Whenever anyone thinks of visiting Chernobyl, what they think of often isn’t the power plant itself. Rather, it’s the pictures and video they’ve seen of the nearby town covered in trees, where weeds and vines have pushed through the cement roads and pretty much swallowed up the concrete of the tower blocks. And the fairground. (It’s always the bloody fairground). In addition, many people may recognise or associate it from playing too much Call Of Duty 4. This is Pripyat, and to be fair it is the most interesting reason to go.

What is the history of Pripyat?

The town itself was founded in early 1970, and there’s a sign on the way in that really leans into this period of typographic style. It’s a huge sculptured rendition of its name in a very 1960s/1970s ‘futuristic’ font – if you look at many posters of the 1960s, especially from the Soviet Bloc, you’ll very much strongly get a sense of this futurism. It looks painfully nostalgic now, as future-setting often does.

The ‘Pripyat’ sign, on the outskirts of the city

Incidentally, there seems to be a small belief Pripyat was built in the days immediately before the explosion, and the town had only just been settled when it was evacuated. This is simply not true. However, what does seem to be true is the iconic fairground, of which more later, hadn’t been officially opened by the time of the explosion – this was scheduled for the May Day celebrations the following Thursday.

Pripyat was built specifically to serve the power plant at Chernobyl, which is only a couple of km away. This was generally the way the Soviets designed places – they saw a need for an industry (in this case, energy), built a factory or other industrial complex to take advantage of that need (in this case, a power plant), then built a town to serve that complex (in this case, Pripyat). The Soviet Union was full of towns and cities like this, places built specifically to harness mining, shipbuilding, space exploration, nuclear warfare, steel-making, pretty much anything which would give them a boost in their rivalry with the West.

Pripyat from above

You *can* visit Pripyat. Though probably only because a) it’s in Ukraine, and b) it blew up.

How many people lived in Pripyat?

The reported population of Pripyat at the time of the explosion was just under 50,000 people. Which makes it about the same size as Dunfermline (Scotland), Durham (England), or the urban area of Midland, Michigan (USA).

Its current population is officially zero.

Is Pripyat safe to visit?

In the sense of ‘is Pripyat still radioactive’, yes it’s safe to visit. Just be aware some things hold radioactivity longer than others, as you’ll read later. Being there isn’t dangerous at all; what’s dangerous is some interactions with the environment. Take precautions, and if in doubt don’t touch anything.

At the time of writing, the biggest danger is Russian/Belarusian attacks.

What does Pripyat look like?

One of the first things you notice about Pripyat and the exclusion zone is that it’s not entirely empty. Animals don’t acknowledge human boundaries unless there’s impenetrable barriers which have completely blocked an area off. For instance, the area around the Pripyat sign is popular with horses, who gambol on the railway line. I don’t know how many trains still use that railway line but they don’t seem to care.

Horses on the other side of the road from the Pripyat sign. We didn’t approach each other

(What used to be) One of the main roads in Pripyat centre

How long until Pripyat falls down?

Pripyat itself was built out of concrete, mainly, and, without maintenance, that tends to have a lifespan of around 100 years. However, there’s a large lack of structural integrity here. There are trees growing through many of the walls and foundations of the buildings. In addition, it’s s in a region that gets cold, snowy winters so ice will form, expand, melt, and crack the concrete still further. It’s thus likely many of the buildings will collapse much sooner. Indeed some of them are already too dangerous to visit inside.

We went in them anyway. But that was nearly ten years ago.

What is Pripyat’s Fairground like?

Out of everywhere in the city, the fairground is the one spot everyone seems to recognise and associate with Pripyat. Especially the Big Wheel. It is just as eerie as you imagine, and I’m kind of surprised the rusted joints haven’t snapped yet. The cabins at the top of the wheel are (were!) above the tree-line, and would have been the best view of the city at the time. The wheel itself definitely looks iconic, stationary yet still clearly identifiable in the trees and the broken cement. The payment kiosk was still present on my visit, though obviously no longer serving any purpose.

Arguably the most famous site in Pripyat

The dodgem cars in Pripyat’s fairground

What are the tower blocks in Pripyat like?

The tower blocks themselves are standard-issue for the time and place, and all generally look the same from outside, The only difference is the height – some only rise to five storeys, while others climb above the trees and reach up to the mid-teens. Inside they’re all much of a muchness. In a way they’re reminiscent of the tenement blocks in Glasgow, although they look substantially different. Fundamentally it’s the same kind of principle – a little basic but pretty comfortable, and all built to the same standard.

A low-rise apartment building in Pripyat

Inside a standard apartment in Pripyat

Now, I said about the potential views from the top of the big wheel. *The* best views of Pripyat are from the top of the large tower blocks where everyone lived. I’m almost certain this isn’t a view that people could have got at the time, nor is it a view I feel you can get any more, because of health & safety reasons.

Looking down at an apartment block in Pripyat

What other buildings can you visit in Pripyat?

A tour of Pripyat will take you to a number of the buildings. My tour could go *in* a few of them, though as I say I don’t know how that would be now as no-one’s doing maintenance of them so they are literally falling down.

As befits a town of its size and importance, Pripyat had many buildings that served the community. One of the first we went to was a large supermarket. As you might expect, the place was quite ruinous and debris-stricken. The aisle shelving was upturned and broken, having been smashed into the concrete floor. Much of the infrastructure was still in place and identifiable, even down to the remnants of the overhead signage, though what it had once said is not something I’d be able to tell you.

