The heat hit me as soon as I stepped off the plane. Tentatively hopping across the airport tarmac like someone walking over hot coals, the quiet shade of the terminal building provided but a brief respite from what was to come. If anything it felt even hotter coming out the other side, and a US$8 taxi ride I quickly decided was preferable to a 6km walk to the hostel. Any ambitions I may have had to journey predominantly barefoot through Southern Africa, like I had in West Africa, had evaporated after the first two minutes.

I mean, when I could, I did, obviously. This was at the railway station in nearby Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, on about day 4 of the trip.

I’d left England in the middle of a mild, if unusually wet, early Winter; I’d been used to unseasonably placid temperatures around 11°C; however the forces of nature (a particularly strong El Niño) responsible for bringing flooding to the North-West were the same as those marking my time in Southern Africa with equally unseasonable weather – although my trip coincided with early onset of the ‘wet’ season, no rain had been seen here for several months, and temperatures had been in the mid-to-high 30s°C for some time, causing even the locals to express discomfort. This was to be a feature of my entire journey through Southern Africa, not just in Zambia but even as late and far South as Lesotho.

Apart from the unexpected and oppressive heat, the town didn’t give me too bad a first impression. Although it had ‘suburbs’, pretty much everything you want or need was on the main street, which stretched for over 3km from North to South – a more-or-less straight dual carriageway with only one bend; a sharp turn outside the Livingstone Museum. Most of the road was lined with shops and offices; stone buildings rather than makeshift stalls, although many had definitely seen better days and lacked TLC. I’m not sure if it’s just my mental association, but I felt some of the architecture reminded me of the stereotypical American Wild West; it would be easy to imagine a drunken gunfight taking place across the main street. At the South end of the town there’s even an overgrown railway complete with ‘luxury’ coaches that one could imagine occupied by affluent ladies & gentlemen in foppish hats whilst a steam engine complete with pilot (cow catcher) plods along at 20 miles an hour. Damsel in distress tied to the tracks purely optional, and I wasn’t going to try that one (the disadvantages of solo travel :p).

Some of the shops in Livingstone’s town centre. Look, it felt ‘wild west /saloon-like’ to me!

It’s sometimes difficult not to make comparisons with other places, especially ones so far away that their only common denominator is that they share a continent, but I was always subconsciously checking the differences between here and places in West Africa; it was something I did throughout my trip. I don’t know if Livingstone is representative of Zambia as a whole – I suspect that because of the tourist influx, it is not – but I found the town to be much ‘calmer’ than similar towns in Ghana & Benin, with surprisingly few hawkers trying to grab your attention. There is a ‘touristy market’ on the main street where young pasty-white people with small daypacks, knee-length shorts, and straw hats mull over purchasing unique locally crafted ornaments for twice as much money as they would be the same as in the next town along, but for a tourist town, I found it to be very chilled, almost soporific.

Apart from the falls themselves (some 10km down the main road), one of Livingstone’s main attractions was the museum. It was quite a nice way to spend a couple of hours out of the mid-daytime heat – and I prefer museums that have a local bent rather than just being generic ‘here’s an Egyptian Mummy / here’s some pottery shards from Mesopotamia’. It pretty much covered the history of the Zambia region, from the earliest tribal hunter/gatherers all the way up to Kenneth Kaunda and touching on the problems Zambia had in the 80s where most of the countries it borders were … ‘troubled’.

Obviously there was also a bit on Dr David Livingstone himself – after whom the town is named, and one of a long line of Victorian-era explorers on whom history may not reflect entirely honourably, although nowhere near as ‘divisive’ in modern-day socio-politics as Cecil Rhodes further South. In brief, he was ostensibly a Christian Missionary, passing on “The Good News” to “Darkest Africa”; this was, however, often a front for something a bit more down-to-Earth – he acted effectively as a colonial representative for the British Government, his ‘mission’ to try to convince the local tribes that they wanted / needed British trade / “protection”, ultimately to further British interests in the region partly to expand the empire but, in the short term, to prevent the Portuguese from doing the same thing first from their bases on the Mozambique coast …

The coat worn by Dr David Livingstone while exploring the area. Now, I know I arrived in one of the hottest Decembers on record in Zambia, but even back in the mid-1800s, I refuse to believe he was anything but roasted alive if he really wore that on his travels.

