As you may know, one of my ‘aims’ is to visit every county, unitary authority blah blah in the UK. Not just visit for the sake of visiting, mind – that would be nothing more than a tick-box exercise – no, I have to be be able to say that I’ve taken something out of the area; a memory, an interesting take.

I was in London for a travel blogging conference (Traverse17), so it made it the perfect time to explore some of the less-visited outer boroughs of the Greater London area (there are 32 of them, 33 if you include the City Of London, and for my purposes they all count!); on this day I headed “South of the River”, much to the chagrin of the stereotypical taxi driver.

So, firstly, “Underground”.

Now, you might be thinking “but the London Underground, that’s easy”, but in this case no. In fact I was headed to deepest Bromley borough and the small middle-class suburb of Chislehurst. Very close to the railway station, down what appears to be a very residential, tree-lined cul-de-sac, is a small building that would go unnoticed bar the small signs indicating ‘Chislehurst Caves’. Even the inside is fairly-low key; the small museum about its history, with titbits about its geology and its use over time (mainly around its war effort) is somewhat dwarfed by the on-side café…

A quiet suburban cul-de-sac; a very unlikely place for a tourist attraction!

Even the entrance to the museum doesn’t give any inclination what’s inside …

The museum and café at Chislehurts Caves. Has the feel of a school trip.

