My trip to Vanuatu accidentally coincided with Independence Day; this was unplanned (indeed, I didn’t even know when Vanuatu’s Independence Day was until I got there!) and, I have to say, had the potential to be slightly awkward. As already noted, Vanuatu has a habit of ‘closing’ at the weekends, and Independence Day itself fell this year on a Monday, so obviously the idea of a long weekend without the ability to organise anything didn’t initially thrill me. That said, I spent the weekend in Vanuatu’s ‘second city’ (population about 16,000) of Luganville so at least I was somewhere exciting.

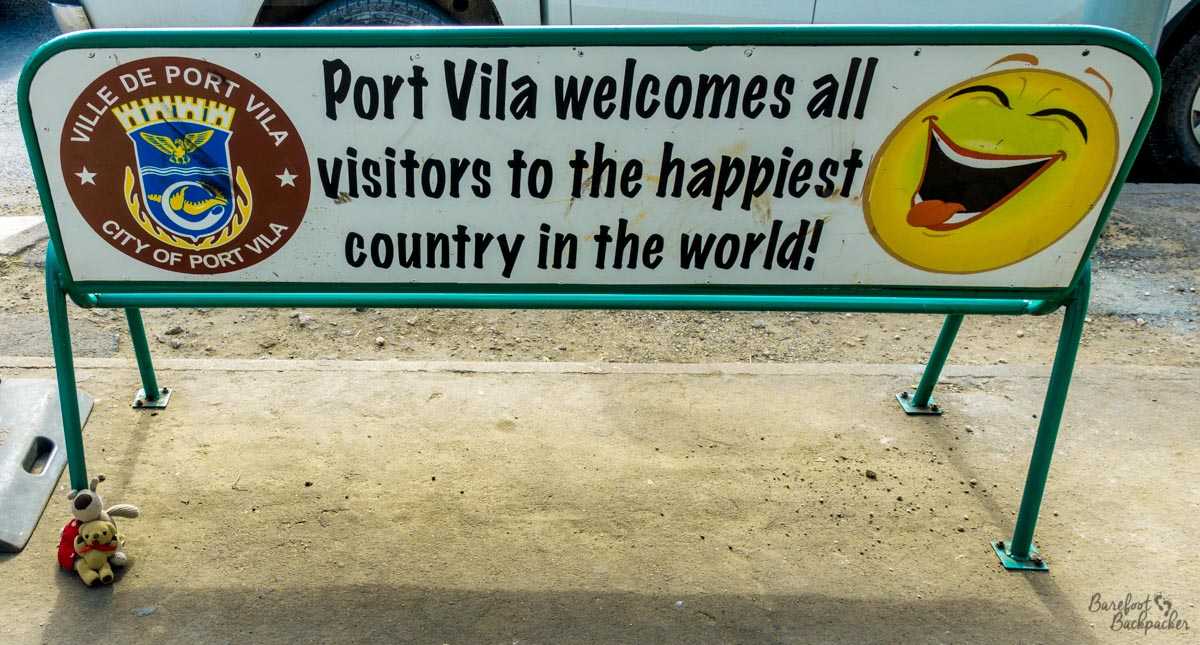

Vanuatu is proud of itself, and is often voted “World’s Happiest Country”.

On my visit, Vanuatu turned 38 years old – a country on that border between Millennial and Generation X. There’s still a lot of people around who remember well what life was like before independence, and as an aside I did encounter some people who had mixed feelings about the concept of independence, but life in the islands before then was … shall we say, a little complex.

See, as the colony of the New Hebrides (named because early explorers felt the islands resembled the Hebridean islands off the coast of Scotland, except that Scotland doesn’t have active volcanoes and no-one’s going to eat you. Unless they deep-fry you first, I guess), the islands were run by the British.

And the French.

At the same time.

This almost unique situation (other colonies tended to be split on colonial lines, like Togoland, or became united only after independence, like Cameroon) seems to have developed due to British apathy mixed with a tinge of bloodymindedness – in the mid-1800s many of the islands had been colonised by the British but the British government didn’t appear to be interested in taking direct control, despite pleas from the colonists themselves. It was only when French missionaries and colonists from the South and East (New Caledonia is the next island chain south of Vanuatu, and French Polynesia isn’t that far away, relatively) started to arrive and outnumber the anglophones that forced the British government’s hand, by which time it was, of course, too late.

