- On my visit to Chernobyl and Pripyat, one of the places I was taken to was a site known as Chernobyl-2, Back in the 80s it was labelled on the maps and the signposts as a Children’s’ Home. It’s 11km outside Pripyat in a straight line, and down a 7km-ish road through the trees off the main road between Pripyat and Chernobyl City. It’s deep in a forest, almost as if they wanted to hide the fact that it wasn’t really a Children’s Home.

The Duga Array, the Russian Woodpecker, as seen from ground level and close up

What was the Duga array?

It was never officially revealed at the time what this huge hunk of metal in the forest actually was, although it’s clearly not populated by small people. However most people in the West at the time believed it was an over-the-horizon radar array, and this has since been confirmed by the release of Soviet-era documentation.

My knowledge of physics isn’t great, it was never a subject I found interesting. As such, I’d suggest doing your own research on what over-the-horizon radar is, and how it works. As far as I can gather though, radar involves firing radio waves into the sky, and if they bounce back, well, you’ve found yourself an object. Normal radio waves though travel in straight lines, which means since the Earth is curved, you can only detect something in your line-of-sight, otherwise the wave carries in a straight line into the atmosphere and away. An Over-the-Horizon radar is one that uses simple physics to ‘bounce’ the radio waves off the sky, thus allowing them to travel much further around the Earth. Doing this effectively requires large computing power and even larger transmitters and receivers, located close to but still some distance from each other.

The Duga Array, as seen from behind

Its location here was twofold. It was in a relatively remote area of the Western Soviet Union, close to The West, and surrounded by trees. This makes it a perfect spot for both remaining hidden and yet be easily used for tracking what the enemy was doing. However it was purposely constructed close to the Chernobyl Power Plant. The two came as an item, in a sense, because it’s believed about a third of the entire output of the power plant was used by the array. Tracking foreign objects on this scale used a lot of power.

Why was it called ‘The Russian Woodpecker’?

The best frequencies for over-the-horizon radar seem to be in the low MHz range, in what’s commonly known as ‘shortwave radio’, similar to those used by amateur and CB radio, and air traffic control. The Duga array’s power output was estimated at around 10 MW.

This meant the pulses sent out by the Duga array were picked up as transmissions on radio sets. What it sounded like was a constant and repetitive ‘buzz’, at regular intervals (several times a second), similar to how a woodpecker would sound, hence the name. The problem was the signal was strong enough to ‘leak’ over several frequencies and affect other broadcasts, making that wavelength range virtually unusable, to the extent people manufactured ‘woodpecker-proof’ radio systems. Note this affected the Soviets in the same way as the West, and at some point it changed frequencies without warning.

The Duga Array, as seen from directly below

I find all that kind of thing fascinating; mysterious radio noise and the like. Especially because something like that was so … ‘illicit’ growing up – I never thought I’d get a chance to see something so intrinsic to the enemy’s military.

How big was the Russian Woodpecker?

Well, you can actually see it, on the horizon, from the top of the tower blocks in Pripyat. As secret sites go, it’s not exactly perfect, especially as back in the day I’d imagine there was less forest cover.

The Duga Array, as seen from the top of a tower block in Pripyat

– “Comrade, that’s a children’s home”

– “It … clearly isn’t”

– “Are you saying the Party lies? Off to Siberia with you”

It’s about 700 metres long and 150 metres high. It’s not something you can just sweep under the arboreal carpet.

What was it like to visit the Russian Woodpecker?

The site itself is quite well protected. The road to it ends at two sets of huge gates, each embossed with a metallic 5-pointed star of the kind of so beloved of communist aesthetic. One set of gates is very much suffering in the years since abandonment, the other is still quite solid.

The main entrance to the Duga Array

Inside the buildings are long, wide, corridors, some of which have had floor collapses so you have to walk along the supports/foundations. The walls are, like everywhere else, pretty damaged with bits falling off everywhere. There’s not much light in these buildings as the windows are quite small and often quite distant. The roof seems to be falling down, or at least the insulation is falling through the metallic beams holding it all up. I obviously can’t help but wonder about the presence of Asbestos, but one assumes if it were present in dangerous levels, they wouldn’t let us in here in the first place. Right?

