I was born in Year Zero.

To be absolutely precise, I was born a few months *after* the Khmer Rouge victoriously entered Phnom Penh and took power on April 17 1975, but they designated 1975 as ‘Year Zero’, and, effectively, tried to restart history. I was too young to remember anything about the Khmer Rouge (I have vague recollections of the subsequent ‘Save Kampuchea’ charity campaign after they were overthrown), but, whereas people who lived through the Nazis or Stalin are slowly dying out, the Khmer Rouge reign is still well within “living memory”.

Background and Rise of Pol Pot

It’s hard to express exactly what happened with sheer words. The concept was actually pretty simple: a well-connected and relatively affluent Cambodian called Saloth Sar (later to call himself ‘Pol Pot’, though no-one knows why) was educated in France, and while at University there he was, perhaps inevitably, influenced by the radical left. Upon a later trip to China, he was incredibly impressed with the concepts of the Cultural Revolution, and tried to imagine how that would work in his home country. When he visited the very rural East of Cambodia, with peasant farmers, he decided the ideal future for Cambodia was as a purely self-dependent, agrarian society, with no need for money, hierarchies, or education, as everybody would be fully employed working on the land for the benefit of the state.

From the mid-late 1960s, he led a nominally-Communist armed militant movement that fought to overthrow the government in the Cambodian Civil War, inextricably linked to the Vietnam War happening just over the border, as well as to similar conflicts in Laos. His forces, dubbed ‘Khmer Rouge’ (Red Cambodians) by King Norodom Sihanouk, seemed to have a fractious relationship with the similarly pseudo-communist forces of North Vietnam, but by the middle of the 1970s, both forces had won with a little help from each other.

Now, given a gradual long-lasting series of re-education plans, organised logistics, and the will of the people, he might well have done rather better. Indeed the Cambodian people saw his takeover as a celebration of the both the end of bloody civil strife and French/American imperialism and colonialism. However, his simple plan was simply executed: upon finally gaining control of Cambodia, within *48 hours* he had closed all the hospitals, all the schools, all the monasteries, and evacuated all the cities, transporting *everyone* to work on the land. He declared this to be the start of a new Cambodia – ‘Democratic Kampuchea’ – and from here on, he declared that Year Zero had begun.

‘Year Zero’ and the Regime In Action

In essence, ‘Year Zero’ was a very plain and far from complex idea. It was, literally, going ‘back to basics’ – as a species we came from the land, and industrialisation had blinded us to that fact, and made society rampant with inequality. Under Agrarian Communism, everybody would be equal, with equal rights to work and own the land, and everyone would grow and farm enough so everyone could live equally. To be precise, “zero for him, zero for you – that is communism” – everyone was the state, and the state therefore owned everything. Yes. Not quite anarcho-primitivism, but possibly not much better.

You might well want to examine just how bad this bad plan was actioned. Take a bunch of city-dwellers who’d never handled so much as a hoe in their lives and get them to work on the land to produce excessive amounts of food, for effectively no wages and with little training. Added to this there was no treatment for disease except local remedies, and that the people already *in* the countryside didn’t much like or trust these ‘New People’ from coming in where they were, effectively, not wanted. In addition, working conditions were, uhm, ‘basic’ – work over 12 hours a day doing very physical work, with only a couple of bowls of gruel/rice-based watery stuff a day.

People were separated from their family. The Khmer Rouge theory was that *they* (the state, the party, the country) were the only family you needed. At first people were sent back to their ‘home’ villages, but over time people were moved about the country wherever the government deemed they were needed. Men were kept with other men, women with other women. Children were, more often than not, recruited to be the ‘soldiers’ (as the Khmer Rouge knew that children were much more easily ‘moulded’ to a certain viewpoint without asking the necessary questions). After the Khmer Rouge fell, there are millions of tales of families moving back across the country to try to find their loved ones, often to discover they weren’t going to be coming back at all.

And then of course there was the fear. Fear of being arrested, fear of being shot, for the smallest of offences. One woman was killed on the spot for being accused of stealing two plantains, which she’d claimed had been given to her by a guard. Who denied all knowledge, of course. Every weakness was eradicated. There was a regime of terror.

