I’ve always been interested in history. But history on my own terms, about topics I can relate to, not necessarily what’s been taught in history lessons. I dropped out of University after a year because my degree course (‘Social and Economic History’) seemed to end up combining the worst attributes of two of the subjects at school I was relatively keyed in to (I mean, does anyone outside of University really care about the economic industrialisation of the USA in the 19th Century?!). My interests have always been more geared towards chaos – war, revolution, the collapse of empires and the creation of new states – and all that that brings (hence my near-obsession with dark history. Ancient fossil you say? Looks like a generic piece of stone to me. Oh cool, on this spot 20,000 people were put to death!). Where these interests come from is hard to say, but much of it I think comes from two board games I had in my Primary School days -> ‘Imperium Romanum II’ which played out the rise and fall of the Roman Empire over 500 years, and ‘Kingmaker’ which delved into great detail about what was later known as ‘The Wars Of The Roses’, the conflict in 15th Century England/Wales that produced four Shakespeare Plays (all incredibly biased, btw – Richard III was framed!) and is brought up whenever sporting sides from either side of the Pennines meet.

Overview of Conisbrough Castle ruins.

One place on the Kingmaker map was Conisbrough Castle in South Yorkshire; in the game designated as being a home of the Clifford family, whereas in real life the Cliffords were very closely related to the Yorkist faction and thus during the war the castle was actually directly controlled/owned by King Edward IV. Its earlier history is actually more interesting – being used as a pawn in a domestic dispute (John de Warenne (A) v Thomas Earl of Lancaster (B) -> A: ‘you had sex with my wife so now I want to divorce her’; B: ‘the courts have denied you, hah’, A: ‘you bastard I’m going to kidnap your wife in revenge’, B: ‘suits me, I’ll just take over your castle in return’) … 14th Century Jeremy Kyle being much more interesting!

The main tower at Conisbrough Castle.

There’s not much left of it today – apart from the main tower there’s a couple of walls enclosing what are now grassy mounds – but that’s no different from most ruins; the important thing is to walk in the steps of history. To be fair, what remains is very well explained and detailed – you have to use some imagination but the information boards and interactive/holographic displays are pretty in-depth, as well as being quite accessible. It’s been popular with visitors for a while – although ruinous since at the latest the mid-1600s, it was used as the setting for the novel Ivanhoe by Sir Walter Scott, and so has been the site of tourism since Victorian times

View from the top of the main tower at Conisbrough Castle, overlooking the town.

The real meat of the war however, lie some distance either side of Conisbrough. Some way to the NW, just outside Wakefield, lie the ruins of Sandal Castle. Directly owned by the Dukes of York, this was the home base of Richard, father of later kings Edward IV and Richard III, but also immensely powerful in his own right. One of the inner circle of King Henry VI, it was his manoeuvring and subsequent falling out with the King in the late 1450s that started the whole conflict off.

Ruins of Sandal Castle. This is all that remains of the Great Hall & Great Chamber.

There’s even less left of the this castle than Conisbrough – it is nothing more than a couple of columns of stone scattered around several circles of hill; so little left, in fact, that the site is open to the elements and free to enter and explore – but it’s still possible to get a feel for how suitable a location it is. Out to the West the land falls into a plain that still provides a clear view far into the distance, but while council-estate housing now fills the North vista towards Wakefield (“Duke of York Road” continues the sense of history here), this is where one of the most significant early battles was fought. The Battle of Wakefield in 1460 was one of the first battles in the Wars of the Roses, and was an early victory for the Lancastrian side in the war, and may have given us the mnemonic “Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain” for the colours of the rainbow. In a nutshell, despite occupying the high ground of Sandal Castle, he launched an attack on a much larger force camped at the bottom of the hill. Which completely failed, obviously, and he was killed in the melee. Nobody knows exactly why he did this; theories abound about his miscalculation of his opponent’s forces, his belief that reinforcements would arrive, or that he was provoked into battle by goading from the Lancastrian forces; whatever the truth it was a decisive defeat for the Yorkist cause.