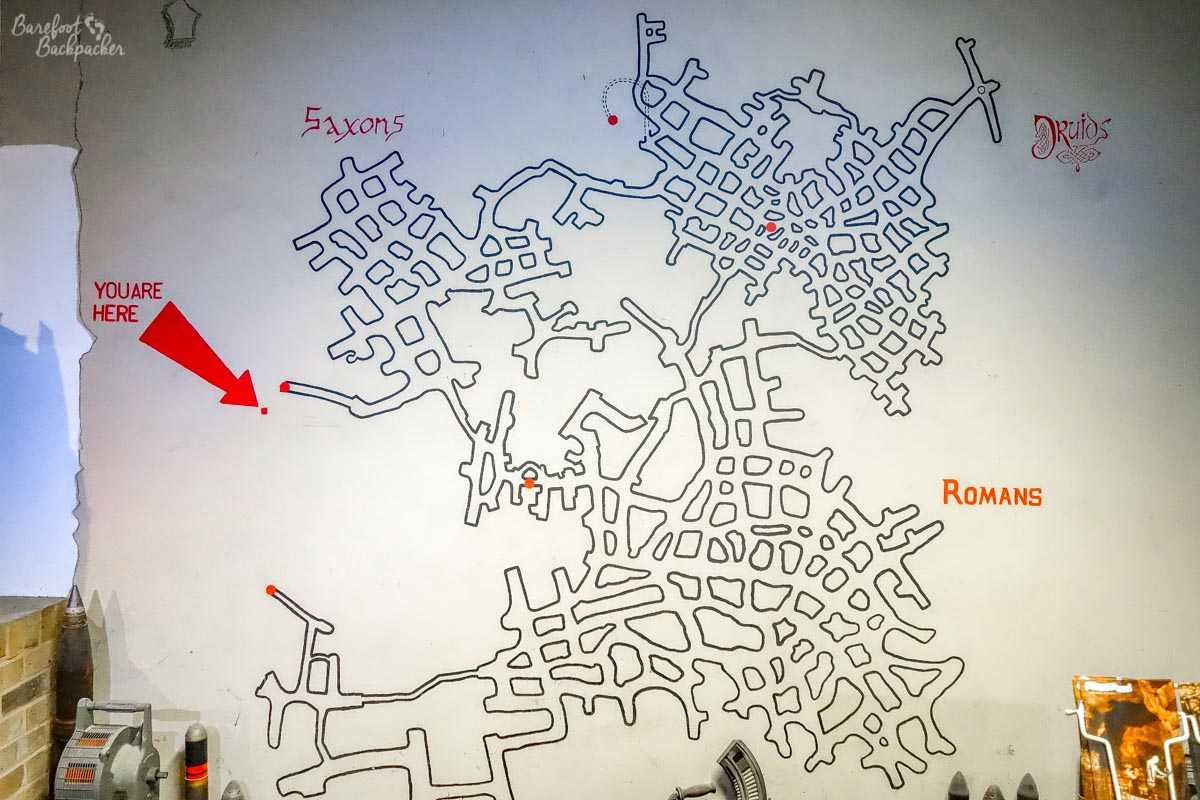

It would be more accurate to say ‘Chislehurst Mines’. This part of England has been noted since pre-Roman times for its flint, and up until the development of flint-less guns, the hills around Chislehurst had been mined for this resource; the passageways stretch out for several km in area. The caves themselves have been divided for convenience into three segments, reflecting the approximate period when they were dug. The earliest date from pre-Roman times, and some historians, as they are wont to do when they can’t work out exactly what they were used for, have assumed that they were the site of druidic ritual, including human sacrifice. The only suggestion of this is that a couple of the wider passageways in that part of the system end with a slightly raised alcove, and it’s believed that these were altars that sacrifices were led down to their fate. No evidence has ever been found of this, mind – no blood, no bones – so it’s probable this is just standard ‘religion-as-default’ belief. I swear if archaeologists of the future dig up our football stadia, without any other evidence they’ll come to the same conclusions. But then I suppose football is a religion to some.

A map of the caves, showing the different sections & how vast it is.

The caves were expanded during both the Roman and the Saxon periods, and were well used for over a millennia. Once the demand for flint had abated, however, the caves took on a number of other weird uses, from growing mushrooms to hosting rock concerts.

Mushrooms like a dark, dank, environment, and one enterprising chap had the idea of making use of these caves to grow a variety of experimental ‘shrooms as it was an almost perfect environment. No, not those kinds of ‘shrooms, though you never know what grows accidentally. Anyway, even though they stopped the industry in the 1930s, the caves are still technically owned by the company so they could well start again at some point.

As for the rock concerts; the acoustics are wonderful down there and during the 60s and 70s there was a growing passion for ‘intimate’ gigs (unadvertised concerts with a small but knowing audience);not just local bands either – the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin played here. The tradition continued into the 90s with the development of ‘rave’ culture – unfortunately although the caves themselves are (naturally) soundproofed, the road out is not, so the noise of ravers going home at 3am at the height of the ‘second summer of love’ was too much for ‘Middle England’ and the caves lost their license. Much to the chagrin of Led Zeppelin who wanted to do an anniversary concert down there in the 2000s but as a result couldn’t get insurance …