Some people didn’t even get that far. In the hours after taking power, the Khmer Rouge eradicated pretty much the entire administrative body that had preceded it. Anyone who had worked for the previous regime, anyone related to someone that had, even friends, were systematically killed. Then they purged on the elites and the intelligentsia. Anyone who spoke a foreign language, anyone who had a degree education, anyone who wore glasses, anyone who had soft hands – a sign that they didn’t work on the land – was taken away and killed. No quarter given. Given most of the leaders of the regime had been educated to university level in France, this is quite stereotypically hypocritical. Or, also, ‘no-one will replace us’.

Overall, estimates of between 1 and 3 million people died in the 3 years, 8 months, and 20 days of the Khmer Rouge regime, either directly (by being killed) or indirectly (by dying of starvation, overwork, or disease). The population of Cambodia at the start was only about 7-8 million. So, at a rough middle estimate, some 20% of the entire population died.

If it happened now, I can pretty much guarantee that everybody reading this will be dead within two days.

Today, one can visit the two most famous and main sites of the murderous regime – the notorious Tuol Sleng prison and the Killing Fields of Choeung Ek. Both are detailed complexes that pull no punches about what they are. Note that there were hundreds of both prisons and killing fields scattered across Cambodia; these however were the biggest and most important of each.

Tuol Sleng Prison

Originally a 1960s-built High School (and it shows, it’s an ugly series of buildings), the Khmer Rouge turned Tuol Sleng (“Hill of the Poisonous Trees”) into the most notorious of their prisons – S-21.

The entrance to Tuol Sleng

The overall structure has been preserved – three blocks of three levels each, built around a wide rectangular open area that’s now been turned into a garden, but presumably would originally have been the playground. One of the blocks still has the rooms set out the way they were found when the Vietnamese arrived – with bare metal-framed beds in large empty rooms – but there are photographs on the wall taken at the time of the (dead) victims they found therein. Another of the blocks was converted by the Khmer Rouge into narrow cramped cells, some wooden, some brick, and these have also been left in situ – complete with remains of metal chains used to lock prisoners in place.