Broken keyboard in the nerve centre

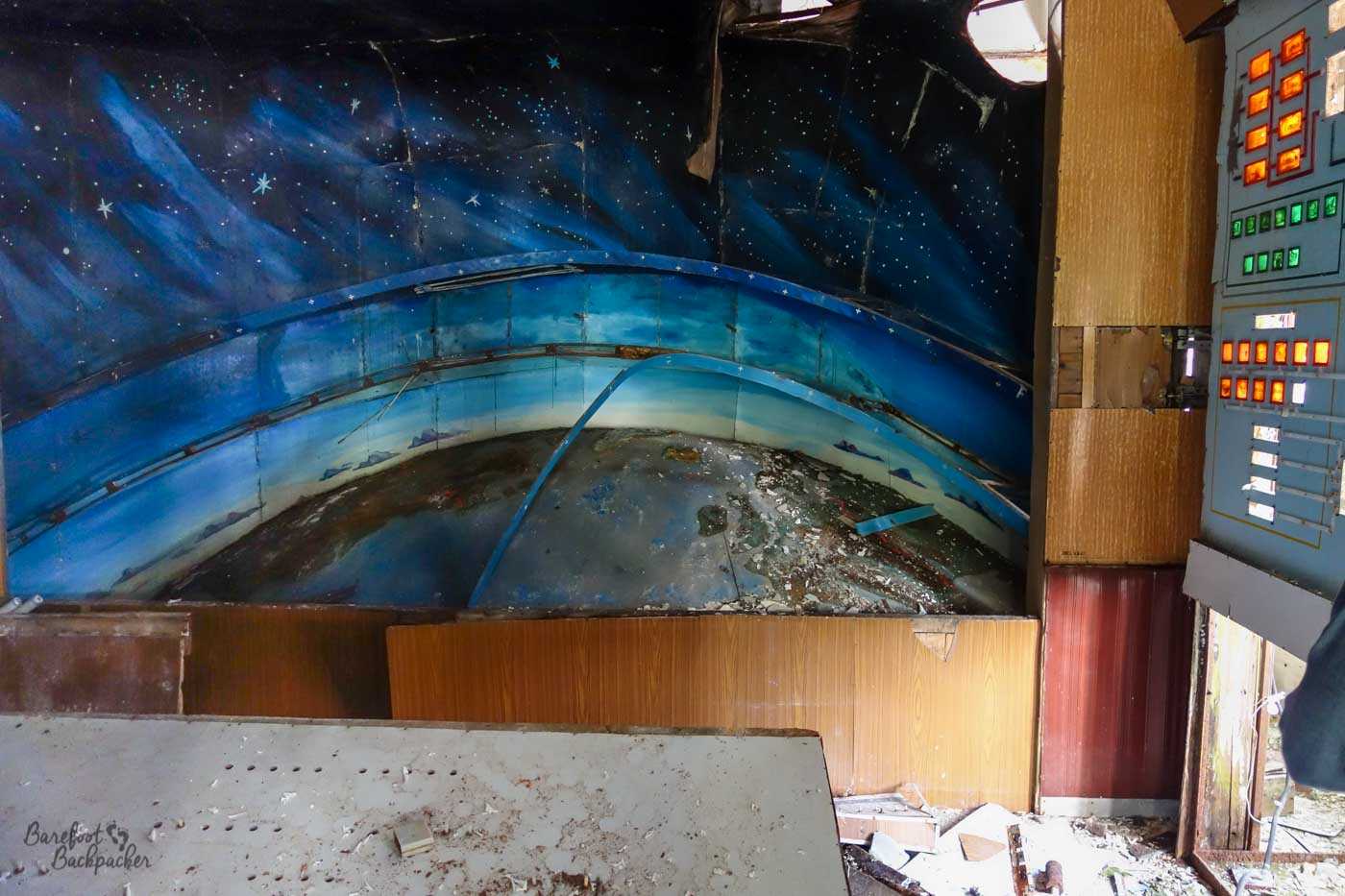

Some kind of console I guess?

The main control room of the Duga Array

You can see where they were interested in, for sure

There’s almost certainly a whole host of secrets still unrevealed. And maybe that adds to the feelings of adventure.