Inside the supermarket. I’ve already found the cottage cheese aisle

The hospital and doctor surgery still had health posters and opening times on the wall, and doctor’s ledgers with information written on them, not too faded even after thirty years. The waiting room still had chairs along the walls, empty, waiting in vain for new patients to sit and be checked up for, I don’t know, signs of leukaemia or something. For some reason there was also a rusting bike frame on the floor – maybe one of the last patients had cycled to see a doctor.

As a side note, the group had a couple of Geiger counters, more for ‘oh that’s a big number’ selfies than anything else, but it was in the hospital we made use of them. Some medical clothing had remained – nothing more than a discarded piece of cloth or fabric, but the Geiger counters recorded figures that suggested wearing it for more than five minutes would kill you. Evidently radioactivity stays longer in clothing than the natural environment.

Evidence of radioactivity still exists in some places

I mean, it still has wheels so I suppose you could still use it

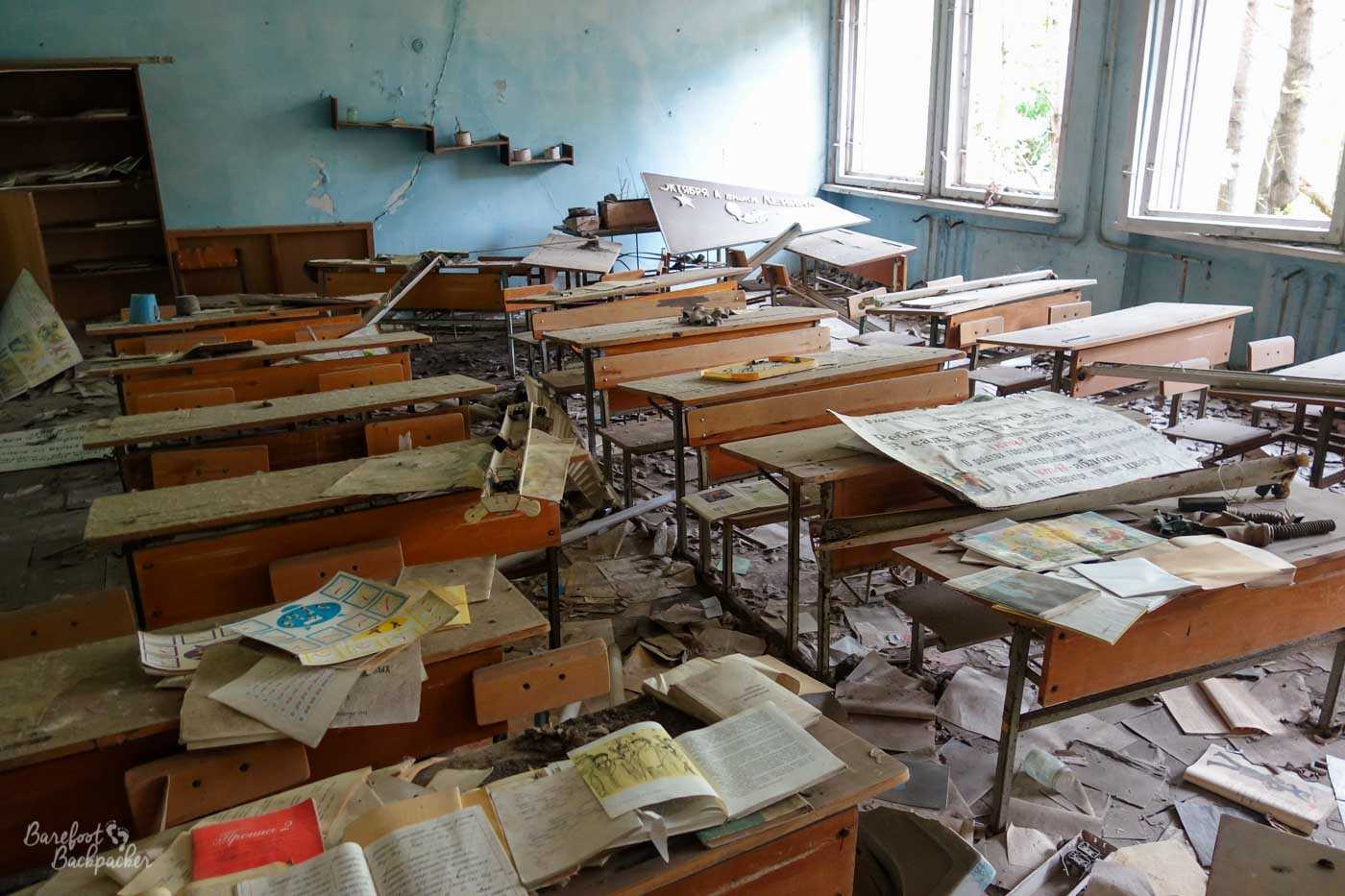

One of the classrooms; you can definitely tell what it used to be

I don’t know what it says though

I don’t know what sport you’d be watching – tree-climbing, maybe?

An empty swimming pool is a very eerie-looking thing

Why is Pripyat derelict?

It is important, very important in fact, to note that although the town is pretty much a decrepit, derelict, demolished hulk, none of the actual damage was done at the time. Indeed most of the residents didn’t even know anything had happened. This wasn’t a Hiroshima-type event causing regional-wide destruction; the vast majority of the danger was through invisible radiation, the fires at the plant never reaching much beyond the reactor itself. Rather, the look and feel of the town is caused mostly by the effects of nature reclaiming a town having been abandoned, and a little bit by ongoing looting in the years afterwards. Remember that most of the townspeople left their possessions behind as their evacuation was meant to be temporary, so a good chunk of people’s stuff was effectively left in unguarded, empty, properties.

So the reason there’s very few items of value or use in the town and every building is empty is because in the years after the explosion, people nicked it all.