One of the beds in Tuol Sleng that a prisoner would be chained to

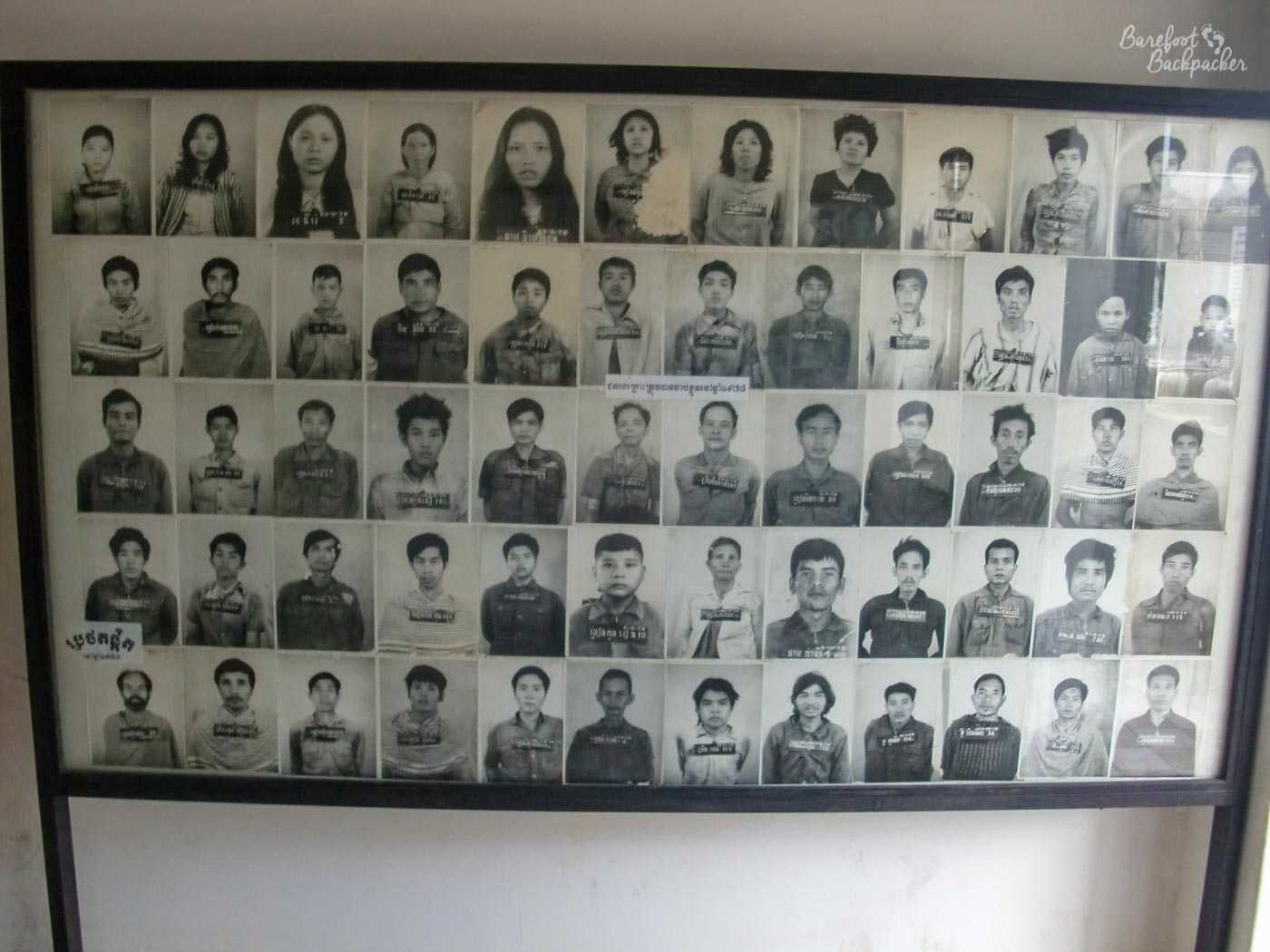

Other rooms now have exhibits and photographs of all the people known to have been processed here. The Khmer Rouge were, like most dictatorships, very anal about processing and leaving traceable records. It’s quite common for Cambodians to go on a visit there and see photographs of long-lost relatives, who disappeared without trace.

Sixty people who were tortured and killed here. A very small proportion.

Torture methods ranged from waterboarding to sleep deprivation, from isolation to removing fingernails and toenails. The day lasted for as long as necessary, and the guards were as terrified as the prisoners (for fear that they’d be next in line if they did something wrong). The idea was to get a confession out of the prisoner – it didn’t actually matter what for – so many people just said the first ludicrous thing they thought of (being in the pay of the CIA was quite a common one). Once the confession was signed, they were generally carted off to Choeung Ek, and anyone mentioned in the confession would then be ‘called in for questioning’. And if that sounds a bit ‘far-reaching’, note that one of the slogans of the Khmer Rouge was said to be “Better to kill an innocent by mistake than to spare an enemy by mistake.”

The old playground. Coffins represent those who died. The wooden frame acted as a gallows, and as somewhere to hang people upside down with their heads in the buckets, which were not filled with water.