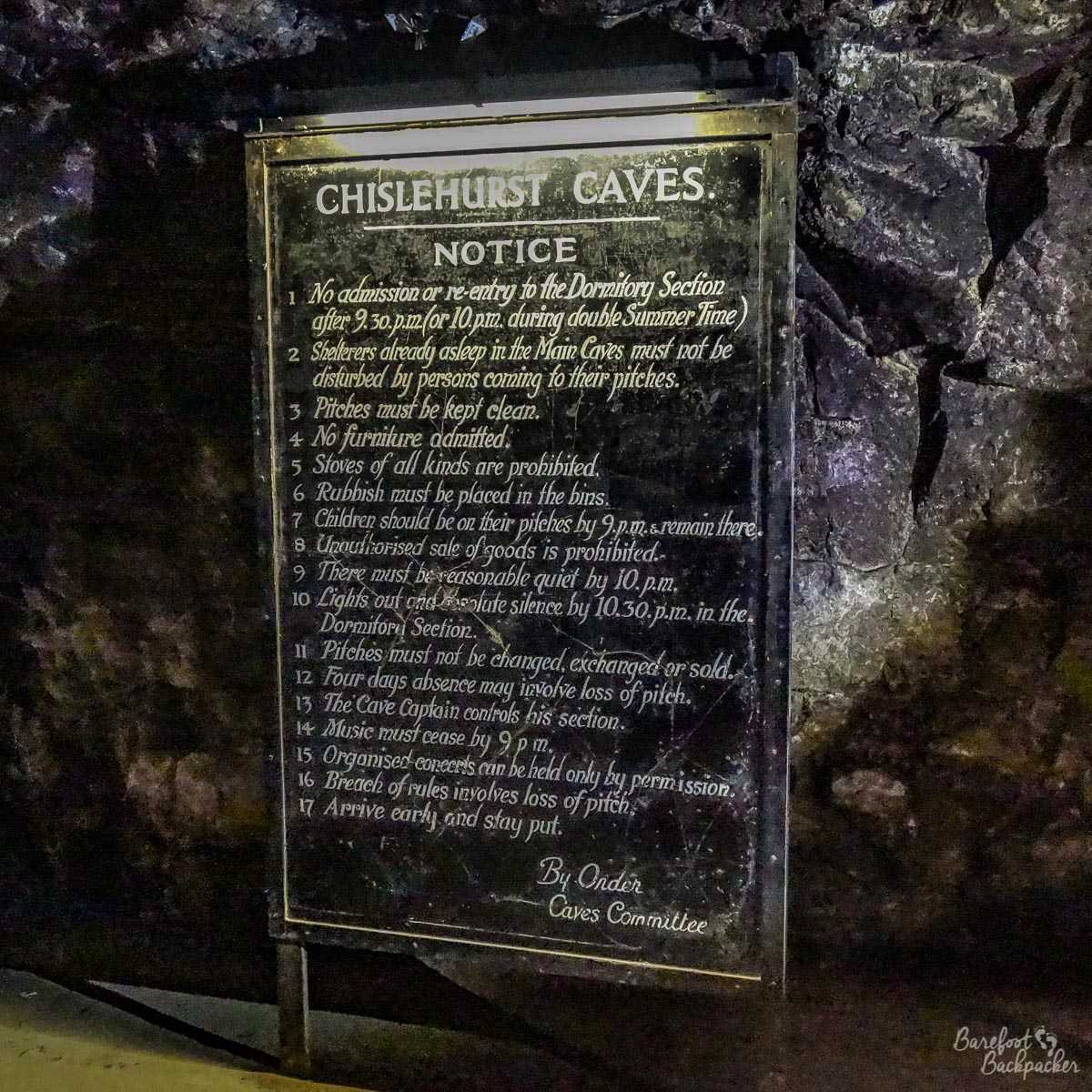

The main use of the caves however in recent times was during WW2. Now, the nearest city to my current hometown is Nottingham, and the caves under the city centre were used as an air-aid shelter. However, they were a mere bus-stop shelter compared to the ones here in Chislehurst. Due to its location and situation – an extensive arrangement of deep caves on the edge of London, close to the strategic targets in Kent, and capable of housing a large number of people – they became almost an unofficial town of scared citizens. At one point the population down here numbered upward of 15,000 people (more than half the current population of my home town!). In the caves were shops, a hospital, a barbers, a cinema … it pretty much functioned as a normal town, just underground and temporary. It was also quite an egalitarian setup – if you had lost your home during the bombing, you didn’t have to pay for anything, while those who were using it as a ‘shelter’ could pay for food, for lodging, etc, and the moneys raised were used to subsidise those who had lost everything. (Interestingly, after the war, all the unspent proceeds were given to the Dr Barnado’s charity, and while it’s not recorded how much was left over, it’s likely that it ran into the thousands of pounds).

The rules & regulations of the air-raid shelter; they were added to over time as more people came.

People using the caves as semi-permanent shelter were housed in what amounted to dorm accommodation; whole ranks of bunks, three beds high, were laid along some of the caves. The bed you were in was assigned when you first ‘checked-in’, and remained yours for the duration of the war; if you’d been amongst the first, or could prove a need, you may even have been assigned a small alcove you could put a curtain across, otherwise regardless of income or status, you got what you were given.

It was pretty safe down here, and the shelters attracted people from across the South-East – indeed people chose to become ‘permanently resident’ rather than making the trip back home every day; staying here for upwards of two months was reasonably common. In all that time though, there was only one registered birth; although many people fell pregnant, usually they were taken to one of the nearby above-ground hospitals in the daytime. This particular baby however decided to appear during one of the air raids …

You can only enter the caves on one of the hourly ‘tours’ but don’t worry; the guides (mine was Darren G) are very informative and chatty, and the tour itself lasts between 45-60 minutes, depending on how much you keep the guide talking!