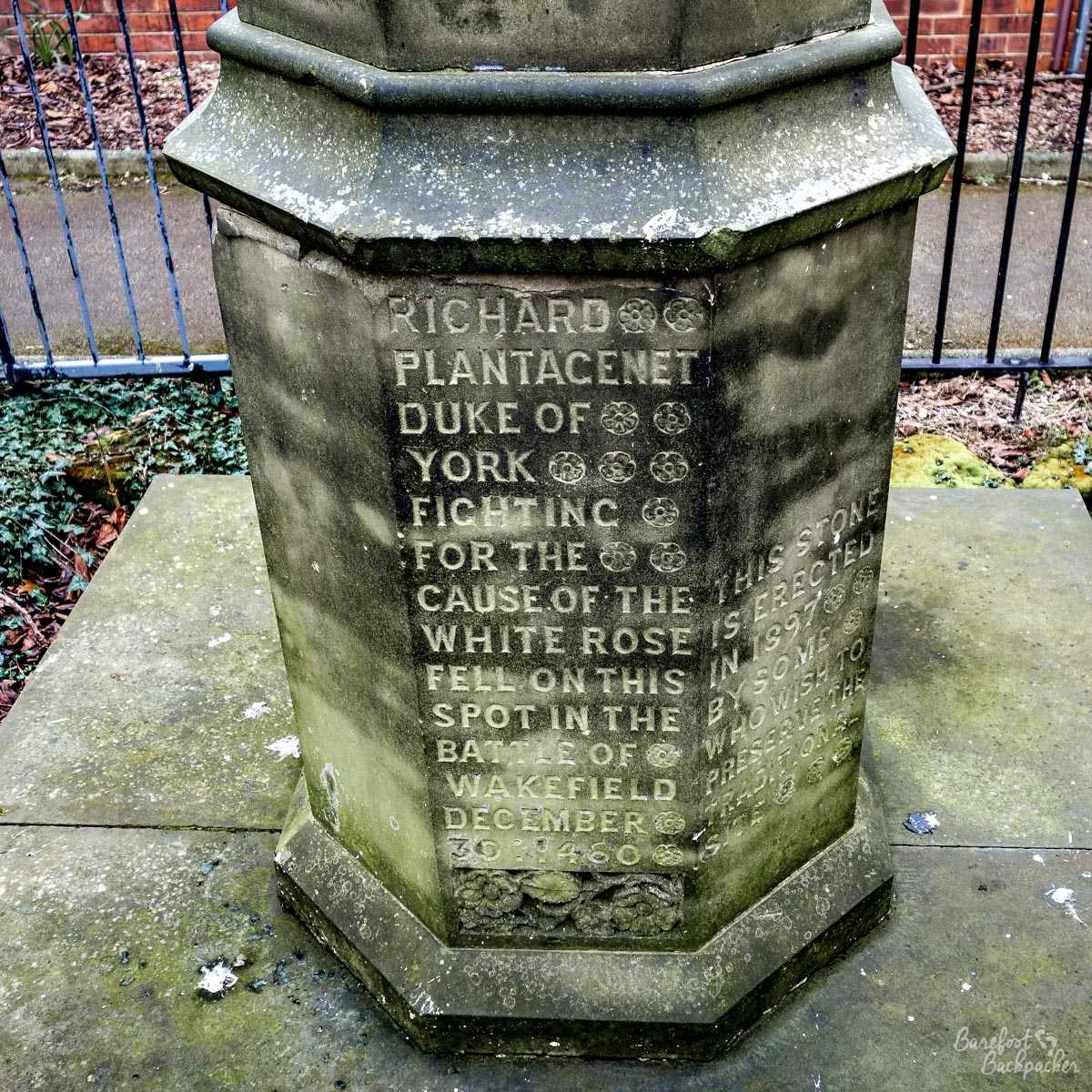

The memorial to Richard Of York, who allegedly died on this spot at the Battle of Wakefield.

Close-up view of the inscription on the memorial.

Despite this setback, the Yorkists proved ascendant for much of the period of the Wars of the Roses. Indeed, the main conflict ended after the Battles of Barnet and Tewkesbury in 1471, the former seeing the death of the main power-broker at the time (Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick – the ‘Kingmaker’ after whom the boardgame was named after), and the latter 3 weeks later where the Lancastrian heir to the throne (Edward, Prince of Wales, son of King Henry VI) died, along with many leading supporters of the King (who himself was executed several days later). The leading Yorkist, King Edward IV, then ruled mostly in peace until his death in 1483. I am aware that this period of history seemed to exclusively contain men who had one of only about three names (Edward. Henry, Richard), but I guess people generally referred to them by title (Richard Neville was generally referred to as ‘Warwick’ for instance). Nicknames, such a ‘man’ thing.

After Edward IV’s death, things got a little ‘messy’. His brother Richard, Duke of York (obviously a different one) took the throne (as Richard III) in preference to Edward’s son (also called Edward), possibly as a protector role as Edward was only 12 at the time – for their own ‘protection’, the younger Edward and his brother (Richard!) were moved into the Tower of London (then a royal residence). And were never seen again; one of the most famous mysteries of the mediaeval age. While most historians and observers have blamed Richard III, his rival to the throne – the Lancastrian Henry (obviously) Beaufort – would have had more to lose while they lived. In truth, it’s most likely the two of them died of illness not long after they were moved.