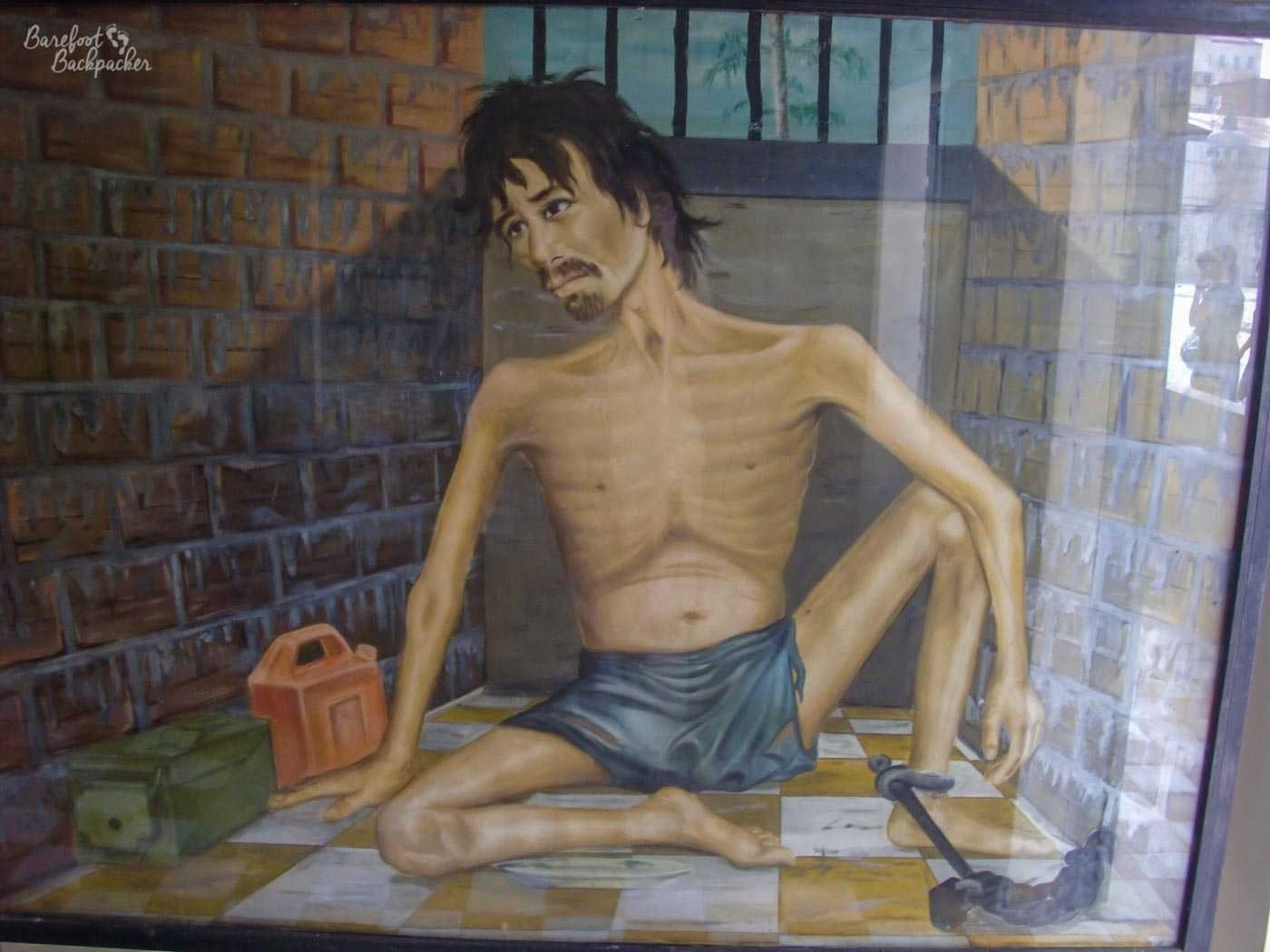

Not many people survived Tuol Sleng. Over the entire history of the site, only about 200 people are believed to have emerged alive, from a total of around 17,000 people imprisoned there – when the Vietnamese came, there were between 7 and 12 prisoners alive in the entire complex. Everyone else held there had been quickly tortured to death before the Khmer Rouge fled. Generally, those that had survived had done so because of their skills – a couple were painters, and one was an engineer so had fixed things in the prison. One of the painters was invited back not long afterwards and asked to paint scenes he’d seen, to show the world what had happened here. If you’re wondering why he agreed, it’s because everyone in that prison made a pact with each other to tell the world, no matter how heart-rendering it would be; they vowed that they would not die in silence or in vain.

One of the milder paintings in Tuol Sleng. The others are far, far, more graphic.

The walls are covered in these paintings, some of which are incredibly graphic, as well as photographs taken by the Vietnamese of what they found left behind, which included a number of people dead or dying in mid-torture. It’s … detailed and to-the-point; possibly *too* much even, but maybe it should be that way.

