Malekula, the second largest island in Vanuatu, is noted in culture for two things, and they’re kind of related, though not in a way you might find on Fetlife or RedTube. When I say penis sheaths and eating people, I’m meaning things literally, not figuratively.

There are 30 languages spoken on Malekula, an island the size of West Yorkshire (at just over 2,000 sq km, it’s also about half the size of the US State of Rhode Island) with a population of around 23,000, but while this sounds quite unlikely, the interior of Malekula is basically thick jungle, big hills, and many rivers; without considerable exploration, it’s quite an unknown wonderland. This meant that local villagers would rarely be able to explore the world further than a km or so from their homes. The other problem was that many of these villages were somewhat ‘insular’ and tended to get along badly with neighbouring villages (matters usually reached a ‘war’ whereby three or four people from one side would get killed), so in general, communication and trade were limited.

Two general tribal systems grew, though. These were the Big Nambas and the Smol (Small) Nambas. They were distinguished by their ‘Nambas’; a ‘Namba’ is the name given to the ornamental and spiritual ‘sheath’ worn over the penis by the male members (stop it!) of the tribe, and in fact pretty much all they traditionally wore. Those in Big Nambas tribes wore big ones, whilst those in Smol Nambas areas … you get the idea. There’s a line across Northern Malekula – to the North and East of this line, tribes were generally ‘Smol Nambas’, whilst South and West they were ‘Big Nambas’.

It’s fair to say that the two cultures generally hated each other, even though in essence the two were very similar, being distinguished mostly by their sheaths. They both, for instance, believed in the value of the pig; indeed this belief was shared across many of the islands now known as Vanuatu – a pig’s tusk is even on the national flag. Whenever there was some big event in a village, say a new chief being coronated, or an important marriage, or a celebration of a recent victory, there was a big celebration and a feast. The worth of the village, or of the person marrying, or of the new chief’s standing in the tribe, was measured in the number of pigs that they could source for the celebration; indeed it wasn’t unknown for some villages to suffer what would now be called an economic depression and near bankruptcy because they put so much resource into buying (and killing) pigs rather than everyday affairs. Pig tusks were used as jewellery and status symbols, but they had to be naturally grown in a certain way, which generally wasn’t much good for the pig. The upper canine teeth were removed so that the tusks had room to grow naturally – they tended to curl inwards, back inside the jaw, to create a kind of ‘loop’ effect. Really prestigious chiefs wore tusks that had been allowed to curl twice through the jawline. Needless to say waiting for this to happen was an

arduous task, not least because having fewer and warped tusks like this meant the pigs had to be fed by hand.

