people react to social events. ‘Will it affect my house price?’ is the dominant theme, especially in what you might term ‘Middle England’. A lot of, particularly English, culture is centred on this concept, from building new houses in the same area all the way to immigration, everything is ‘not in my back yard’, in part because ‘it’ll affect the price of my house’. I’ve never quite understood this, since if house prices everywhere keep increasing, you’ll never get the benefit unless you downsize, and as mentioned, smaller houses are fewer in number. In addition, certainly when I was growing up, there was a much-touted phrase ‘Every Englishman’s Home Is His Castle’, which, amongst other things, reinforces the ideal that you should own a house, rather than rent one off someone else.

And don’t even think of ‘dropping out’ of the market entirely. There’s some tolerance for canal boats, presumably partly because it’s seen as quite a middle-class activity and many residential boats are in leafy quiet suburbs, and partly because large marinas are stable and ‘out-of-sight’ of the majority of homeowners, on the edge of small towns, but anything else is severely disparaged, and even legally restricted. Vanlife is becoming popular amongst younger digital nomad types, but the rules and regulations around it are quite onerous – you can’t just park up anywhere and settle down as many car-parks and lay-bys etc have rules against overnight stays. Also some places may have a(n unofficial) limit on how long you can stay in one location, meaning you’re going to be constantly on the move. There are also be administrative/logistical problems in not having a permanent address, often related to legal documentation and access to certain services etc (think how many things you do that require proof of address), including basic healthcare services.

Lucy (from Absolutely Lucy) sitting in the doorway of her live-in van.

It is, of course, much easier as a single person in a van than if you’re part of a whole community, however. The most affected are the “Gypsy, Roma, and Traveller” communities. As described on The Traveller Movement website (https://travellermovement.org.uk), these are “minority ethnic groups that have contributed to British society for centuries. Their distinctive way of life and traditions manifest themselves in nomadism, the centrality of their extended family, unique languages and entrepreneurial economy.” It’s estimated there are around 300,000 people who identify as a member of these communities, but due in part to their nomadic nature, they’re under-reported in the census so true figures may never be known.

Pretty much nationwide, the Traveller Community faces cultural and social restrictions, backed up by certain legal provisions. You’ve almost certainly seen the news reports about them. The desire from government seems to be to take these people and force them, or at least make them feel like they have no choice other than, to move into permanent (fixed) buildings, probably the cheapest, dourest, housing that the council has available. This is the point where the cultural obsession with housing, and the insularity of homeowners, becomes discriminatory and racist, and where media like The Daily Mail really key into their audience.

The Rising Costs of Homes

We used to have large council estates; whole suburbs of housing owned and maintained by the local council (government) who charged their tenants a relatively low rent for living there. But in the 1980s, the Conservative government at the time operated quite Libertarian views and believed that everyone should have the right and the ambition to own their own homes, so they instigated a policy of allowing council tenants to buy their houses at a discounted rate. By 1991, over a million people had taken advantage of this offer.

The effects of this were severalfold, but socially one of the strongest was a growing feeling amongst those now ‘privileged’ enough to be homeowners that renting was something that ‘poor people’ did; that, along with other Libertarian policies like promoting car ownership rather than reliance on public transport, created a kind of rift between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’. If you rented, you started to be seen as ‘inferior’, ‘easy to push around’, ‘not privileged’, and therefore became a largely ignored underclass.

That these houses were sold quite cheaply relative to market value also led to this divide growing over time. It meant when these houses were later sold on via the private market, they did so at much higher prices (house prices have increased on average by 6.9% year-on-year since 1980, and even ‘crashes’ in the market like in 2009 have, overall, been mere blips rather than substantial reversions). The volume of cheap housing stock dropped, making it far harder for people to buy property in the first place. This hit the youngest generations the hardest of course, forcing more of them into the rental market. Stats suggest that while around 30% of 16-24 year olds in 1980 were homeowners, this dropped to 10% by 2010.

A typical street of what I assume to be ex-council housing as it’s close to the Coxmoor Estate, in Kirkby-in-Ashfield, Nottinghamshire, England.