This, however, coupled with Richard’s habit of falling out with influential nobles, meant that Henry’s challenge wasn’t a mere hope from exile in France. Two years after taking the throne, the two of them faced each other in battle in a field a couple of miles south of the small Leicestershire town of Market Bosworth.

The market square of Market Bosworth. The crests on the wall commemorate the battle.

It was a sunny day towards the end of August (not long after my birthday); although dry and bright, between the two sets of troops was an area of boggy ground that would take a few centuries before it dried out. On one side, atop Ambion Hill, stood the army of Richard III. At the bottom, over the fields, stood the much smaller army of Henry Beaufort, made up in part of French mercenaries. With the higher ground and much larger army, there could only be one winner of this fight, right?

The joker in the pack (and not just because of his non-standard forename) was Thomas Stanley, ‘King of Mann’ and later Earl of Derby, traditionally one of the leading supporters of Richard III … and stepfather of Henry Beaufort. With divided loyalties (and one of his sons held as a hostage by Richard to ensure his support), his fairly substantial force was parked up on one side of the battlefield, watching, waiting.

Memorial of the Battle of Bosworth. A crown on a lance is surrounded by stone seats representing each of the armies involved.

In the event, his force wasn’t needed. Innovative (Roman Army-esque) tactics from Henry’s force, coupled with worry about Stanley’s troupe, forced Richard’s hand and he stormed over the boggy ground straight into Henry’s bodyguard. His horse got stuck and he had to dismount, but still he kept fighting, wielding his sword like a possessed man on a mission. At one point he got close enough to kill Henry’s standard-bearer, but ultimately his battle was, like his dad’s, in vain – Henry’s troupe was too strong and soon overpowered and killed Richard.

This stone commemorates the death of King Richard III, and used to stand on the site he’s believed to have fallen. These days it stands in the main yard of the Bosworth Battlefield visitor centre.

Ever since, there has been much dispute over where the battlefield was. On Ambion Hill, believed for a while to be where much of the battle took place, there is now a museum. Although reasonably small, it’s a good combination of accessible and in-depth – using interactive tales of several of the types of people involved in the battle (including a representation of Thomas Stanley himself), it goes over the background to the battle from both sides, a brief overview of the order of battle itself, and then goes into a bit of detail about the long-term aftermath.

The museum also has a small arena where, on special occasions, they hold mediaeval tourneys and have falconry displays. They also offer guided walks around the general battlefield site – although archaeological research has finally proven that the site of Richard III’s death now lies a mile or so away in a farmer’s private field. It’s only by going to sites like this that you get a scale of just how big a battlefield is – when looking on a plan it feels like it’s only a hundred or so metres between the armies but sometimes it can be much more than that.

There’s a path from the visitor centre that tours part of the battlefield site. It’s lined with exhibits like this, demonstrating some of the weapons/armour used. This is cannon shot, nasty stuff.

Somewhere through there, about 3km in the distance, in a farmer’s private field, is the believed actual spot where King Richard died.

The battle may have changed the course of history. Henry Beaufort (then Henry VII) married Richard’s daughter, uniting the two sides of the war. His son, Henry VIII, had ‘a bit of a spat’ with the pope, founded a new religion, and took England’s first steps on the road to world domination. Richard was far more introspect and insular; had he won the Battle of Bosworth (and the difference could be measured in mere feet), he may have taken England down a far different, less dominating, path, and this blog post may have been written in provincial Spanish.

Of course, there’s always beer…this was in the nearby town of Hinckley, from a Leicestershire brewery. However I don’t seem to have made any notes on it …

It’s weird how small moments are so pivotal.

—

Authorities visited: Wakefield (18 March 2017), Doncaster (11 June 2016), Leicestershire (7 May 2017).

Would love to see those beautiful colors and all that history in person. It’s crazy that such a small number of people wielded so much power even back then. It’s interesting to think that really not too much has changed, but still good to look back and see what once was. Thank you for sharing and for confusing me with all the names. Kidding. Great stuff and loved the read:)

Haha, yes – the difference is in those days it was by landed gentry; these days it’s money and communications. And yes, the names confuse me too! I guess it’s why nicknames are so common (remember we’ve had eight kings called both Edward and Henry in history!). Thank you for reading 🙂

Haha cheers! Yes I don’t think much has changed really; still a small number of people wielding a lot of power (especially true as I write this – what will history make of March 2019 in UK History?!). Yeh, we’ve never had a King Trevor …