The result was The Condominium, a policy of dual-control by both colonial powers. This worked … about as well as you might expect. Imagine if Belgium wasn’t two separate regions, but rather all jumbled up in a series of enclaves and exclaves, a la Baarle-Hertog. The two powers had different religions, school systems, police forces, even laws, famously including the rules of the road … the French drive on the right whilst the British drive on the left, and the colonisers saw no reason why this shouldn’t also be the case in the New Hebrides. Fortunately the roads in the country aren’t really designed for fast driving, so I guess it was never as much a problem as it sounds. This though was just one of the more outlandish examples of how the two powers never really worked together for the benefit of the country – a bit like divorced parents both passive-aggressively fighting over a child.

A typical road in Vanuatu. Worry less about traffic coming the wrong way and more about your suspension, I suspect.

One of the effects of this in independent Vanuatu is that the country has notable, if somewhat random, influences from both nations. Firstly, the language. As already noted, Vanuatu has the densest variety of languages in the world, so in order to facilitate trade, they needed to find a common tongue. Parts of the country favour French, while most prefer English, but even this seemingly has no pattern – it’s not that some islands speak one or the other, rather it’s down to village level; one village in Northern Malekula speaks French, those around all favour English. But neither is the national language; while not necessary fluent, this means many Ni-Vanuatu speak four languages; the two colonial languages, their local tribal language, and the national language Bislama.

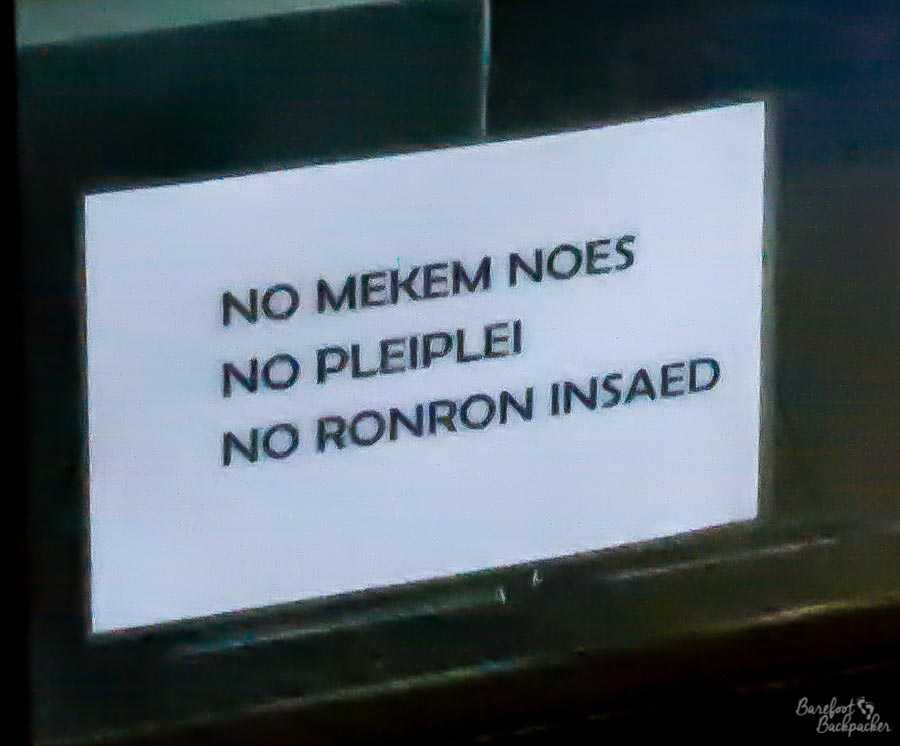

Sign in the Vanuatu museum in Port-Vila. Don’t make noise, don’t play, don’t run inside (the building).