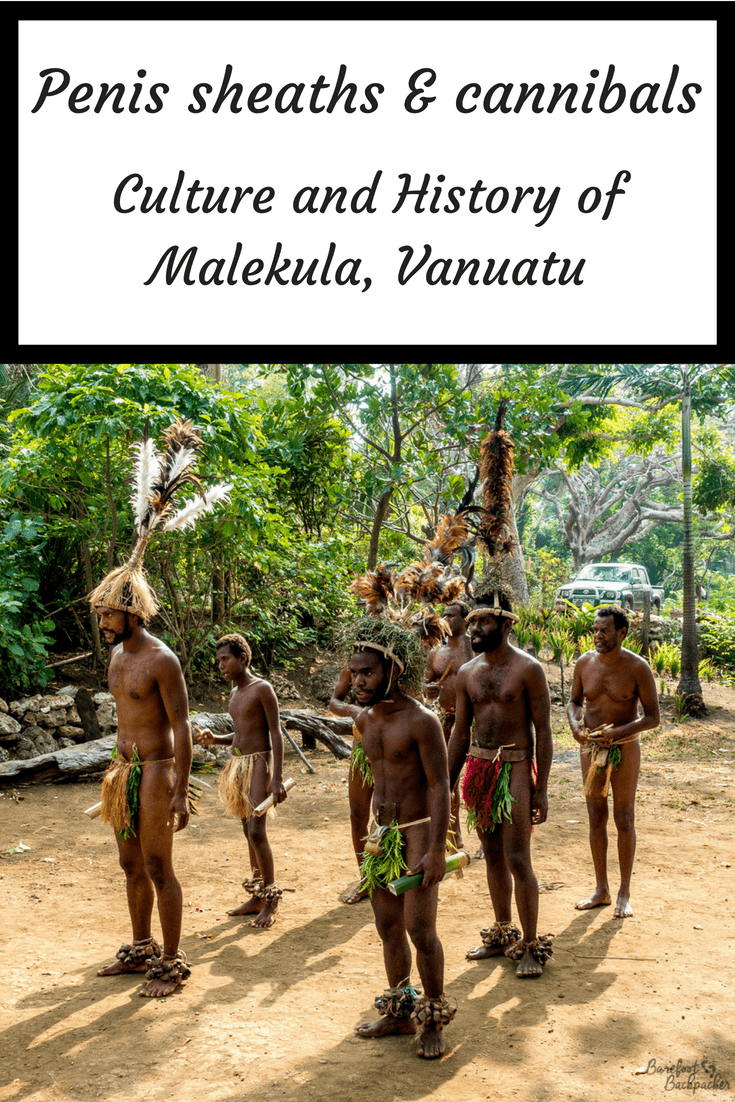

Of the two tribes, I only managed to get to visit a Smol Nambas village (it was apparently proving hard to contact the Big Nambas – oh do stop it Aggers!), but I had a couple of hours with them to see their traditional dances, clothing, food, pastimes, etc. For the most part they no longer wear just the nambas outside of tourist season, but they do work on keeping the traditions alive, and everything else is a part of everyday life.

One of the dances performed by the women and children of the tribe.

They have special and separate dances to celebrate and commemorate almost every event, and most of them diverge on gender lines – ‘mixed’ dances are very unusual. Traditional garb for these dances are grass/palm skirts for the ladies, and the aforementioned penis sheath for the men, tied on with a garland belt. They’ll also often have thick palm anklets with bells on, that jingle when they stamp their feet.

One of the dances performed by the men of the tribe.

One of the more common dances is to celebrate the handover of power to a new village chief. Now, I may have got this wrong, but it seems the concept here is that one of the most important roles of the chief is to have a son. The events of the son’s childhood and adolescence are celebrated by the village, but when he turns 18, he’s expected to get married. Once he does so, he becomes the new chief, and his father hands over the power and chiefdom of the village to him. In return, the father becomes a kind of ‘wizened old sage’ who offers advice as and when necessary, and the son will tend to defer to his seniority and experience. It is often the case that the son’s grandfather (and even their father) is also still alive, so the new chief may have a series of older men to seek advice from, all of whom have been chief before him.

If a chief dies without a son, then the chieftainship will pass to the son of his brother. If there is no-one available in the village they will look to a neighbouring village for someone ‘princely’ to take over.

The traditional way of making fire – involving bits of wood and lots of breath.

The men’s role is to fight, hunt, and run the village. It’s the women’s role to craft, build, and cook, using locally-sourced material, obviously. Palm-type leaves (from the coconut or pandanus plants) are chiefly used in a tight-weave for mats and house decorations; for a skilled weaver this is a matter of minutes rather than days so it’s a pretty efficient process. They also make simple, compact, but intricate children’s toys; rattles, pinwheels, fun bracelets etc out of the leaves.

Making laplap; this is before being cooked. The pounded yam is spread inside a banana leaf, which will be then inserted into the bamboo stem below her before being cooked on the open fire.

Making coconut milk by carving out the coconut flesh, pounding, and mixing with water.

Making laplap; this is after being cooked. It’s that shape having just been pulled out of the bamboo stem.

The typical food is laplap, usually made from yam (the yam is perhaps the most ubiquitous item of food on Vanuatu). It’s made by firstly peeling the yam, then grating it until it turns into a mushy substance. This is then mixed with a little water or coconut milk, and fed into bamboo tubes which are then laid on an open fire. When the bamboo turns brown (this takes around 10 minutes) the laplap is cooked. The bamboo tube is cut open, revealing, in this particular case, a substance with the colour and texture of raw sausagemeat; soft and reddish. This is either cut into small pieces and dipped in coconut milk as a snack, or rendered whole around a puddle of coconut milk filled with prawns or chicken, and bits pulled off and eaten like bread.

Laplap Yam, as cooked and served on banana leaves. You eat it with your fingers, after dipping the chunks in the coconut milk.