Now, “Overground”.

Although London now has a designated ‘London Overground’ railway network, I’m referring to a different form of transport. It may surprise you to know that for many years, you could fly into what these days would probably have been called ‘London Croydon Airport’. Although given our penchant for naming things after distinguished artsy locals, it may well have been named ‘London Peggy Ashcroft Airport’, or, even, shudder, ‘London Ralph McTell International Airport’.

This was the site of London’s first airport. First used as an airbase during WW1, the site was expanded and developed to take advantage of the new world of air travel. Although flights generally at first only went to European destinations (making it an early version of London Stansted), it was the first civilian airport to serve London as a whole.

The old airport site is full of art-deco buildings. This (Merlin House) is now used for generic offices (cardboard boxes for several decades, now an air-con contractor), but at the time it served as the National Aircraft Factory.

The airport’s buildings are ‘of its time’. By which I mean a plethora of Art Deco and associated styles. The airport hotel still serves as a hotel, whilst the main terminal building still exists and is now an office block. The airfield itself is a recreation ground, and just to the south of the terminal building is a monument to the Battle of Britain, as Croydon Airport was one of the main bases for the Spitfires and Hurricanes that fought the Germans in 1940.

Croydon Airport was an important airbase during the Battle Of Britain in 1940, and was even quite heavily bombed itself one night. This memorial is dedicated to the few who did so much for so many, not just the pilots though but all those on the ground who contributed.

The old airport hotel – another art-deco building.

The last flight from Croydon was in 1959. It was closed because of its location – post-war development of London meant there was no more room for the airport to expand to be able to cope with more modern jet airliners. Traffic was rerouted to two airfields further out, that later became Heathrow and Gatwick. In fact, Gatwick Airport is only about 25km South of Croydon so it’s not much of a trek.

Another art-deco building; this is the old airport terminal building, now offices and a small museum (open rarely). The plane in front is a replica of the last commercial plane to fly from the airport in 1959.

Apart from the terminal building (now offices and a museum) and the hotel, the site of the airport is mainly occupied by a small commercial park and a large expanse of playing fields – though I didn’t venture too far into them it does appear that some of the old runway still exists as tarmacked segments in the park – one assumes they’re good for skateboarding and football. Interestingly, the local bus stop still refers to the ‘Croydon Airport’ history too.

The airport itself is mostly a playing field now; in the distance you can just make out what little remains of the tarmac runway and taxi route.

Between Chislehurst and Croydon, at least by public transport, is the large public park that once housed the Crystal Palace, originally built for the 1851 London Exhibition in Hyde Park and then moved to the delightfully-named suburb of Penge, seemingly at the whim of the local railway company to provide a reason for people to come here. Although the palace itself is long gone (victim of a fire in 1936 and then completely destroyed in the early days of WW2 lest it be used as a landmark for German bombers. Who obviously couldn’t read maps and didn’t know what the River Thames looked like), the site it stood in is now a large public park, complete with representations of mediaeval Italian architecture. And dinosaurs, apparently – one of the last links to its previous fame, but which, at the time of my visit, were being ‘renovated’. No, I don’t know how you can renovate a dinosaur either …

Unlike my last, misty, visit to a TV tower, this aerial is strikingly clear against the bright blue sky, standing proud above a verdant and chilled park.