Not far South of Livingstone, quite near Victoria Falls, is the village of Mukuni. Where the road off to Mukuni joins the main road to the Falls is “The Big Baobab”. Baobabs in general are amongst the largest trees in Africa, and this particular one is big enough to climb up – there’s a ladder fixed in place now that leads to a natural ‘hollow’ around halfway up the trunk.

Dr Livingstone is believed to have been the first ‘white man’ to have seen Victoria Falls. The story goes that he was looking for somewhere to replenish his supplies, and climbed this tree to get a good overview of the local landscape. In the distance he saw smoke rising, and headed East to the village. The chief of Mukuni was so concerned at Livingstone’s arrival and appearance that he refused to meet with him until Livingstone could prove that he wasn’t some kind of God come down to wreak vengeance on the village. I’m not quite sure how you prove you’re not a God– to be honest I’m sure I could probably do it every day if asked – but after a couple of hours the chief was convinced.

The Baobab Tree, as climbed by Livingstone. Apparently it’s been here for over 2,000 years.

View from the top of the Baobab Tree, looking towards the spray from Victoria Falls. Presumably in Livingstone’s day, the trees wouldn’t be quite as tall and he’d have had a better view …

These days, Mukuni is no stranger to Western tourists. It was one of the many trips on offer from my hostel (and, to be honest, from pretty much every ho(s)tel in the Livingstone area); unfortunately I didn’t get to see the chief myself on my visit, but I did see the outside of his two palaces (one for him personally, one serving more as a ‘reception area’).