The other thing they traditionally tended to eat though was … each other. Malekula was one of the islands famed in the South Pacific for its history of cannibalism. Usually this would occur after a battle between tribes, or if a member of one tribe came too close to areas controlled by another. We’re not talking mass banquets of human flesh here; generally only a couple of men would be captured, taken to a site specifically designated for the purpose, then killed and eaten. One of the guides on my treks implied that not all of the body was eaten, only parts of the upper torso near the armpits, and the ribs, but I’ve found no evidence either way if this is true. It would be kind of odd if it were though – surely the leg would be the best bit?

The stone on which the tribes would execute prisoners – they’d stand with their head on the top, and then have their heads cut off with the machete.

Deep in the jungle just off the Big Nambas Trek, now long overgrown, is one such cannibal site, with some associated remains, but enough to get the feeling of what was going on. Firstly, the captured men were led to an upright stone, where they’d be positioned and killed, probably with a machete or some such. The body would then be taken to a specific area separate from everything else, where the corpse would be butchered like any other dead animal, before being cooked and eaten at the nakmal – the Ni-Vanuatan equivalent of the working mens’ club (no women allowed in any part of this process; indeed the female tour guide with us on the trek didn’t set foot anywhere past the initial killing stones) – probably being washed down with a few shells of kava (more about that in a future post).

The cannibal equivalent of the butchery, where the body of the prisoner would be chopped up and cleaned etc.

At this particular site, undisturbed on the ground, is the place they discarded the bones; it may have been the fire itself in fact. Clearly present are shin bones, half a skull, a few pots, and a large pig’s tusk, suggesting someone eaten here had been somewhat powerful, or at least notable.

The fire, and where bones and inedible parts would be discarded. Here we can see some shin bones, a skull, and a pig tusk jewellery item, suggesting whoever these bones were from was an important member of another tribe.

There is a stereotype that South Pacific cannibals ate foreigners – missionaries in particular but also explorers. While this is very true (and in an early example of colonially racist behaviour, when the first Western missionary was killed and eaten, the church leaders decided to send more expendable missionaries from Samoa rather than Westerners, under the pretext of ‘well they might listen to someone more like them’), the majority of cannibalism was inter-tribal rather than inter-national.

A missionary was allegedly responsible for stopping cannibalism on this particular site, however. The story goes that one came to the chief of the tribe, and commanded him to turn to the ways of “The Lord”; this meant of course abandoning tribal ceremonies, not having multiple wives, and not eating humans. To prove his moral authority, he told the chief to build a big hole in the ground, and that if the Lord’s Word was true, the hole would fill with water by the end of the day. Presumably to humour him, the chief got his tribe to build a hole. That afternoon, the rains came so heavily that the hole got filled up. The chief, suitably impressed with the missionary’s ability to predict the weather, converted instantly. How true that story is, eh, I’m unconvinced, but the hole itself does exist. I mean it’s all completely filled with jungle now so it just feels like a natural hill, but I did stand in it!

Across the island though, cannibalism was still being practised within living memory; indeed the guide that took me to Losinwei waterfall claimed to be 80 years old and that his father had been a cannibal. My guide, however, had never eaten human thus could not confirm the long-held belief that we taste like pig. To be fair, he’d probably never eaten pig either, given they’re probably more valuable than humans on Malekula anyway.

If you’re interested in knowing more about Malekula, I’ve written a couple of other posts on it:

* A general overview of the island, covering transport, food, accommodation, daily life etc, and

* Trekking on Malekula, specifically a couple of treks on and across the ‘Dog’s Head’ in the north of the island.

If you’re interested to compare with the culture on another Vanuatan island, I wrote a piece about the northern island of Gaua, including the local ‘water music’ and their passion for religion.

For a more general overview, I recorded an entire podcast on Vanuatu. Give it a listen!

—–

Like this post? Pin it!!

Smol Nambas village visited: 22 July 2018. Cannibal site visited: 27 July 2018.

Trips were booked through Malampa Tourist Board, but I paid for them myself so there!

A question i have often asked myself and one i must ask friends next year when i return to Vanuatu. Are pigs native to the islands or were they introduced.

The suggestion from my research is that the earliest settlers on the islands a millennia or two ago brought them with them. So not ‘native’, but as native as humans are.