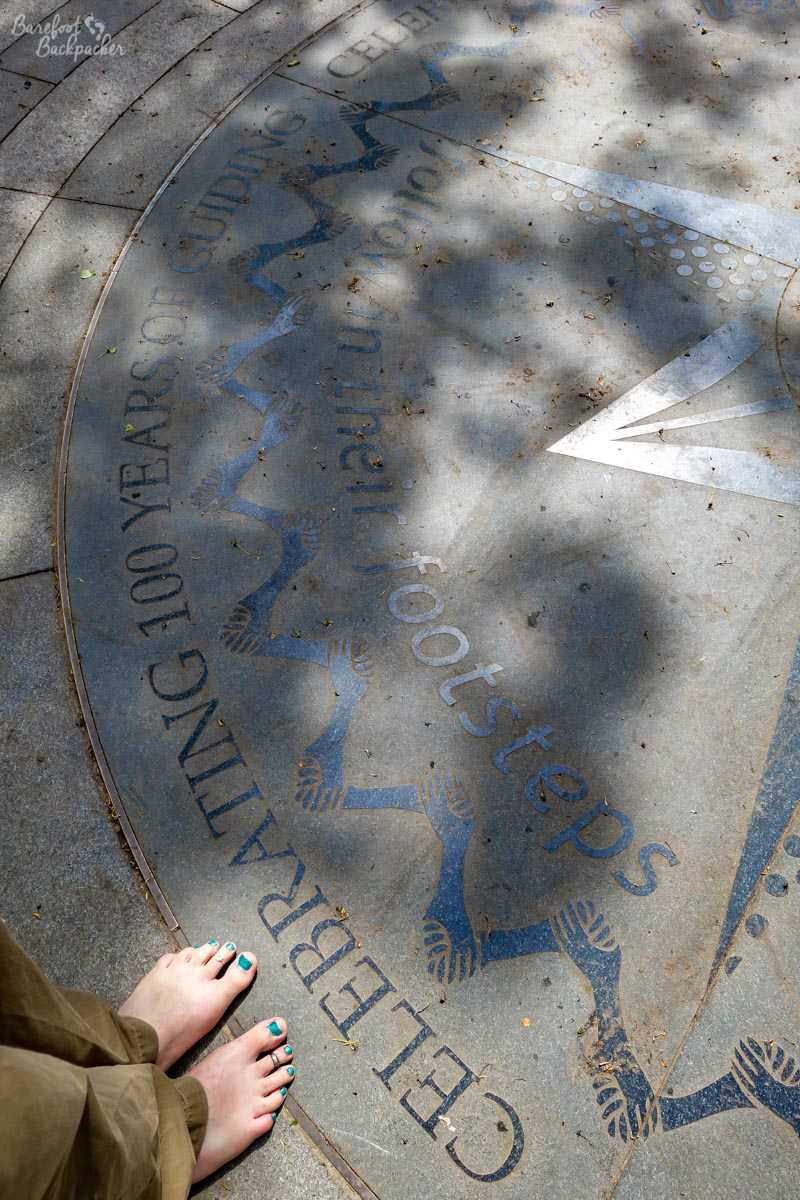

These days, the Crystal Palace park is notable for a TV transmitter (which serves this part of Southern England, being one of the highest points in South London), and a small bushy maze. This maze commemorates the foundation of the Girl Guide movement – in a sense it was here that the Girl Guides were created; at a Boy Scout meeting in the Crystal Palace park in 1909, Baden-Powell noticed how many girls had turned up, and as a result decided to create a, literal, sister organisation. The maze itself is more of a labyrinth, in that there are only a small number of dead ends, while in the centre there’s a mural and memorial to the concept of Guiding.

Inside the maze. Baby Ian & Dave are trying to cheat by leaping the fence.

Part of the memorial to celebrate 100 years of the Girl Guide movement. “Follow in the footsteps” it says…

In the past the Crystal Palace has been home to motor racing, the FA Cup Final, and many concerts and exhibitions. The only link to this past now is that the site of the old football stadium (which also lent its name to the current Crystal Palace football club, who played there in their early days) is now the “National Sports Centre”, home to training pitches, a competition-standard swimming pool, a non-league football club, and, somewhat obscurely, two American Football teams.

The National Sports Centre – site of the original stadium. Which probably looked more impressive.

Walking around the park is quite pleasant; for somewhere so close to the centre of London it’s a welcoming green space. But not quite as vast and strangely remote as my next port of call…

“Wombling Free”.

Wimbledon is famous the world over, mainly for sporting endeavour. The 1988 football FA Cup being won by the local ‘Crazy Gang’ who, after a controversial and distinctly un-British move to the soulless Milton Keynes founded a new club (AFC Wimbledon), one of the very few fan-owned clubs in the UK Football League system and often now ironically in the same league as the bastardised franchise club that the original club became. They recently moved back to Merton, taking over the site of what was one of the last remaining greyhound stadiums in London. Plus of course Wimbledon’s the home of British Tennis – the All-England Wimbledon Club being the home of one of the Majors on the Tennis Circuit and a representation of the sport in itself. But sport does not concern me today. Rather, Wimbledon is the location of Wimbledon Common; home, to the whole of what may be categorised as “Generation X”, to the first eco-warriors, the Wombles.