The Killing Fields

If Tuol Sleng was where they tortured people before killing them. Choeung Ek was where they, well, simply killed people.

The entrance gate to Choeung Ek – The Killing Fields.

The area known as Choeung Ek – a phrase that Google Translate suggests means ‘Champion’ – is about 15km SW of the city and, at the time, would have been ‘quite a long way’ outside the city proper (these days it’s pretty much in the suburbs). Originally a Chinese burial ground (and there are still scattered remains of Chinese gravestones, mostly long since destroyed), it was turned into a very organised and processed site of mass execution.

Remains of one of the Chinese graves that existed before the Khmer Rouge took over the site.

Prisoners were loaded onto trucks more-or-less at dusk from Tuol Sleng Prison and taken, bound and blindfolded, to the site. Mostly they were told they were being transferred to a ‘new house’ but is likely some of them were well resigned to their fate. There then followed a simple checklist of processing each prisoner individually (to make sure none had escaped), then getting them to kneel down while one of the guards hit them over the head with an implement originally used for farming, or in some cases, slit their throat with a palm tree branch.

One of the many mass grave sites identified on the site.

Generally, the Khmer Rouge didn’t just kill one person, they killed the entire family. This included babes; their theory being “to get rid of the grass you have to get rid of the roots” – leaving no-one behind who could take revenge. The method used was often to hold the baby by the ankle and swing it around, bashing its head against a tree until it died. You may not want to know there was a tree designated for this specific purpose.

The tree against which prison guards hurled babies and children.

Another tree in the complex was utilised for a different maleficent purpose; they hung loudspeakers on it and broadcast Khmer folk music incredibly loudly, 24 hours a day. This had two effects; it ensured those arriving would be subjected to a kind of sensory overload, but mainly it was to hide the screams and the sounds of execution from the outside world.

The tree on which guards hung speakers.

You didn’t have to have *done* anything to be arrested either, they just had to *think* something, or even just not like you. Party members were especially pounced on (to preserve the integrity of the revolution) – a bit like Stalin before them, the Central Committee of what they called ‘Angkar’ (‘The Organisation’ – a front for the Cambodian Communist Party) were somewhat paranoid – one of the mass graves at Choeung Ek was found to contain 166 headless bodies, all of whom were dressed in the uniform of the Khmer Rouge. It seems these were soldiers who were killed in a purge of Eastern Cambodia of ‘undesirable elements within the revolution’ – this included the head of the entire Eastern Zone of the country, as it was believed he was in league with the Vietnamese and courting a possible invasion. Although both ‘communist’, Vietnam was Soviet-backed while Cambodia was much more aligned with China.

When Choeung Ek was abandoned, everything had been left as it was, with blood on the trees, bones everywhere, pieces of clothing torn and flapping in the breeze. It must have been quite an appalling sight. Even today you can still come across the occasional piece of bone or clothing fabric that has recently come to the surface due to weather churning up the ground.

Fragments of clothing fabric dug up soon after liberation.

Most of the bones have been now properly handled according to Buddhist tradition, which, combined with preserving the memory, means that a Buddhist tower has been constructed in the site with 17 levels, each level containing bones of varying types and ages – the lower levels have the skulls whilst the higher levels have the other bones and bone fragments, all sorted by age, sex, and type.

One shelf of skulls in the stupa – there are many – this one laden with those of teenage girl victims.

The End Of The Regime

In place for nearly four years, the Khmer Rouge’s regime collapsed quite suddenly. On 25 December 1978, the Vietnamese did finally enter the country with some force. They were met with pretty much no resistance, even when they rolled into the capital Phnom Penh, mainly due to the entire Khmer Rouge policy of emptying the city and forcing people to work on the land. Imagine a Scottish or (heaven forbid) a French tank driving up a completely empty Oxford Street in London, because everyone had been moved away to work on the fields in Norfolk. Eerie.