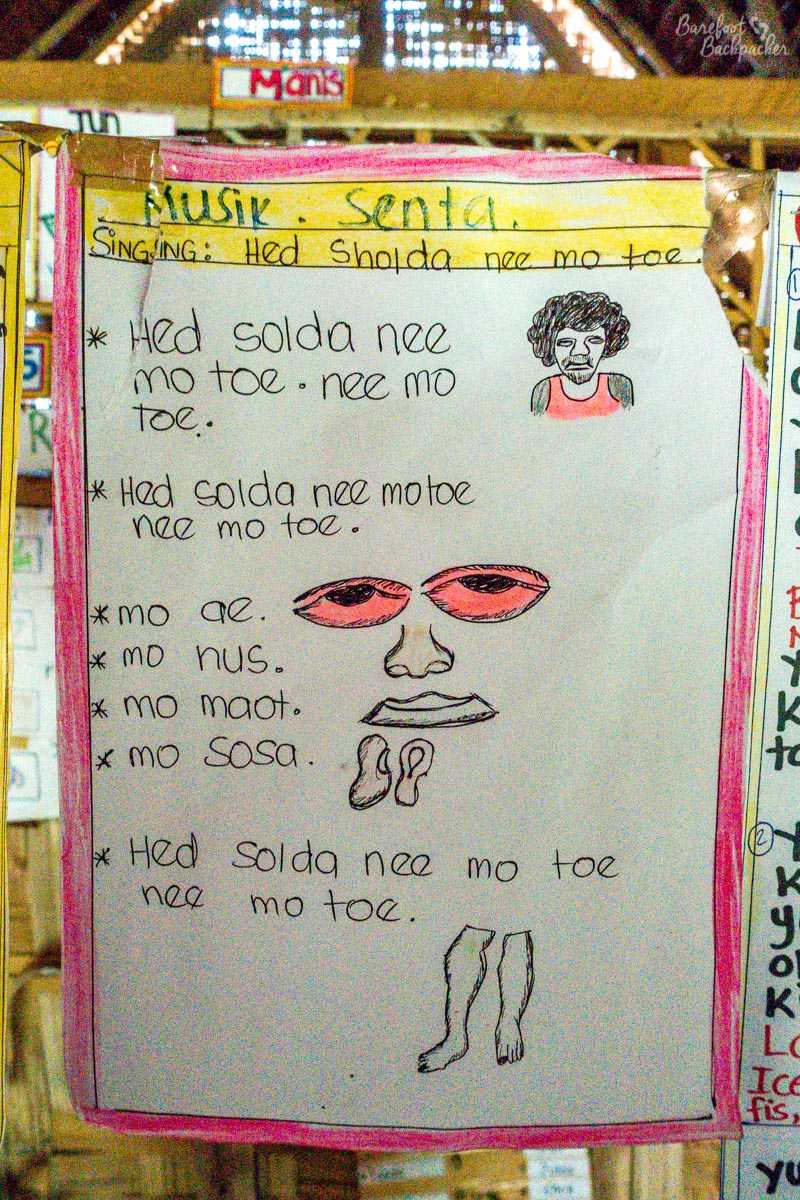

Bislama is similar to languages spoken further North, like Tok Piksin in Papua New Guinea, and indeed there’s a degree of mutual intelligibility between them. It developed as a creole, a trading language and lingua franca as a means for islanders to be able to communicate with each other, and it’s estimated to be 95% based on English, with a few French and local words thrown in (‘bonne nuit’ and ‘allez’ being two of the most frequently heard). Spoken Bislama is too quick for a non-speaker to pick up, although your ear is drawn by the frequence of English-sounding words; it feels like you should be able to understand it if only you concentrated. Written Bislama however … to my eyes it reads a bit like a parent talking to a child, or, more concerningly, the sort of speech ‘white man’ make to ‘native American’ in 1950s cowboy movies. Vanuatu blong yumi. Bigman yu go pleiplei, Yu save? (‘save’ here is pronounced ‘savvy’). It’s often dismissed by people (both Westerners and locals, interestingly) as ‘oh, it’s just English with a few random ‘longs’ and ‘blongs’ thrown in’, but it is obviously much more structured than that; ‘blong’ in particular is the possessive so ‘my leg’ becomes ‘leg blong mi’ (literally: ‘the leg belongs to me’).