Interestingly of course, rents are generally higher than mortgage payments, sometimes quite substantially so. As an example, the flat I’m currently renting in Glasgow was on the market for £1,050/month. If I wanted to buy a flat here, it would cost around £170,000, and my monthly mortgage payment would be nearer £600. The gap is much smaller back in Nottinghamshire, because it’s a far cheaper area, but still the gap exists. One of the biggest issues with the housing market here then is: if someone can afford to spend £1k on rent, why would they be rejected for a mortgage if they’d only end up paying a little over half that? ‘Oh but we don’t have long-term security’ – bollocks. No-one has long-term security and whether it’s rent or a mortgage, if I don’t pay, the effects are the same. Owning a house doesn’t make you any more financially stable and reliable (I am living proof of this), it just makes other people see you in a better light. It’s a privilege, that’s all. And it’s, in a sense, a fake privilege too – if I borrowed £1m from the bank as a mortgage I’d be seen as incredibly affluent and notable, but the house isn’t ‘mine’ until I pay it all back – until then it’s technically the property of the bank or mortgage provider. Yet if I paid even 1% of that in total rent per year (which is a pretty realistic payment), there’s much less kudos and the feeling is I should be grateful for being allowed to live there.

Some areas are far cheaper than others. For the price of a beach hut in Dorset or Norfolk, you can buy a small street in Blyth or Ashington in Northumberland. [That may be an exaggeration, but not nearly as much of one as you might expect – at the time of writing, according to Zoopla the average house value in Ashington is £116,000, while in Guildford it’s a shade over £600.000]. But of course places are cheap (or expensive) for a reason, largely related to location (although in the case of places like Kirkby-in-Ashfield, where I lived, it’s also partly general ambience). And in any case no-one should be forced to move across the country just to find affordable housing – it should be available everywhere.

One of the phrases that’s often touted around in the housing market is ‘more affordable homes’. And often, the word ‘family’ is loud in its absence. Nottinghamshire, where I lived for most of this century, is dotted with ex-mining towns, where the collieries have been closed and built on, often by new-build housing. Much of this housing as deemed ‘affordable’, but it’s generally cheaply-built and quite pokey 3 or 4 bedroom houses. The feeling seems to be ‘put as many bedrooms as you can in the small space and that’ll do’. Because their target market is families who need more rooms, rather than creating better houses with fewer, but more spacious, rooms. A 3-bedroom house with small rooms is of no use to many people whatsoever; even a child-free married couple with a cat and a fetish for 1960s sci-fi (hello, Mother) only need two sizeable ‘bedrooms’.

In many countries, especially in Europe, houses and flats are advertised for sale with an overall area they take up (eg ‘house for sale, €538,000, 102m²’). The number of rooms the property has is mentioned in the blurb, often as an afterthought. Here in the UK, the most important aspect is the number of bedrooms. Houses are 2-bed, 3-bed, etc, as their primary selling point, and everything else is largely irrelevant – because they’re marketing directly to families, not to individuals. There’s also an interesting question this leads to as to ‘what defines as a bedroom’, especially in a property that only covers one storey, since surely anywhere you can put a bed in could count, thus ruling out only the kitchen and the bathroom. And in my life I’ve seen some very small rooms that have been counted as ‘bedrooms’ by the estate agent, in one case in a house I was looking at buying in Nottinghamshire even leading to an argument between the homeowner and the agent about the mysterious ‘third bedroom’. The homeowner insisted the wide space in the corridor on the way to the bathroom was simply a wide space, but the estate agent marketed it as a bedroom. Again, this shows the underhanded nature that agents seem to have in their pursuit of a sale, on their terms.

Prime Investment Opportunity

The other problem is that even in popular locations in large cities, with high demand for affordable property, there’s a large number of empty houses and flats, places that have been bought for investment maybe, or for second homes that aren’t lived in much of the year. This restricts the supply of available properties, making them less affordable to the majority of people. It was recently (May 2021) revealed that nearly 2,000 properties in Glasgow alone, valued at a total of over £300 million, had been vacant for over 2 years. The situation is obviously much worse in London; stats from 2017 suggest that 20,000 properties had been empty for over 6 months, valued at over £9 billion. Since these properties are neither on the market (neither rental nor retail), this reduces the housing stock thus pushing up prices for rent and sale for the property that is available, again pricing people out the housing market. This is especially seen in places like Cornwall where second-home ownership is pretty much destroying small towns and forcing a flight of, mainly younger, people into the cities, increasing the rental burden and continuing the cycle.

For many people, too, houses and flats aren’t even primarily seen as a place to live. Rather, they’re viewed as an ‘investment’. Just look at the property programmes on TV; they’re all geared up to buying cheap, to renovate, in order to maybe rent out in the short term, but certainly sell later at a profit. The primary focus is the money, not the building. Therefore it’s not in anyone’s interest to actually have people living in the place, as that might not only reduce the value, but indeed make the property unsaleable at a moment’s notice.