They were also helped by the border is only about 200km to the East, and having a lot of underground support in that frontier zone. Although the government knew the Vietnamese were close, they didn’t tell their officers quite how close, which meant both Choeung Ek and Tuol Sleng were abandoned incredibly quickly, with very little time to, shall we say, clear up the admin.

Whether the Vietnamese action was an invasion or a liberation depends on who you ask. Khmer people would say liberated. The USA, UK, Australia, Thailand, and China say ‘invaded’ which is why we in the West gave diplomatic recognition for the Khmer Rouge for a further 10 years, because better a genocidal maniac than a Soviet, I guess. It wasn’t until the fall of the Soviet Union that legitimacy was given to a new government, but rebels loyal to Pol Pot and the regime were still fighting as late as 1999. Pol Pot himself died in 1998 in arguably suspicious circumstances, having been ‘overthrown’ by other leading Khmer Rouge members and placed under house arrest.

Photos of the Khmer Rouge leaders in Tuol Sleng. They are not liked.

In Tuol Sleng are some photographs of the leaders of the Khmer Rouge. People over time have come along and scratched their faces off, and written expletives in Khmer over the top of some of the photographs. It’s interesting to contrast with the north of the country; in the border town of Anlong Veng is the burial site of Pol Pot, and locals go there to cast offerings and hope it brings them luck in life and love.

Pol Pot’s cremation and burial site, at Anlong Veng, in the far north of Cambodia. It’s definitely not as defiled as you might expect from a genocidal dictator.

One of the issues with regard to the Khmer Rouge regime is the question of the exact word that should be used to describe it. Genocide isn’t technically accurate since, although ethnic groups were targeted (mainly the Chinese and especially the Vietnamese), native ethnic groups within Cambodia itself seemed to do rather well out of the regime. In addition, people seem to have not been killed because they were *ethnically* foreign, more because they were *actually* foreign. In any case, most people who were killed were ethnically Khmer – Auto-genocide has been used for this but it is an awkward term. It’s also not a War Crime since, regardless of the ongoing Cambodia-Vietnam conflicts of the late 70s, the deaths themselves did not take place under a state of war. One *could* theoretically use the term Holocaust as the word has been used to describe several major massacres over history, and simply means ‘whole (ie all of it) burnt’, but that word of course has specific connotations these days. Possibly ‘Omnicide’, if such a word exists.

One interesting comparison to be made between Democratic Kampuchea and many other totalitarian dictatorships is the fact that, with regard to orders and processes, ‘Angkar’ was top-heavy; that is, the leadership made orders and everyone followed. Stalin similarly was very good at this; if he wanted you dead, you died. Nazi Germany was pretty much the opposite; a *suggestion* from Hitler or Hess became a *recommendation* from the party which became an *order* from the middle-ranking officers/middle-management, who wanted things ‘done’ in order to further their career – in much the same way that many businesses (especially Call Centres) work these days, although obviously the Nazis were much more organised. Conversely, career development seemed to not be an option in Democratic Kampuchea; if you were young you were taken on as a soldier or a guard, otherwise you worked in the fields. That, or death, were your only options.