A famous children’s song in a school on Malekula. See if you can work out what song it is. It may help to sing it rather than read it.

French influence, apart from the fact Vanuatu sorted out its road chaos and chose to drive entirely on the right, is less easy to pin down, but there’s certainly a French ‘vibe’ and ‘feeling’ to society. I arrived in the country the week after France won the men’s football World Cup, and there was still a strong feeling of euphoria about it – the whole country seemed to be behind the French. They had been kind of hoping for a France-England final, and no-one seemed willing to admit who they’d have supported in such a situation, but certainly I got the impression that cries for ‘les bleus’ would have been stronger than those for the ‘three lions’. French influence is helped by the closeness of New Caledonia, and the vast majority of tourists/backpackers I met during my time in Vanuatu were French. While both Australia and New Zealand are also close, and served by regular flights, the impression I got was that these were countries used more for commerce than culture – locals chose to go there for work, whilst many large businesses in Vanuatu were owned/operated by Australians who tended to stay in their own resort-oriented ghettos.

Minibus in Port-Vila, emblazoned with the French Flag.

As an aside, many Ni-Vanuatu appear to welcome the domination of business by ‘white man’, because they have relatively little faith in their own countrymen to work efficiently. All the locals know about ‘island time’ and the vagueness of deadlines, and feel that while it’s a great way to ‘live’, it’s not a useful way to ‘work’.

The main stage for the Independence Day celebrations, at Unity Park, Luganville.

My first experience of the celebrations for Independence Day came on the Saturday I arrived in Luganville. I was a little wary about the weekend in general, since I knew not much would be open and the introvert in me would be severely battered – I knew I wouldn’t have much scope to get away from it all. My motel was close to Unity Park – a small grassy park between the main street and the sea which would be the centre of the festivities for the next three days – but fortunately just far enough away from it for the music to not be too much of a problem. The coastal side of the park was lined with food stalls (kebabs, chicken/rice dishes, sausages-on-a-stick, nothing too outlandish) and the occasional game (of the ‘throw a dart at the board, points mean prizes’ type), while in the centre of the park was a large stage decorated with colourful banners, almost empty save for huge speakers, an emcee hidden by a huge desk, and a couple of musicians. The main road was closed off and cars diverted; in the way were two small metal football goalposts, and lots of people, mainly children, milling around on the pavements seemingly waiting for something to happen.

People playing Futsal on the road alongside Unity Park.

What was happening was futsal.

It’s not a sport I’m overly familiar with; perhaps surprisingly for a football-mad nation, it’s not a variant we play or advertise much in the UK. It seems to play a bit like an outdoor version of 5-a-side, without the pedantic rules about the ball needing to be under head-height. Play seemed to be about 10 minutes each way, 5 people on a team, unlimited substitutions. It turns out Independence Weekend was being used as the timing for a major national futsal competition; I don’t know how many teams were taking part but over the following days I noticed a whole host of posters advertising for teams.

The boxing ring in Unity Park.

The other sporting event on the Saturday at least was boxing. In the park was a small boxing ring and once the futsal had finished for the day (about 4.30pm) everyone wandered over to the boxing ring for what again seemed like a national competition; an endless series of fights stretching well into the dark evening, with up to three rounds per bout covering the range of boxing weights, although I didn’t notice any bigger fighters. Some of the fighters were presumably local crowd-favourites as the atmosphere when they fought was very excited.

The boxing tournament lasted deep into the evening.

Much of Sunday afternoon was spent sat in the park listening to music coming from the stage. Some of it was pre-recorded, some was live. Music is a big part of Vanuatan life; it’s not uncommon to be sat in a bungalow on a remote island and yet still hear someone walking down the road carrying some kind of ‘ghetto blaster’ (not a phone!) playing music really loudly. Inconvenient if it’s 9pm and you’ve already gone to bed.

Unity Park. Main stage in the centre, with a musician playing. Food stalls in the background.