Summary

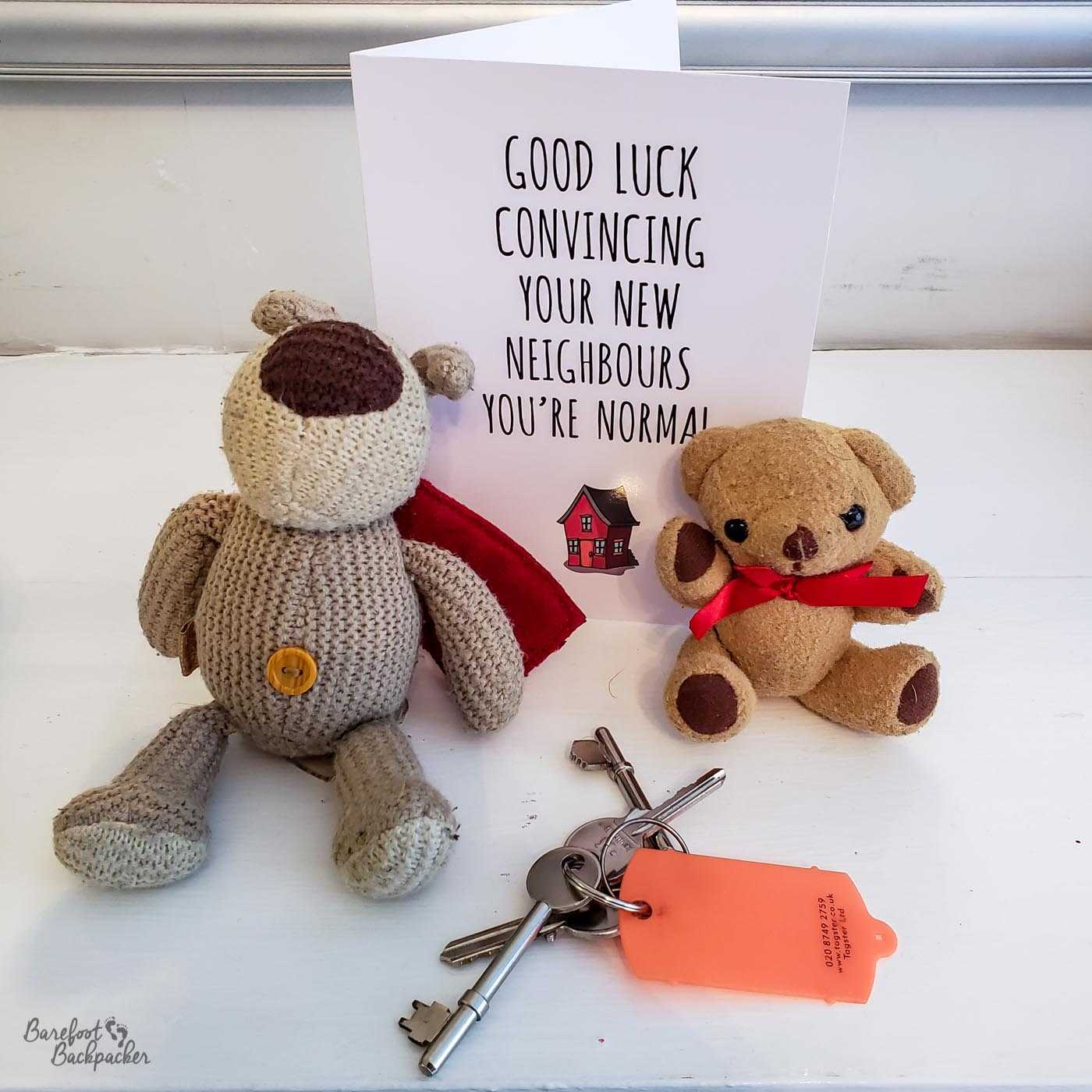

Baby Ian and Dave, with my new flat keys.

In the end, after all the hassle I had, we did cope with finding a flat in Glasgow. But there are many things that have irked me about the whole process. Firstly, the need to constantly chase, to poke the letting agents with a big stick, many people simply don’t have the time or the spoons for that. I couldn’t have done it without my VA, and most people simply aren’t in a position to call on a friend to engage in that level of commitment. Plus the whole ‘you have to visit in person’ thing, which was clearly not true in the first place.

But my entire experience of finding a flat in Glasgow opens the question of: what if you physically can’t visit a flat – either for reasons of geography, or, more pertinently, given the demographics of people who rent, for reasons of employment, finance, or disability? We seem to be making life incredibly hard for the very people most likely to be renting.

If you want to know more about where I moved to, I talk about it in Episode 42 of my podcast.