Conclusion

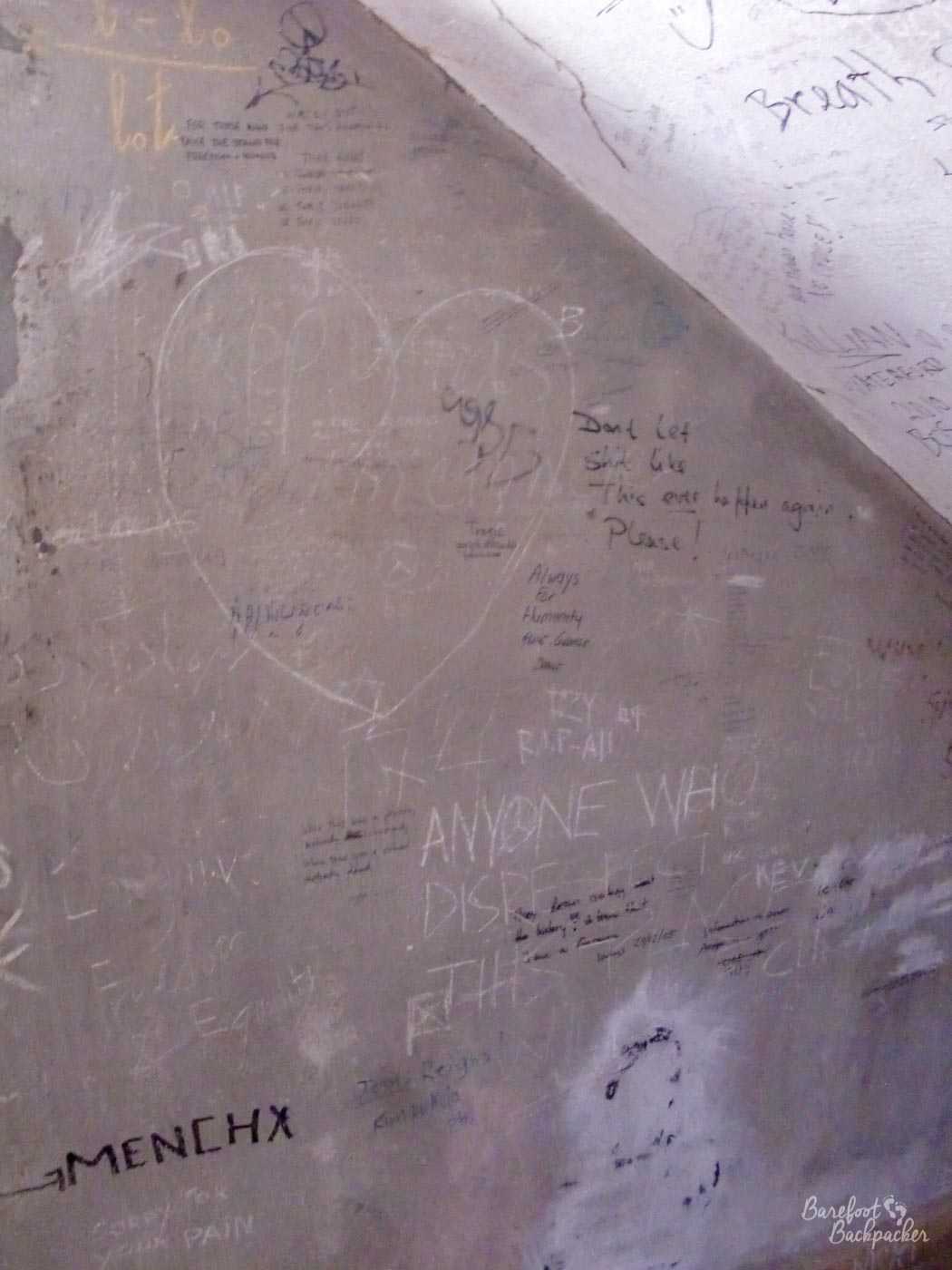

After every conflict, every human disaster, after every genocide, people say ‘how could this happen?’, and ‘Never Again’. Indeed such sentiments are written on a wall of Tuol Sleng specifically indicated for this purpose. And yet it does, time after time. I may have been born in Year Zero, but for my friends, their equivalent Year Zero coincides with Bangladesh, Guatemala, Rwanda, Bosnia, Timor-Leste …

Comments written on a wall by locals and tourists at Tuol Sleng.

It’s important to know these things, to get a sense of how and why they happen, even if we’re powerless to prevent it. I’d love to finish on a more optimistic note, but I can’t.

Tuol Sleng and Choeung Ek provided two of the most emotional travel experiences in my life. You written about them and the history well. Well done.

Thank you. I try to be … factual rather than emotive, but it’s a hard topic to write about.

It’s always good to read about Cambodia. I *know* how bad it was, but the West doesn’t talk about it nearly enough.

Yeh, I think it’s because ‘it happened a long away away’ and ‘we weren’t involved’, so we’ve tended to play it down and not talk about it much. It surprises people when I point out that, proportionately, the Pol Pot regime killed more of the population than Hitler’s.