This was the first trail I found in the Common. Even after a few minutes’ walk, I realised this was much bigger, much more ‘open’, and more countryside-like, than I’d expected.

As a tourist and a ‘foreigner’, the biggest take-out from Wimbledon Common is just how big it is. It’s seriously impressive just how much land is still wild and open so close from the centre of London – in my head it was going to be a small park, but in reality it’s a huge expanse of scrubland, forest, and open countryside. I came in from Wimbledon Village, a quite pretty, preserved, part of London with old buildings and a certain style, and an hour and a half later (having seen virtually no-one aside from the occasional jogger and a few golfers – on the West side there’s a golf course, unfortunately, but it doesn’t take away from the remote beauty of the centre), I was in a council estate in Kingston borough (somewhat unexpectedly, on several counts!).

The Common itself is a protected ‘Biological Site of Special Scientific Interest’ (meaning it can’t be developed because the flora and fauna in the area are worth preserving), and covers an area of 460 hectares. I’m not very spatially aware, so I had to look up that this is similar in size to just under 460 rugby pitches, or 1½ times the size occupied by the ‘City of London’.

It feels much more like a country park than a mere piece of common-land. It’s certainly vast enough for Baby Ian & Dave to play hide-and-seek in.

At its heart is Wimbledon Windmill. Built in 1816, it’s a pretty well-preserved example of its type, although long since out-of-use – it ceased operation in 1864 because the local landowner wanted to use the space for residential and commercial development, but there was such local opposition to it that the local council acquiesced and designated it as ‘common land’, preserving it in perpetuity – as in indirect result the windmill itself became a house. It’s now a museum, detailing windmills in general as well as this one in particular, and has detailed models of how the mill would have worked in its heyday. Unfortunately it’s only open on weekends and bank holidays; my visit was on a Thursday …

The windmill, as seen from near the entrance (which appears to be around the back, judging by where the sails are).

Incidentally, the Windmill itself has a link to my previous stop; it was here that, in the early 1900s, Lord Baden-Powell wrote parts of his seminal work ‘Scouting For Boys’ (that launched the Boy Scout movement).

In front of the windmill is this axle. It’s an old part of the windmill itself, and gives you a feel of just how big/powerful it is.

Elsewhere in the Common are the foundations of iron-age hillforts and the sites of possible Roman camps, although very little remains now save vague ramparts in the ground. Much of the Common is made up of a series of footpaths and horse-riding trails passing through scrubland and forest; apart from the occasional cottage in the middle of the trees, it does feel like you’re in the middle of the countryside rather than in the suburbs of one of the largest cities in the world; it’s definitely a good place for relaxation and exercise.

I did not see any Wombles, unfortunately. Maybe they were camouflaged. Can you see two other ‘creatures’ that are in the woods though?!

Unfortunately I didn’t see a Womble. I guess they were scared off by my noisy presence!

Authorities visited: Bromley, Croydon, and Merton (27 April 2017).

Super interesting post. And not too long at all! 😉 I was a Brownie & Girl Guide when I was younger and I did Camp America at a Girl Scout camp – I can’t believe I didn’t know about the maze in Crystal Palace.

Thank you 🙂 I have to say I wasn’t aware of it either until I walked past it … ! It’s got representations of around 10 different animals on posts throughout the maze too (representing the ‘pioneering spirit’ of the girls in the movement, apparently!) – it’s a separate task to find them all. The maze existed before Guiding, but Baden Powell refurbished and promoted it, and it’s now seen as a memorial to the movement. I was never a scout or anything so it’s all completely an alien concept to me lol! 🙂

Even bigger and just as lovely is nearby Richmond Park. Also, while on Wimbledon Common you should visit the little-known Cannizaro Park

Cheers! There’s always something new to discover 🙂