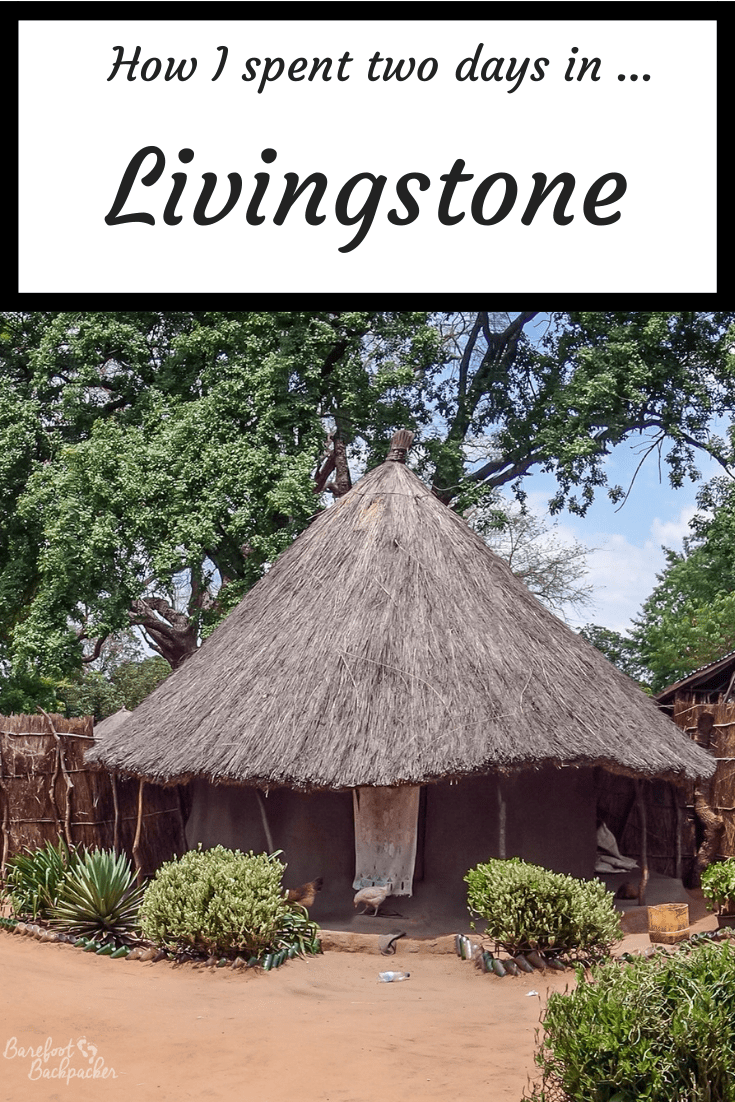

The main housing in the village, which was pretty typical for the area, was in large rondavels – circular buildings primarily made of mud/dung, baked solid and thus resistant to the intolerant sun, topped with a thatched roof. Other things being equal, the roofs would need to be reworked/replaced roughly every 20 years. The other slightly odd aspect about them was they have no windows; any smoke and heat from internal fires escapes via a door lintel. As to why they have no windows, mainly it’s far easier and cheaper to build a rondavel without one; in addition, being an enclosed shady space means the inside of them is pretty cool, while a window would let in the heat from the sun.

The layout of the houses was also unusual, by Western styles. Whereas in the average British residence, there’s one building with several rooms and often a small garden, here there tended to be several one-room rondavels separated by open space. For large families, this effectively means that each generation and/or gender gets their own rondavel to sleep in, with one further rondavel used as the kitchen / dining area. If the family has enough spare land, then they’ll build a new rondavel if their family has expanded.

Inside a family home in Mukuni. You can see the framework in the one on the left; it’s being built/repaired.

Water in the village was provided from a couple of wells, but mainly from several huge water tanks on the edge of the village. Relative to the population of the village though, they didn’t hold that much and needed to be refilled by tanker every couple of weeks. Waste disposal was a simple affair – dig a hole in the ground. When the hole is full, cover and dig somewhere else. It did make the village seem a little ‘dirty’ but to be fair there wasn’t much litter on the ground in general.

The main industry here is agriculture, or at least it had been until recently. Delayed rains and smaller harvests over the past few years has made farming more difficult, and these days the village tends to get much of its money from tourism. The ho(s)tels offer trips out, and some of the money tourists pay for these trips gets fed back into the village. In addition, the village market tends to sell more of the ‘ethnic craft’ tat that tourists so love, rather than everyday products and local trading. To be fair, I did need a hat and it was cheaper than getting the same one from Livingstone …

I asked my guide about the effects of tourism. I expressed a concern that the village would just become a kind of ‘show’ for tourists rather than a real-life village. He said that while, ideally, agriculture would remain the mainstay of their livelihood, they were realistic enough to recognise the value of tourism; the way he saw it, this way not only do they remain in control of what tourists ‘see’, but also it means they can show to these tourists how the village works, so people like me can go back home and tell everyone what life is like here – a kind of ‘education’ in African life for the wider world.

Livingstone was not the city I’d initially intended to start my journey in. The reason I was here at all was to visit Victoria Falls, and my original plan had been to view them from the Zimbabwean side, and stay in the town of the same name. However it appeared that there was some kind of New Year Festival on, so there was only limited accommodation; in addition, booking transport there was tricky and involved awkward flight routing. Livingstone, 10km from the falls on the Zambian side, was cheaper and much easier to get to – a simple change of flights in Nairobi airport.

As an aside, Nairobi airport is not the largest or most interesting airport in which to spend six hours. There’s pretty much nothing there – barely even enough seating, never mind any shops or restaurants, and the décor is a predominantly generically-depressing orange/beige effect. Still, the flight from there to Livingstone was quite relaxed, relatively empty, and passed close by Mount Kilimanjaro – probably the nearest I’ll ever get to it.

Passing close to Mount Kilimanjaro on the plane from Nairobi.

For the record, I pretty much ignored New Year. I was going to be having an early start (6am ish) on New Year’s Day to see some wildlife so went to bed long before midnight. I was still awake to hear the distant fireworks from the town centre, but there didn’t seem to be any activity around the hostel itself.

—–

Like this post? Pin it!!

Visited: 30 December 2015 to 2 January 2016

I remember that museum in Livingstone. I bought a spear there that now lives in my bedroom. This was back in the day was it was perfectly acceptable to carry a spear through an airport.