Incidentally, the most popular music in Vanuatu seems to be reggae, or at least that kind of vibe. There is a certain Caribbean feel to the scenery (especially on the coasts), with beaches, palm trees, and sunshine, and the striking colours of green and yellow are common (they’re even on the flag), but it’s obviously a completely different ethnic culture. I don’t know if that’s an affinity with other colonised ‘black’ islands (even the island group – Melanesia – means ‘islands of the black people’), or some kind of ‘convergent evolution’ that makes all tropical islands develop the same beat, in the same way that most ancient civilisations defaulted to the pyramid as being the pinnacle (sorry) of architecture, but given the number of Bob Marley posters I saw in places like barber shops, I suspect strongly the former.

The formal ceremonies however were on the Monday morning, Independence Day itself. Another thing the British seemed to have left was a preference for over-elaborate small military displays; Unity Park was filled with people watching s small troop of the armed forces and a similar sized body of police parade around the park then stand to attention during speeches given by someone important – the governor of Sanma Province or the Deputy Prime Minister or someone of that ilk (his introduction was given in Bislama over a dodgy public address system). All I know is that he spoke for an inordinately long time and he wasn’t the greatest public speaker in the world – even the locals were in equal measure embarrassed by his manner and bored by the length.

The police and armed forces standing in formation.

Although mostly in Bislama, the gist of the speeches were easy to grasp, and they matched the feelings I’d got from looking around Luganville in the previous couple of days. Rather than talking about the fight for Independence and the legacies of colonialism, Vanuatu’s Independence Day celebrations were almost exclusively about Vanuatu as it is now; about what its achieved in the past 38 years, about its current successes (the city of Luganville becoming a major economic centre of the region, with direct International flights from Australia), about its current problems (mainly geographic; recovery from recent cyclones, but mostly the ongoing volcanic eruption that’s devastated the small island of Ambae and caused its effective complete evacuation), and about how the country is strong in unity and together it can strive to be the best. It wasn’t a ‘we beat the foreigners’ celebration, it was a ‘we are Vanuatu’ celebration; inclusive patriotism rather than the slightly bitchy nationalism as seen in countries like the UK of late.

Part of the parade by the armed forces.

The highlight of the morning was the flag-raising ceremony; a small squad marched very slowly and in perfect step to the stage, picked up the flag, and carried it in exaggerated ornate military step to the flagpole. To the sound of what I assume was the Vanuatan national anthem (it’s not something I get to hear very often, in fairness), the flag was raised and nobody stood up especially for it.

The raising of the Vanuatan flag on Independence Day.

The dignitary left in a convoy of limos, and the military paraded away from the stage before passing out in the crowd (militarily passing-out not physically passing out – though it was really hot the leader of the police squad made sure his company had enough bottled water whilst standing listening to the endless speech to see them through). They then spent a little while talking to, and having pictures taken with, the public before heading off to do their own thing.

A small company of soliders posing for pics after the ceremony.

That wasn’t quite the end of the festivities; the evening entertainment in the park consisted of singers, local dance troupes, and endless announcements of the results of all the sporting and other activities/competitions that had taken place over the whole weekend. There were also some speakers talking about the history of the islands, and of course a couple of nods towards religion.

There were no fireworks; while that sounds like an odd thing to say, it just feels that every such celebration in the Western World is punctuated by loud explosions and lights in the sky (July 14th and 4th are both very odd days to do this in the Northern Hemisphere, I always thought, but still). Rather what there was was excited yelling amongst the people, music, and the occasional car horn. Oh, and a couple of rounds of gunfire in the air during the Monday morning parades that definitely woke the crowd up.

“Welcome to Vanuatu” signage, in Port-Vila.

Have you ever experienced an Independence Day in a foreign country?

For other cultural experiences on Vanuatu:

* The culture and history of Malekula Island, including details on cannibalism and the ‘Nambas’ tribes

* Sampling some of the local ‘brew’, Kava, on Ambrym island. It didn’t end well …

For a more general overview, I recorded an entire podcast on Vanuatu. Give it a listen!

—–

Like this post? Pin it!!

The Independence Day celebrations I attended took place 28-30 July 2018.